Tiny Bird

The urge to be a tiny bird

upon a tiny limb, maybe

a bridled titmouse

standing on its spidery feet,

not a big guy who falls

with a resounding thump

and bruises sidewalks and pastures,

sinks in river mud to the waist.

If my feet were spears I would have descended

to a tumultuous underground river that are

everywhere, earth-borne by the black current.

When young I thought I’d die in my thirties

like so many of my favorite poets.

At seventy-five I see this hasn’t happened.

Still, I am faithful to my poems and birds.

Birds are poems I haven’t caught yet.

Jim Harrison

from Dead Man’s Float

Copper Canyon Press, 2015

In cosmological or Darwinian terms, a millennium is but an instant. So let us fast forward not for a few centuries or millennia, but for an astronomical timescale millions of times longer than that. The stellar births and deaths in our galaxy will gradually proceed more slowly, until jolted by the environmental shock of an impact with the Andromeda Galaxy, maybe four billion years hence. The debris of our galaxy, Andromeda and their smaller companions—which now make up what is called the Local Group—will thereafter aggregate into one amorphous swarm of stars. Many billions of years after that, gravitational attraction will be overwhelmed by a mysterious force latent in empty space that pushes galaxies apart from each other. Galaxies accelerate away and disappear over a horizon. All that will be left in view, after 100bn years, will be the dead and dying stars of our Local Group, which could continue for trillions of years. Against the darkening background, sub-atomic particles such as protons may decay, dark matter particles annihilate and black holes evaporate—and then silence.

In cosmological or Darwinian terms, a millennium is but an instant. So let us fast forward not for a few centuries or millennia, but for an astronomical timescale millions of times longer than that. The stellar births and deaths in our galaxy will gradually proceed more slowly, until jolted by the environmental shock of an impact with the Andromeda Galaxy, maybe four billion years hence. The debris of our galaxy, Andromeda and their smaller companions—which now make up what is called the Local Group—will thereafter aggregate into one amorphous swarm of stars. Many billions of years after that, gravitational attraction will be overwhelmed by a mysterious force latent in empty space that pushes galaxies apart from each other. Galaxies accelerate away and disappear over a horizon. All that will be left in view, after 100bn years, will be the dead and dying stars of our Local Group, which could continue for trillions of years. Against the darkening background, sub-atomic particles such as protons may decay, dark matter particles annihilate and black holes evaporate—and then silence. Plastic is everywhere, and suddenly we have decided that is a very bad thing. Until recently, plastic enjoyed a sort of anonymity in ubiquity: we were so thoroughly surrounded that we hardly noticed it. You might be surprised to learn, for instance, that today’s cars and planes are, by volume, about 50% plastic. More clothing is made out of polyester and nylon, both plastics, than cotton or wool. Plastic is also used in minute quantities as an adhesive to seal the vast majority of the 60bn teabags used in Britain each year.

Plastic is everywhere, and suddenly we have decided that is a very bad thing. Until recently, plastic enjoyed a sort of anonymity in ubiquity: we were so thoroughly surrounded that we hardly noticed it. You might be surprised to learn, for instance, that today’s cars and planes are, by volume, about 50% plastic. More clothing is made out of polyester and nylon, both plastics, than cotton or wool. Plastic is also used in minute quantities as an adhesive to seal the vast majority of the 60bn teabags used in Britain each year. One evening this fall at a house in West Hollywood,

One evening this fall at a house in West Hollywood, Derek Mahon’s new volume of poems, Against the Clock, again proves him one of the greatest contemporary masters of poetic form. Preoccupied as he is with his advancing age and the “final deadline” looming in the future, the suppleness and subtleness of his flexible rhythms and rhymes keep the subject from becoming ponderous. Mahon knows all about the dark side of life, but has an extraordinary ability to set his style against it, as it were, so that his formal ingenuity provides a counterweight. It would be false to say that the darkness is vanquished ‑ it is not. A Mahon poem does not engage in illusionary antics or light-headed optimism. It knows the type of world in which it must reside. But its own energy carries it through with panache: “life is short and time, the great reminder, / closes the file of new poems in line / for the printer and binder” ‑ and these lines in parenthesis no less. Rhymes as unusual as “reminder” and “binder” abound in this volume, and display one of Mahon’s greatest talents: his ability to take so-called traditional forms and subject them to change and play. At this point in his career it seems effortless. His play with the units of poetic form is creative to the point of ingenuity ‑ but not quite, since Mahon sets himself against ingenuity for its own sake, or wordplay that is not anchored by deep feeling. And yet “play” is the right word for what this serious poet allows himself to do, and perhaps must do.

Derek Mahon’s new volume of poems, Against the Clock, again proves him one of the greatest contemporary masters of poetic form. Preoccupied as he is with his advancing age and the “final deadline” looming in the future, the suppleness and subtleness of his flexible rhythms and rhymes keep the subject from becoming ponderous. Mahon knows all about the dark side of life, but has an extraordinary ability to set his style against it, as it were, so that his formal ingenuity provides a counterweight. It would be false to say that the darkness is vanquished ‑ it is not. A Mahon poem does not engage in illusionary antics or light-headed optimism. It knows the type of world in which it must reside. But its own energy carries it through with panache: “life is short and time, the great reminder, / closes the file of new poems in line / for the printer and binder” ‑ and these lines in parenthesis no less. Rhymes as unusual as “reminder” and “binder” abound in this volume, and display one of Mahon’s greatest talents: his ability to take so-called traditional forms and subject them to change and play. At this point in his career it seems effortless. His play with the units of poetic form is creative to the point of ingenuity ‑ but not quite, since Mahon sets himself against ingenuity for its own sake, or wordplay that is not anchored by deep feeling. And yet “play” is the right word for what this serious poet allows himself to do, and perhaps must do. “Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin

“Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin  ‘Like

‘Like  At Wayne State University, a commuter campus in Detroit where faculty members and students struggle to turn people out for events, the

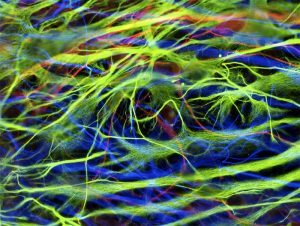

At Wayne State University, a commuter campus in Detroit where faculty members and students struggle to turn people out for events, the  Japanese neurosurgeons have implanted ‘reprogrammed’ stem cells into the brain of a patient with Parkinson’s disease for the first time. The condition is only the second for which a therapy has been trialled using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are developed by reprogramming the cells of body tissues such as skin so that they revert to an embryonic-like state, from which they can morph into other cell types. Scientists at Kyoto University use the technique to transform iPS cells into precursors to the neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. A shortage of neurons producing dopamine in people with Parkinson’s disease can lead to tremors and difficulty walking.

Japanese neurosurgeons have implanted ‘reprogrammed’ stem cells into the brain of a patient with Parkinson’s disease for the first time. The condition is only the second for which a therapy has been trialled using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are developed by reprogramming the cells of body tissues such as skin so that they revert to an embryonic-like state, from which they can morph into other cell types. Scientists at Kyoto University use the technique to transform iPS cells into precursors to the neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. A shortage of neurons producing dopamine in people with Parkinson’s disease can lead to tremors and difficulty walking. Seven years since the heady days of

Seven years since the heady days of  In

In  For millions of soldiers, the

For millions of soldiers, the  Scholars have built a tight historical and corresponding conceptual link between the advent of the rectangular, Renaissance frame and the advent of linear perspective. It’s true that the renovation of Fra Angelico’s San Domenico altarpiece entailed both, but this was usually not the case. In 1480, about a century and a half after it was made, Giotto’s altarpiece for the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce was renovated. Its original frame was removed and discarded, along with God the Father, who had occupied the gable above the heads of the Virgin and Christ. Spandrels decorated with vermilion cherubim were added, along with a new, rectangular frame that slices right through the curves of the cusped arches.

Scholars have built a tight historical and corresponding conceptual link between the advent of the rectangular, Renaissance frame and the advent of linear perspective. It’s true that the renovation of Fra Angelico’s San Domenico altarpiece entailed both, but this was usually not the case. In 1480, about a century and a half after it was made, Giotto’s altarpiece for the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce was renovated. Its original frame was removed and discarded, along with God the Father, who had occupied the gable above the heads of the Virgin and Christ. Spandrels decorated with vermilion cherubim were added, along with a new, rectangular frame that slices right through the curves of the cusped arches. ‘A dragon is no idle fancy,’ wrote Tolkien in 1936, but ‘a potent creation of men’s imagination, richer in significance than his barrow is in gold’. The potency has only increased over the last eighty years. Dragons crowd the pages of modern fantasy; no one needs telling that Daenerys, the Mother of Dragons, holds a crucial place in George R R Martin’s Game of Thrones universe.

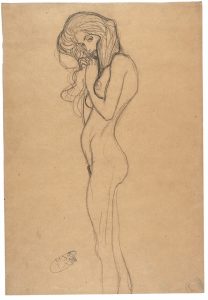

‘A dragon is no idle fancy,’ wrote Tolkien in 1936, but ‘a potent creation of men’s imagination, richer in significance than his barrow is in gold’. The potency has only increased over the last eighty years. Dragons crowd the pages of modern fantasy; no one needs telling that Daenerys, the Mother of Dragons, holds a crucial place in George R R Martin’s Game of Thrones universe. Although it was Klimt’s paintings that first impressed Schiele, especially a solo show in 1908, the two men didn’t meet until the following year when they established a strong rapport and exchanged drawings. The role of drawings occupied a different place in the art of each man. The majority of Klimt’s were composed with paintings in mind but he also made private works, often quickly executed, that deviated from the ideal of heady beauty that permeated his paintings. Sketches of his elderly mother or a nude pregnant woman past the first flush of youth shed stylisation for an unflinching intimacy. Sometimes he didn’t bother with limbs, while figures fill the sheet like columns, cropped at the head and feet. Schiele, though, took it all in.

Although it was Klimt’s paintings that first impressed Schiele, especially a solo show in 1908, the two men didn’t meet until the following year when they established a strong rapport and exchanged drawings. The role of drawings occupied a different place in the art of each man. The majority of Klimt’s were composed with paintings in mind but he also made private works, often quickly executed, that deviated from the ideal of heady beauty that permeated his paintings. Sketches of his elderly mother or a nude pregnant woman past the first flush of youth shed stylisation for an unflinching intimacy. Sometimes he didn’t bother with limbs, while figures fill the sheet like columns, cropped at the head and feet. Schiele, though, took it all in.