by Joseph Carter Milholland

In my last column, I wrote about the interconnectedness of the literary canon. My argument was that canonical books are best read in the context of other canonical books – that we only fully appreciate a great work of literature when we also appreciate the other great works it is inextricably bound to – both the books that influenced it, and the books it influenced.

I will admit that this argument can lead one astray: if applied improperly, we lose sight of individual authors and individual works, and only focus on the narrative of literary history. Worse yet, we will arbitrarily force certain books to conform to our expectations of the canon, instead of reading them on their own terms. I do not think that there is anything in what I proposed that would necessarily lead to this kind of reading, but it is a very easy mistake to make (and one I will confess to having made in the past). To avoid making this mistake, I will now propose a complementary method for reading the canon: to seek out and understand the difference between what I call the “mainstream” and the “marginal.”

I am using the terms mainstream and the marginal to denote two types of literary artistry. Whenever we read a great book, there is a wide spectrum of ways in which we enjoy it: on the right end of this spectrum, we have the kinds of enjoyment that we can find in almost every great book, no matter where or when it was written; in the center is the ways in which the book reflects the finest features of a specific genre or literary tradition; and on the far left is the way in which that particular book gives us its own unique pleasures. The literary artistry that falls in the right hand end of this spectrum I call the mainstream, and the artistry on the left hand side I call the marginal. I realize this definition is abstract and somewhat cumbersome, so throughout this essay I will supply examples that I think better illuminate what I am getting at. My first example: the catharsis we experience at the end of great tragedy is an example of mainstream artistry; the caesura in Anglo-Saxon verse is an example of marginal artistry.

Some more clarifications are in order. Read more »

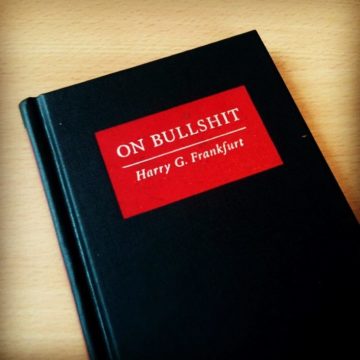

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics.

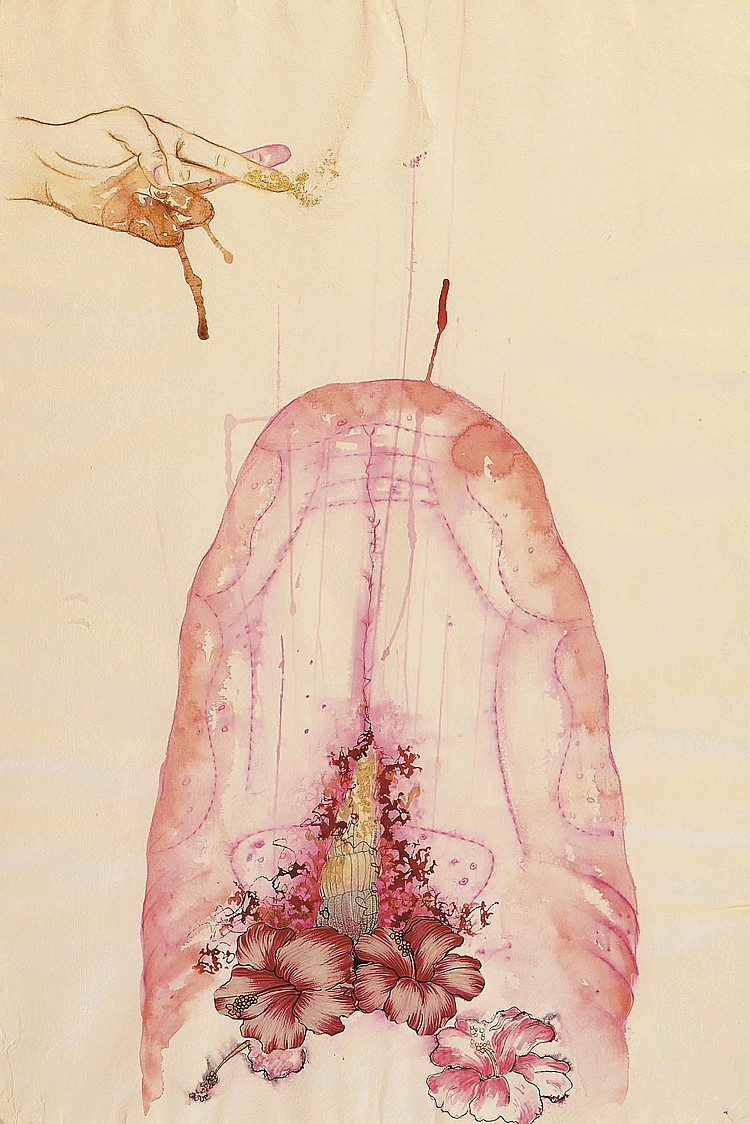

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics. Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work.

Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work. ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say

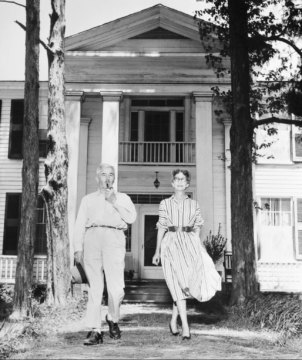

ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say  The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

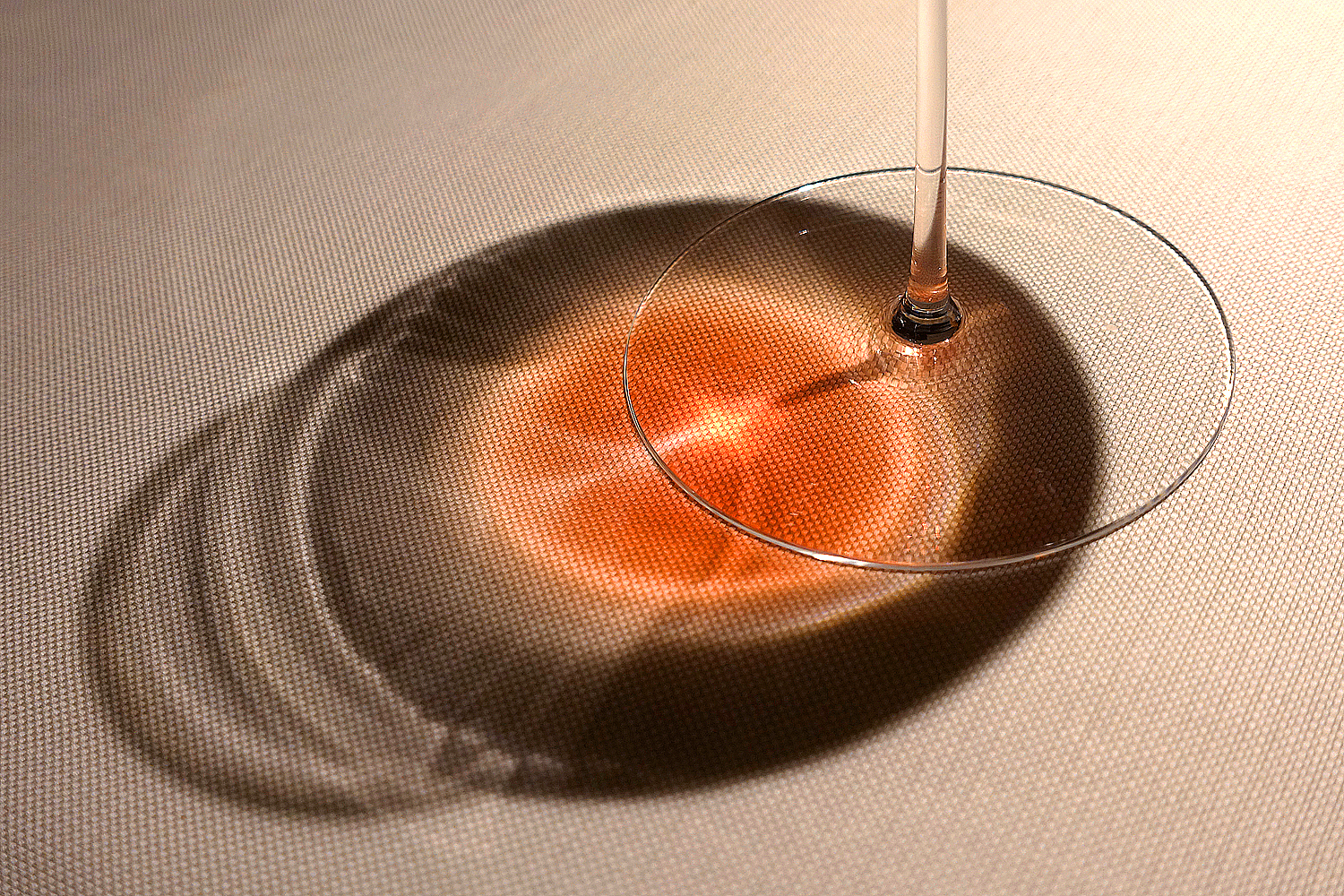

Today marks eight years since I had my last drink. Or maybe yesterday marks that anniversary; I’m not sure. It was that kind of last drink. The kind of last drink that ends with the memory of concrete coming up to meet your head like a pillow, of red and blue lights reflected off the early morning pavement on the bridge near your house, the only sound cricket buzz in the dewy August hours before dawn. The kind of last drink that isn’t necessarily so different from the drink before it, but made only truly exemplary by the fact that there was never a drink after it (at least so far, God willing). My sobriety – as a choice, an identity, a life-raft – is something that those closest to me are aware of, and certainly any reader of my essays will note references to having quit drinking, especially if they’re similarly afflicted and are able to discern the liquor-soaked bread-crumbs that I sprinkle throughout my prose. But I’ve consciously avoided personalizing sobriety too much, out of fear of being a recovery writer, or of having to speak on behalf of a shockingly misunderstood group of people (there is cowardice in that position). Mostly, however, my relative silence is because we tribe of reformed dipsomaniacs are a superstitious lot, and if anything, that’s what keeps me from emphatically declaring my sobriety as such.

Today marks eight years since I had my last drink. Or maybe yesterday marks that anniversary; I’m not sure. It was that kind of last drink. The kind of last drink that ends with the memory of concrete coming up to meet your head like a pillow, of red and blue lights reflected off the early morning pavement on the bridge near your house, the only sound cricket buzz in the dewy August hours before dawn. The kind of last drink that isn’t necessarily so different from the drink before it, but made only truly exemplary by the fact that there was never a drink after it (at least so far, God willing). My sobriety – as a choice, an identity, a life-raft – is something that those closest to me are aware of, and certainly any reader of my essays will note references to having quit drinking, especially if they’re similarly afflicted and are able to discern the liquor-soaked bread-crumbs that I sprinkle throughout my prose. But I’ve consciously avoided personalizing sobriety too much, out of fear of being a recovery writer, or of having to speak on behalf of a shockingly misunderstood group of people (there is cowardice in that position). Mostly, however, my relative silence is because we tribe of reformed dipsomaniacs are a superstitious lot, and if anything, that’s what keeps me from emphatically declaring my sobriety as such.