by Chris Horner

Imagine you are put in regular close contact with someone who regularly makes your life difficult. This could be at work, or a flat share, anything. They leave you to finish the chores they start, invade your space, and generally act in an inconsiderate way. You’d like to put some space between them and you, but you can’t. Perhaps you’ve some choice words for them which you are preparing to share, but holding back your exasperation you try to point out to the person the problems they are causing. When you start to do that, this person responds by disclosing that they have a condition that, according to them, makes them act in this way. For our purposes this could be anything: ADHD, autism, PTSD, neurosis stemming from childhood neglect, bipolar – anything (to be clear: I am not suggesting that any of these are necessarily connected to antisocial behaviour; let’s also assume that they aren’t inventing the diagnosis, and that the condition is real). [1]

How does this change your feelings about the situation, if at all? Perhaps you try to talk through the situation to find a way to work with this person to mitigate the antisocial behaviour. But it continues. You might find a way of leaving the situation, or of getting outside assistance. You might check that there has been a legitimate medical diagnosis, all sorts of things. Suppose the condition has been diagnosed by a qualified person. So they do have this condition. Again: what has changed? Read more »

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

Over the years I’ve been teaching, many people have asked me about the content of an elementary course I teach. I’m interested in the syllabi and exams of courses in other fields, so this I hope may be of interest to others as well. The survey course on which this exam is based is a smorgasbord of probability, voting theory, scaling, and other variable material. Since the class is very large, I often reluctantly make the final exam multiple choice as is the example below. Try it if you like. Two hours is all the time you have. Writing useful prompts for ChatGPT will take too long to be of much help.

Over the years I’ve been teaching, many people have asked me about the content of an elementary course I teach. I’m interested in the syllabi and exams of courses in other fields, so this I hope may be of interest to others as well. The survey course on which this exam is based is a smorgasbord of probability, voting theory, scaling, and other variable material. Since the class is very large, I often reluctantly make the final exam multiple choice as is the example below. Try it if you like. Two hours is all the time you have. Writing useful prompts for ChatGPT will take too long to be of much help.

In

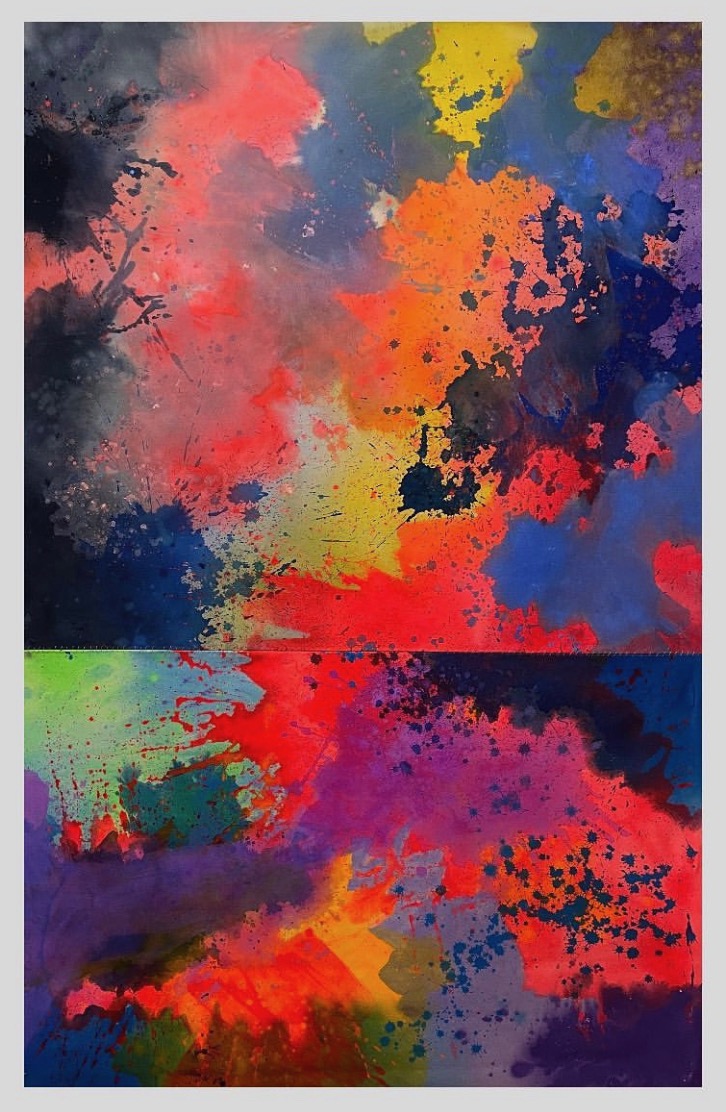

In  Rashida Abuwala. Untitled Diptych, 2023.

Rashida Abuwala. Untitled Diptych, 2023.

The other day, one of my grandsons asked me if I’d like to play Mario Kart with him. It goes against my grain to turn down invitations from my grandsons. However, when we’d played Mario Kart a few weeks earlier, I’d been terrible at it. His younger brother, watching from the sidelines, wanted to know why I played so badly. I said it was because the game was new to me, but in fact I’ve always been slow and clumsy at games that require quick reactions and hand-eye coordination, back to Pac-Man and even earlier. As an undergrad I was good at an arcade version of Trivial Pursuit, but that cuts no ice with anyone these days.

The other day, one of my grandsons asked me if I’d like to play Mario Kart with him. It goes against my grain to turn down invitations from my grandsons. However, when we’d played Mario Kart a few weeks earlier, I’d been terrible at it. His younger brother, watching from the sidelines, wanted to know why I played so badly. I said it was because the game was new to me, but in fact I’ve always been slow and clumsy at games that require quick reactions and hand-eye coordination, back to Pac-Man and even earlier. As an undergrad I was good at an arcade version of Trivial Pursuit, but that cuts no ice with anyone these days.

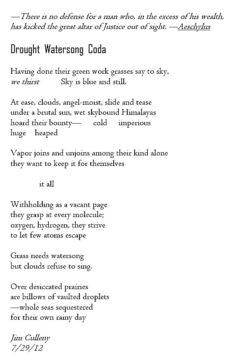

In geometry, a line goes on and on: it goes on and on and never stops. In poetry, a line goes on as long as the poet lets it….though in practice this rarely means more than six or seven words at a stretch.

In geometry, a line goes on and on: it goes on and on and never stops. In poetry, a line goes on as long as the poet lets it….though in practice this rarely means more than six or seven words at a stretch.