by Tom Jacobs

I do not know if it has ever been noted before that one of the main characteristics of life is discreteness. Unless a film of flesh envelops us, we die. Man exists only insofar as he is separated from his surroundings. The cranium is a space-traveler's helmet. Stay inside or you perish. Death is divestment, death is communion. It may be wonderful to mix with the landscape, but to do so is the end of the tender ego. —Vladimir Nabokov, Pnin.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood

And sorry that I could not travel both… —Robert Frost

No, I'm kidding. At least about the second one. One has to choose epigraphs carefully. Even if Bobby Frost was onto something there, it's too hackneyed and clichéd and infinitely deployed at every commencement speech to ever be retrieved from the abyss of misuse. It's not his fault. It's a good poem though, and although he could never have foreseen it, the sentiment strikes waaaay too many of the notes that are appropriable by those who might misuse it, who might tend to want to give advice. Even me. Even if he's spot on. So no Bobby Frost. At least not right away. Maybe later.

Our heads are space-traveler's helmets. How strange it is to think that, although we all lug about with us long and complicated social histories, histories that are totally invisible but very heavy—to think that all of this is contained in a rather thin and delicate envelope that reveal nothing about who we really are.

These are a few things and life lessons that I think I might have learned.

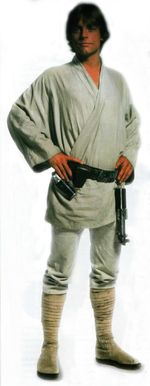

I think of Luke Skywalker. I think of old Luke Skywalker. The fella from Tatooine. The father we never found.

I think of Luke Skywalker. I think of old Luke Skywalker. The fella from Tatooine. The father we never found.

I recall going to see the 20th anniversary re-release of Star Wars and loving it and then walking out of the theater feeling oddly sad. Actually not sad; full on melancholy, rather; the kind of anxiety and profound unhappiness that rattles at your very sense of who you are and might become or could have been. At the time I couldn't quite identify the source of my sadness and melancholy. Eventually I did. Here's what I came to understand and what continues to reverberate:

When I first saw Star Wars, I was five, but I was old enough to recognize a hero when I was one. Luke Skywalker was, what, maybe 21? The age of a hero. Not to old, not too young. He would always be 21, eternally and forever on film. By the time I saw the re-release in 1997, I had aged and had surpassed the heroic age of 21, even if Luke had not. I found myself to be older than Luke, who would remain 21 forever. And however many times I had envisioned it happening in one shape or another—the notion of some mentor tapping me on the shoulder to point out that I was, in fact, and whether I realized it or not, a rather remarkable Jedi-like individual, one who had a role to play in the larger intergalactic battle between good and evil, between right and wrong—it never quite happened, at least not in the shape or form that I had anticipated. No Obi Wan ever tapped me on the shoulder. The hero's journey that I imagined for myself never quite emerged. Which is not to say that it hasn't happened.

I had always imagined the dramatic moment, the decisive cut, the transformative moment when everything changes (the moment when Obi Wan takes me to the cantina and I realize that I'm on the threshold and that if I go out, and if I return, I will not return in the same form or shape… Everything will change).

Life is far too subtle for that sort of thing. Too discrete and full of nuance and ambiguity. I think we all are, potential Jedi Knights, even if we continue to wait for Obi Wan Kenobi to come. Maybe he has already come and tapped and asked, even if we never understood or recognized it at the time. I think he probably has.

In the spirit of someone who is constantly looking for his own Obi Wan Kenobi, here are some thoughts from someone who knows nothing and is adviceless. Or maybe that's not exactly right. I have learned a few things. No doubt these are obvious and well-known to you. No matter. Let me re-iterate and re-galvanize.

Read more »