by Max Sirak

It turns out you learn a lot when you write a book. This may seem counterintuitive. Perhaps you think, “Well, that’s dumb. If you write a book about something you should already be an expert on it.”

It turns out you learn a lot when you write a book. This may seem counterintuitive. Perhaps you think, “Well, that’s dumb. If you write a book about something you should already be an expert on it.”

That’s a fair way to feel and thing to say.

However, my situation is slightly more unique. See, I don’t write books on subjects I’m an expert in. (I’m not even sure if such subjects exist.) My job as a ghostwriter is to help other people write books in their fields of expertise. It goes like this: most people spend their lives practicing and learning all they can in their fields. Then, after years of gaining proficiency, there almost inevitably comes a time for them to share their hard- won wisdom. The best way to do this, they figure, is to write a book.

That’s where I come in. Usually, the process of becoming a badass in a given field doesn’t entail much writing. Sometimes it does, certainly. But most occupations don’t involve a lot of “writing.” Paperwork? Probably. Reports to fill and file? Likely. But there’s where the pen stops.

So, most folks have spent all their time working toward being the best whatever-it-is-they-are, not writing. I, on the other hand, write every day. Which means, when it comes time for others to share what they’ve learned with the masses, I can help.

And that, friends, is why you are now being treated to a single, kidless guy’s thoughts on parenting. Read more »

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

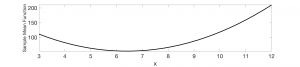

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

“It’s a long, long way from the Trump administration to an actual fascist dictatorship,” I said, “but it’s a straight line.”

“It’s a long, long way from the Trump administration to an actual fascist dictatorship,” I said, “but it’s a straight line.” It was all another day of Trump TV. Another day when all eyes were on Trump. Another day when headlines ran with his name splashed across the front page all over the world. Another day when memes were shared on Facebook and twitter. And another day people expressed feeling incredibly offended over and over again.

It was all another day of Trump TV. Another day when all eyes were on Trump. Another day when headlines ran with his name splashed across the front page all over the world. Another day when memes were shared on Facebook and twitter. And another day people expressed feeling incredibly offended over and over again.

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.

Political debates in Europe these days seem to have only one subject. At one point or another they all turn to the issue of migration, Islam, and a danger to “the West”, which are presented as essentially synonymous. Germany’s political future seems currently to

Political debates in Europe these days seem to have only one subject. At one point or another they all turn to the issue of migration, Islam, and a danger to “the West”, which are presented as essentially synonymous. Germany’s political future seems currently to