Hanaa Malallah. Something I Have Learnt. 2013.

Ink, digital print, mixed media, on artist’s paper.

“…shimmering through the leaves and out beyond the black lines

of her neighbors’ chimney pots were the stars, beacons whose light

left them long before there were eyes on this planet to receive it…”

…………………………………………….. — archeologist Jacquetta Hawkes

Tripping on Curbs

we who live in deep space and trip

on curbs looking up at stars bound in a mesh

of interstices of lightyears through which

seas of breath and blood pass,

in which muscles are bound by mystic ligaments

to armatures of bone . . .

we’re always mystified by what seems a

phenomenal disconnect,

mindsparks shine here and there,

filaments of personal matter,

electric turns of tissue and dreams,

tiny conscious blips to which

oldest light comes, goes, scatters

and everything is it.

so it may not matter

if shimmering it

will or will not

shatter

.

Jim Culleny

11/04/16

by Brooks Riley

by Amanda Beth Peery

by Gabrielle C. Durham

“In receiving this award, I thank my parents, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Mr. T.”

“In receiving this award, I thank my parents, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Mr. T.”

This is my twist on the importance of the serial or Oxford comma, the comma that should follow “Gabor” and precede “and.” I was indoctrinated at a young age, which as we know is the best time for a spongy brain to take in nebulous rules that will dictate the rest of one’s life. The catechist was grammar and its incumbent style guide. Style guides rule the world. They frame the content you read, no matter if you notice it. You probably only become aware of it if the framing is inadequate or a convention is broken.

In a just and decent world, everyone would use the Chicago Manual of Style. That august association does not give me any money, but I would give (and have given) them some for the joy and clarity that publication and its website have bestowed upon me. If you’re looking for some syntactic comedy, check out their reader comments. It’s not a Chris Rock special on premium cable, but you might have a titter.

Chicago has everything. If you cannot find an answer in Chicago, either you did not phrase it correctly or it is not worth asking. Even a worthless question, the magnanimous souls at CMS will find a way to answer and give solace to the asker’s weary mind. Read more »

Siamak Filizadeh. Anis al-Dawla, 2014.

Photograph.

Current show at LACMA In The Field of Empty Days.

” … In the Fields of Empty Days explores the continuous and inescapable presence of the past in Iranian society. This notion is revealed in art and literature in which ancient kings and heroes are used in later contexts as paradigms of virtue or as objects of derision, while long-gone Shi‘ite saints are evoked as champions of the poor and the oppressed. Beginning in the 14th century, illustrated versions of the Shahnama or Book of Kings, the national epic, recast Iran’s pre-Islamic kings and heroes as contemporary Islamic rulers and were used to justify and legitimize the ruling elite. Iran’s adoption of Shi‘ite Islam in the early 16th century also helped to fix the past irrevocably in the present through the cycle of remembrance of the martyrdom of Shi‘ite Imams. Both of these strands—olden kings and heroes, and martyred Imams—carry forward, even sometimes overlap, in contemporary Iranian art, rendered anachronistically as a form of often barely disguised social commentary.”

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

The hour was late, but it was still hot. Frijoles Canyon loomed to my right, showcasing its surfeit of stratigraphic tuff and igneous ash layerings and ponderosa pines. I was about a hundred and fifty feet up on the mountain face in a reconstructed cave with a ceremonial kiva or well. The cave was accessible by climbing a series of narrow steps and four ladders inclined against the steep rocks: not recommended for those with a fear of heights. On this particular day I was alone there; it was a hot weekend, and not too many hikers and tourists had scattered themselves around Bandelier National Park where the cave’s located.

It’s tough not to fall in love with the American Southwest. There is no other part of the United States which combines so uniquely and generously Native American, Spanish and Anglo-American culture with spectacular desert and mountain expanses as far out as the eye can see. Our trip had started with the Grand Canyon, whose first display of infinite recesses and a blaze of colors is sufficient to stop almost any conversation for a few seconds. It had then continued through Indian reservations spread across three states – albeit still crammed into nooks and crannies relative to their original seemingly limitless expanse – which took us through the incredible towering structures of Monument Valley to New Mexico. Read more »

Blowing Her Lungs Out into a Clay Oven

Mother leans

against the island

in the nanosecond kitchen

at Farouk’s home

in New Rochelle,

marveling

at a Miracle Icemaker

as half-moons

tumble

into a glass bowl.

She spins

a Lazy Susan

with glee,

clicks the fire

fountains on & off.

“Atomic food

makes stomachs ache,”

she warns,

alarming

the microwave.

“I remember,”

she says,

“squatting

in front

of a clay oven

blowing

my lungs

into a slim steel pipe

to light a fire,

my smoke-singed eyes,

your father’s anger—

She pulls out

an empty tray

from the oven,

whispers,

“For 50 years

I created

a home

only to see

your father’s

new wife

inherit

it.”

by Rafiq Kathwari / @brownpundit

by Carol Westbrook

I live in a flyover state, Indiana, USA. You know, one of those states that you fly over but you don’t stop in, as you travel East Coast to West Coast or the post-industrial Midwest. You know, the vast prairies where no one important lives, mostly rural and small town. Where the people are mostly white, socially conservative highly religious and staunchly Republicans. Where there are too few people to influence national politics. You know, the ones who put Donald Trump in office.

This May, I was the Election Inspector for the primaries in our precinct, Pine 2, of Porter County, Indiana. Porter County is not exactly flyover country–we’re more of a hybrid flyover/northern city. We are tucked into the northwest corner of Indiana, a region filled with heavy industry and a few large cities on the shores of Lake Michigan. Our population, 166,000, is only 3% that of Chicago, and is 93% white.

County, Indiana. Porter County is not exactly flyover country–we’re more of a hybrid flyover/northern city. We are tucked into the northwest corner of Indiana, a region filled with heavy industry and a few large cities on the shores of Lake Michigan. Our population, 166,000, is only 3% that of Chicago, and is 93% white.

Pine 2 is only 60 miles from Chicago and is filling with Chicago expatriates seeking lower property and sales tax, cheaper houses, or wooded country retreats an easy hour commute to Chicago. Pine 2 itself has no industry, but it includes my little town of Beverly Shores, which houses a high proportion of artists, intellectuals, Chicago commuters and retired University of Chicago professors. Democrats outnumber Republicans three to one. The other 132 precincts of Porter County, though, are truly flyover country. Forty percent is farmland; it is is dotted with small towns and small industry. It is socially and politically conservative, strongly religious, and staunchly Republican. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Max Sirak

Long before it ever even occurred to me to be a writer, I accidentally adopted the quirks and habits of one…

If one sits in my dining room, they can see it. There is literal writing on my wall. What once stood empty, with its deep red paint, is now plastered with Post-Its. My dining room features a Word-of-the-day wall. It took over five years to complete and started as many things do, by chance, during a drunken game of Scrabble.

Word-of-the-day-wall aside, there’s another writerly habit this column pertains to.

I can’t honestly tell you when I started my notes. Soon after college is all I’ve really got. Many moons ago I began highlighting passages in everything I read and typing them up. It’s a labor of love born in hopes of retention.

I learned at university that if I wanted to commit something to memory I needed to do more than simply read it. Remembering, for me, requires an action element. So, in the name of not forgetting everything I was learning from books, I started my notes.

Weighing in at damn near three-quarters of a million words, over 1,500 pages, and spanning 200 different entries, my notes are the closest thing to a life’s work I’ve got. Read more »

Subway Haiku

Five times doors open

And five times they quickly shut

The Speaker crackles

Crossroads of the world

Four languages on my bench

Train to JFK

Many tired folks,

Long hours and they can’t rest yet,

“start spreadin’ the news”

Every type of eyes:

Closed, squinting, staring, empty,

Downcast, roving, hard

Dude: Yankees’ cap,

Whitest sneakers known to man,

Brand names head to toe

“No way” says a kid,

Mom grabs his DS away,

He stares silently.

Man wears a kuf,

On his neck: Star of David,

Eating some pork rinds

Man in uniform,

Knows how important he is,

And now you do, too

Women gently sleep,

The train lurches to a stop,

They ain’t sleeping now. Read more »

by Carl Pierer

Yazd, one of the big three Tourist destinations in central Iran, has a rather challenging climate. With summer temperatures often exceeding 40C and hardly any precipitation at all (49 mm per year), water is a major concern. The city is rightfully famous for its wind towers (بادگیر) and qanats (قنات). While the former were and sometimes still are used for cooling houses, water reservoirs or storage rooms, the latter used to provide the city with water. Walking through the city, located in this rather inhospitable environment, one is constantly reminded that question of water dominates many aspects of life: from the garden and parks to agriculture and industry, from housing location to food storage and cooling. For many of these, the ingenious use of qanats provided an answer.

Writing in 1968, Paul English [2] states that in Iran alone 15 million acres (roughly 6 million hectares, or 60.000 km2) of cultivated land are watered by 37.500 qanats. This, at the time, corresponded to between one-third and a half of the total cultivated land. Historically, they provided up to ¾ of the water used in Iran. [1] Being such an important feature of Iranian cities, it is worth looking at some of their technical details. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Dave Maier

So Sam Harris, Jordan Peterson, and a number of other brash rebels daring to challenge the stifling intellectual status quo, in which one is not allowed to criticize anyone from other cultures, because multiculturalism or Marxism or something, are part of, I am not making this up, the Intellectual Dark Web. Fine, whatever. It’s not that there’s no such thing as lefty orthodoxy, obviously, especially on campus, but these best-selling authors look pretty petty presenting themselves as somehow being silenced.

Anyway, that’s not what I want to talk about. In the New York Times piece telling us about all this, I ran across the following exchange:

After [Harris’s] talk, in which he disparaged the Taliban, a biologist who would go on to serve on President Barack Obama’s Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues approached him. “I remember she said: ‘That’s just your opinion. How can you say that forcing women to wear burqas is wrong?’ But to me it’s just obvious that forcing women to live their lives inside bags is wrong. I gave her another example: What if we found a culture that was ritually blinding every third child? And she actually said, ‘It would depend on why they were doing it.’” His jaw, he said, “actually fell open.”

It’s not unprecedented, or even unusual, that Harris should commit a philosophy fail. But in detaching ourselves from error, we have to be careful about where we end up. It’s not even clear, for example, that his point in the context is threatened by his futile sally. So I’ll be defending him as much as diagnosing his (all too common) error. Maybe I should be on the IDW too. Help, I’m being silenced!

Okay, enough japery for now. What did Harris do wrong here, and why may his main point survive the stumble? Read more »

by Michael Liss

Celebrate with me.

May is graduation month, and my children are among the graduates. My son marched two weeks ago for his Masters, and, if you are reading this on Memorial Day, it might be at the very same time I watch my daughter receive her Bachelor of Music. Go get ‘em, kids.

Perhaps your joy need not be vicarious—you have your own family skittering across the podium. One of the special pleasures of this time of year is that so many of your friends and relations are also submerged in a sea of caps and gowns, blurry pictures, hugs, and the dreaded Elgar Pomp and Circumstance Earworm. They announce themselves with each vibration from your iPhone, a kaleidoscope of happy, and occasionally goofy, images. Can we all stipulate that the whole outfit looks a bit silly?

Graduation also reminds you that time passes (way too fast). Your kids’ time, and your time. You’ve changed, just as has the five-year old who came bouncing out of her room, a huge grin on her face, ready for the first day of Kindergarten. You are a little older (just a little) and a little more “robust,” and your times in the Road Runners races are “moving” in the wrong direction.

It doesn’t matter. There are your children, not looking little at all, promising you a peculiar type of immortality. They are going to go do things, great things, going to change the world. They are the discoverers, the communicators, the creators. They will wash away any imperfections you’ve left and build things bigger and better. They really are the future.

You’ve celebrated with me. Now, indulge me. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

It’s an exhaustive list. Far longer and deeper than you might suspect. The Tribune tracks U.S. school shootings of the past 50 years. A well documented list by Wikipedia goes back to 1840, when a student named Joseph Semmes shot University of Virginia law professor John Anthony Gardner Davis.

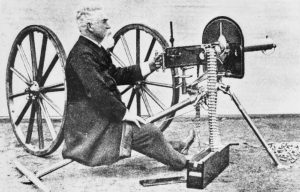

Three more school shootings occurred in the 1850s, when guns were substantially different weapons than they are now. The revolver had been invented in the 1830s, and rifles were beginning to replace muskets, but Hiram Maxim’s machine gun was still decades away. And even when they did arrive, automatic weapons were initially quite expensive and difficult to obtain. In response to the gangland violence of the Prohibition Era (1920-33), the federal government effectively regluated automatic weapons with the 1934 National Firearms Act.

Consequently, even as public school education expanded greatly in the United States after the Civil War (1861-65), documented school shootings were sparse and resulted in relatively few deaths for the remainder of the century.

Decade — (No. of School Shootings) — Deaths/injuries

1860s ——————–(6) ———————————8/1

1870s ——————–(7) ———————————4/4

1880s ——————–(11)———————————2/6

1890s ——————–(8)———————————13/19+

Many school shootings from the 1860s-1950s did not unfold they way we now picture them, with a single gunman mowing down masses of people. Indeed, guns were not even always the preferred weapon. More often, American school violence involved knives and fists. As for school shootings, many resulted from spontaneous fights.

In 1893, a fight erupted at a high school dance in Plain Dealing, Louisiana. Two students died on the scene, two more were fatally wounded, and a teacher was also injured.

That same year, six people were killed and at least one injured at a high school in Charleston, West Virginia when one group of students interrupted another’s performance. A teacher intervened, the antagonizing group turned on him, and then other people joined the fray, resulting in a violent melee. The teacher and five others were shot and killed, and one student died from having his skull crushed. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

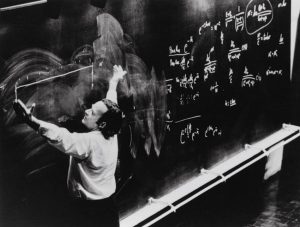

On May 11th, to mark the 100th anniversary of Richard Feynman’s birth, Caltech put on a truly dazzling evening of public talks. I heard that tickets sold-out online in four minutes; and this event was so popular that attendees started queueing up to enter the auditorium an hour before the program began. Held in Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium (the white, perfectly round hall designed by legendary architect Edward Durrell Stone that students sometimes call “the wedding cake”), the line buzzed with excited conversation as people could be heard telling various anecdotes about Feynman. There are so many of Feynman stories! Just as we were about to be let in, I overheard one that always makes me smile; so perfectly does the story capture what Feynman is to Caltech. A gentleman behind me was talking to a friend about his days as an undergraduate at the Institute. He said that he would never forget the time when an upper class-man had explained to him the workings of Caltech’s highly streamlined bureaucracy:

On May 11th, to mark the 100th anniversary of Richard Feynman’s birth, Caltech put on a truly dazzling evening of public talks. I heard that tickets sold-out online in four minutes; and this event was so popular that attendees started queueing up to enter the auditorium an hour before the program began. Held in Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium (the white, perfectly round hall designed by legendary architect Edward Durrell Stone that students sometimes call “the wedding cake”), the line buzzed with excited conversation as people could be heard telling various anecdotes about Feynman. There are so many of Feynman stories! Just as we were about to be let in, I overheard one that always makes me smile; so perfectly does the story capture what Feynman is to Caltech. A gentleman behind me was talking to a friend about his days as an undergraduate at the Institute. He said that he would never forget the time when an upper class-man had explained to him the workings of Caltech’s highly streamlined bureaucracy:

“Basically at Caltech,” the upper class-man had informed him, “There are six division heads who report directly to the provost; who himself only has to answer to the President.”

Amazed at how minimal departmental management was at the institute, he had asked, “Is that it?”

To which his interlocutor had immediately replied: “Well, of course, the president does have to answer to God; who then must answer to Richard Feynman.”

It’s true that Feynman is absolutely venerated at Caltech. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1965, a group of Feynman devotees (aka students) used a ladder to climb up and reach a bas relief sculpture that adorned a high exterior wall in the patio at Dabney House. The sculpture was loosely modeled on Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper and depicted a group of nine scientists (including Newton, Copernicus, Pasteur, Franklin, Archimedes, Euclid, Darwin and Da Vinci) who were gathered around a table with the great Galileo in the center. The students in their excitement over Feynman’s win, proceeded to remove Galileo’s name, replacing it with that of Feynman’s. And no one has dared put Galileo back since! Read more »