by Joshua Wilbur

I first encountered a Big Dumb Object (“BDO”) in an underfunded school library in rural East Texas. Sitting cross-legged on the carpeted floor, I held a battered paperback just a few inches from my face, periodically turning it over to inspect the image on the book’s cover.

Rama.

I was twelve years old—“the real golden age of science-fiction”—and Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama captivated my imagination. The novel’s premise is simple: an alien starship, a massive cylinder of unknown origin and construction, has entered the solar system, and a crew of scientists must investigate. Thin on plot (and even thinner on characterization), Rama lingers in my memory not for what’s hidden within the vessel but for what’s kindled from without, from the mere suggestion of a colossus come from the stars. It stirred in me what sci-fi critics have called the “sense of wonder,” a feeling of awe that courses through the heart of the genre.

Nothing better epitomizes this sense of wonder than “Big Dumb Objects,” a term coined by Roz Kaveney and lovingly adopted by fans of the science fiction genre. BDOs, as you’ll have guessed, are really big, dumb in the old sense of “mute, silent, refraining from speaking,” and usually serve as a focal point for narrative action. Mysterious thing is discovered; mysterious thing is explored. In a Weird Things column for The Guardian, Damien Walter defines the BDO:

“ … the Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a unique selling point of the sci-fi genre. It can be a broad term – usually, they’re alien architectures, ranging from the man-sized to the planetary. BDOs either look extreme or unusual, and can often do extreme or unusual things: everything from lurking on a horizon to creating worlds. Usually, BDOs are plonked into plots to awe us with their majesty and mystery – really, they’re science fiction’s equivalent of a MacGuffin.” Read more »

“Beware of literature!” This warning occurs in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea as an entry in the diary of the narrator, Antoine Roquentin. In context, it concerns the way that literary narratives falsify our experience of events by investing them with an organization and structure that our experiences in themselves, as we live them, do not have. When Bilbo Baggins finds the ring in The Hobbit, Tolkein tells us that although Bilbo didn’t realize it at the time, this would turn out to be a turning point in his life. When married couples recall their first meeting, their account inevitably packages the event as a “beginning,” even though they may have had no inkling of this at the time.

“Beware of literature!” This warning occurs in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea as an entry in the diary of the narrator, Antoine Roquentin. In context, it concerns the way that literary narratives falsify our experience of events by investing them with an organization and structure that our experiences in themselves, as we live them, do not have. When Bilbo Baggins finds the ring in The Hobbit, Tolkein tells us that although Bilbo didn’t realize it at the time, this would turn out to be a turning point in his life. When married couples recall their first meeting, their account inevitably packages the event as a “beginning,” even though they may have had no inkling of this at the time. Do you find this prospect upsetting? Perhaps you think it is unfair for someone to get a job without a good reason for why they deserve it rather than anyone else. Perhaps you think such a system would decrease your chances of getting the job you want. If so then you may be under the influence of the cult of excellence.

Do you find this prospect upsetting? Perhaps you think it is unfair for someone to get a job without a good reason for why they deserve it rather than anyone else. Perhaps you think such a system would decrease your chances of getting the job you want. If so then you may be under the influence of the cult of excellence.

In the 70s our church caught bus fever as an effort to bring in the sheaves with greater volume (we pass the salvation savings on to you!). We began deploying a fleet of ancient school buses, painted Baptist blue, out into the neighborhoods of town to bring anyone that so wished to church. Heathen parents gleefully signed up their kids so they could read the paper and drink coffee in peace. Today such an effort would be like inviting people to sue you and then providing a free ride to the courthouse. Come for the mass transit; stay for the litigation.

In the 70s our church caught bus fever as an effort to bring in the sheaves with greater volume (we pass the salvation savings on to you!). We began deploying a fleet of ancient school buses, painted Baptist blue, out into the neighborhoods of town to bring anyone that so wished to church. Heathen parents gleefully signed up their kids so they could read the paper and drink coffee in peace. Today such an effort would be like inviting people to sue you and then providing a free ride to the courthouse. Come for the mass transit; stay for the litigation.

When the father of your child is in jail, pray even if you don’t believe in God. Pray even though in your head of heads you know it won’t do shit. Stop staring at the walls, at the clock, at the phone. At your baby, now eight, sleeping next to you, his sneakers, caked with mud, still tied to his feet. Pray because it will distract you from what’s coming, from a conversation millions of mothers have already had with their sons. You are not different, not an exception to some rule. Start praying instead of feeling sorry for yourself. Buck the fuck up because he will need you.

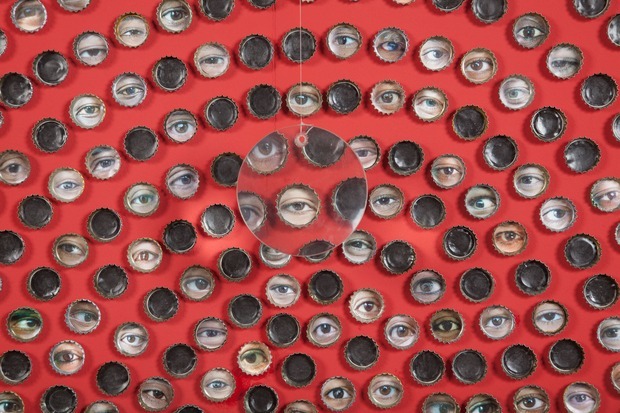

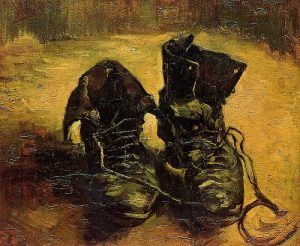

When the father of your child is in jail, pray even if you don’t believe in God. Pray even though in your head of heads you know it won’t do shit. Stop staring at the walls, at the clock, at the phone. At your baby, now eight, sleeping next to you, his sneakers, caked with mud, still tied to his feet. Pray because it will distract you from what’s coming, from a conversation millions of mothers have already had with their sons. You are not different, not an exception to some rule. Start praying instead of feeling sorry for yourself. Buck the fuck up because he will need you. Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.

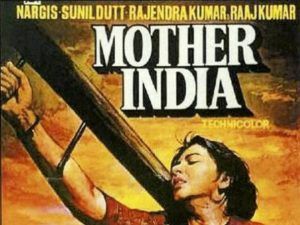

Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.  Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens.

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens.