by Emily Ogden

When Donald Trump was elected, I was pregnant with twins. My sons were born after the 2017 inauguration, under what I cannot help but feel is an ill star—though in themselves they are privileged and want for nothing. Nothing, that is, except a planet whose future is secure and a nation that does not “reign without a rival” for “revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy”—words of Frederick Douglass’s whose restless sound wave has kept propagating itself. My sons were learning to crawl when white supremacists marched in downtown Charlottesville, a mile from our house. They started walking at about the time that NPR played recordings of children wailing in detention centers. No crisis that has come, has passed. Another election is approaching; talk of impeachment grows serious. And my sons, oblivious to all of this, are asking for stories.

“Story bout that,” they say, when some event, or more commonly some non-event, captures their attention. In the dark, Beckettian world of their fictions, little happens except for a persistent breaching of bodily integrity. Here are some of the stories; judge for yourself (L. and N. are my sons, and Zeke is one of our dogs):

When L. got stung by a bee

When N. got stung by an ant

When N. got a splinter in his foot

When a wheel fell off the neighbor’s pickup truck

When Zeke broke [killed] the snake

When Zeke broke the lizard

When the weather broke

When a bowl broke

When L. had broken skin

When the red balloon went up to the ceiling and we couldn’t reach

When Zeke got out the front door

When N. was coughing so hard he gagged

When the red baby cried

Things break and people break and we, the tellers of stories, survive. That is the common burden of these monotonous, unstructured downers, each of which I have been ordered to tell at least fifty times. My sons listen, calm as sucklings. Why such an appetite for damage? It reflects their reality, I suppose. Toddlers fall and they destroy things. I understand the appeal of Humpty Dumpty without the need to search for royalist intimations. An egg, who is at once a fragile person and a fragile object, shatters beyond repair. Welcome to my household. My sons have had several great falls each, and they have broken literally dozens of literal eggs. Read more »

I remember the first time I thought I might be able to get on board with Stoicism. I read a

I remember the first time I thought I might be able to get on board with Stoicism. I read a

Do you remember when the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw suggested significant changes to English spelling so that it would make more sense? Probably not, because it was more than 70 years ago. According to him

Do you remember when the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw suggested significant changes to English spelling so that it would make more sense? Probably not, because it was more than 70 years ago. According to him

Things are changing. Always, everywhere, immensely and minutely, the history of mankind unfolds as we rotate around a grand burning star (also, everything everywhere else changes; the history of mankind may be of the least consequence on a cosmic scale, but I digress). I digress too early; I include parentheticals too soon; I stall with flowery descriptions of the sun. Because – ugh – I’m going to talk about “how divided we are as a nation.” It’s such a tired phrase; I don’t want to write about it. It’s stale because it’s static, and anyway, the declaration is often accompanied by divisive rhetoric. Wherever one may fall on the political spectrum (and here I’m being gracious; how often do we now identify with a “side”), they likely have established opinions of those who lie elsewhere. It does seem increasingly difficult to imagine a sweeping reconciliation when we continue to pour our definitions in concrete and defend our positions by reason of consistency. Inflexibility begets inability to listen, and thus to understand, which is why we find our differences so baffling and allow our prejudices to influence our opinions. So, finally, here it is: my own personal take on how we can get people to stop saying how divided we are. Bear with me, because I’m going to try and sell contradictions as potential energy for unity.

Things are changing. Always, everywhere, immensely and minutely, the history of mankind unfolds as we rotate around a grand burning star (also, everything everywhere else changes; the history of mankind may be of the least consequence on a cosmic scale, but I digress). I digress too early; I include parentheticals too soon; I stall with flowery descriptions of the sun. Because – ugh – I’m going to talk about “how divided we are as a nation.” It’s such a tired phrase; I don’t want to write about it. It’s stale because it’s static, and anyway, the declaration is often accompanied by divisive rhetoric. Wherever one may fall on the political spectrum (and here I’m being gracious; how often do we now identify with a “side”), they likely have established opinions of those who lie elsewhere. It does seem increasingly difficult to imagine a sweeping reconciliation when we continue to pour our definitions in concrete and defend our positions by reason of consistency. Inflexibility begets inability to listen, and thus to understand, which is why we find our differences so baffling and allow our prejudices to influence our opinions. So, finally, here it is: my own personal take on how we can get people to stop saying how divided we are. Bear with me, because I’m going to try and sell contradictions as potential energy for unity.

Firstly, of course we should rescue the art first. Secondly, of course we should not.

Firstly, of course we should rescue the art first. Secondly, of course we should not.

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles.

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles. A degree in engineering from India, grad school at an American university, and a job at an American corporation: call it the Indian-engineer version of the American dream. Like hundreds of thousands of Indian immigrants, Ved, the 36-year old protagonist of

A degree in engineering from India, grad school at an American university, and a job at an American corporation: call it the Indian-engineer version of the American dream. Like hundreds of thousands of Indian immigrants, Ved, the 36-year old protagonist of

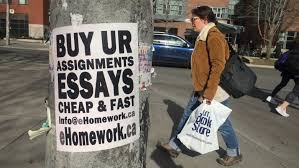

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them;

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them; A while ago findingtimetowrite wrote a

A while ago findingtimetowrite wrote a

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.