by Chris Horner

In my years in education I have regularly come across what I call the lightbulb fallacy: the view that people have degrees of brightness and that it is the job of education to measure the wattage of learners in order to find the best social sockets to plug them into. It is a noxious idea. The notion that intelligence is a measurable ‘something’ that is possessed by people in varying degrees is one of the ways in which we end up with an education system that fails the majority of those it is supposed to be helping. It damages not just those in schools and colleges but people in general, and it is based on a fallacy about what it is to learn and understand.

One can see a number of reasons why adopting a notion like this would seem useful for an education system like ours: if people have amounts of intelligence that can be identified and measured, then people can be classified and fitted into the place in education, and later in the economy, that will suit their degree of ‘brightness’. But the problem is that people aren’t like lightbulbs with differing degrees of wattage, and this essentialising approach, that imputes a fundamental, intrinsic trait to an individual, leaves most people experiencing education as a demotivating process in which they learn to experience themselves as failures. Examinations put the seal on this by placing students in an ascending hierarchy of brightness. The effect of this on many, if not most, learners is unhelpful, to put it mildly. As an educator I have had to deal with numerous situations in which students have in effect used this as an alibi for giving up, since if those other students are brighter than oneself, why bother? Of course, not every learner reacts to lower marks in that way – but most get the message, in the end, that they cannot get far up the ladder of educational achievement, and that success is the preserve of a small number of the very bright. Read more »

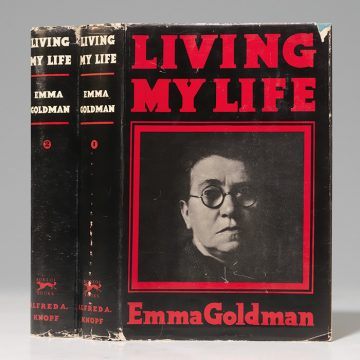

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

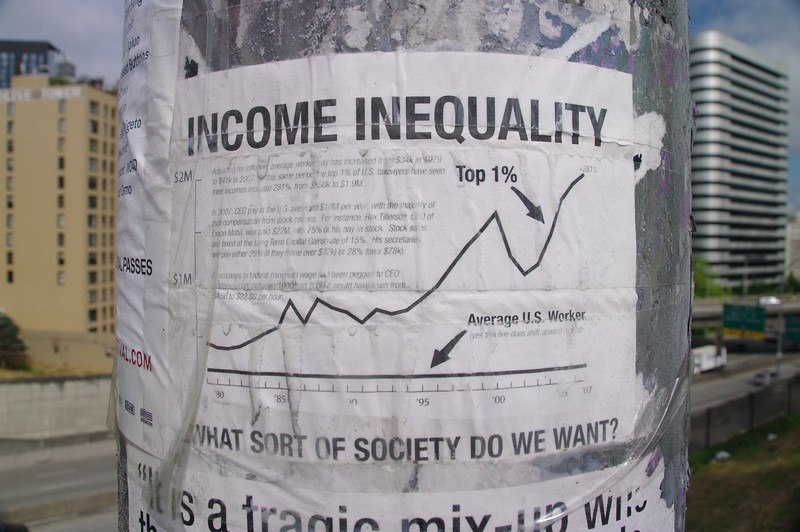

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life. There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “ Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside.

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside. Trapped

Trapped