Andi. Untitled. Jokgakarta, Indonesia.

Batik art on fabric.

Digital photograph by Sughra Raza.

Andi. Untitled. Jokgakarta, Indonesia.

Batik art on fabric.

Digital photograph by Sughra Raza.

by Liam Heneghan

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Being of a scientific inclination, the royal couple assigned twenty children to each of five experimental groups. They prevented these children from mingling—for keeping the groups apart was deemed good experimental practice—and assessed if reading matters asking following questions. Should one read aloud to children, or narrate stories of a parent’s own devising, or read and discuss plot points at length as one proceeds through storytime, or should one perhaps, as early as possible, cultivate the youth to read on their own and abandon them to their own devices? One group of children—“our little controls” as the happy couple called them—were raised without the benefit of any stories at all.

The results of this longitudinal study were alas inconclusive. The prince haughtily accused his wife of surreptitiously reading to the control group; the princess icily retorted that her husband’s monotonic voice had lulled everyone asleep thus undermining the study. “I’d sooner stab myself in the ears than listen to another word from you.” Their scientific paper was rejected for publication; the couple lost their funding. And they all lived happily ever after. Read more »

Dr. Gary Schwartz is a recognized leader in the field of translational research and has been able to connect the basic and clinical science elements of drug development. His research focuses on the identification of new targeted agents for cancer therapy, especially in the treatment of sarcoma and melanoma. He earned NCI K24 and K12 Clinical Oncology Research Career Development Awards aimed at the mentoring of medical trainees in translational research. Moreover, he has authored about 200 papers and 17 book chapters in the field of basic and clinical cancer research. He currently serves as the Chief of the Division of Hematology and Oncology and Deputy Director of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University School of Medicine.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Samia Altaf

Baiji, my grandmother, was the custodian of standards of behavior of young women in the family. How to comport oneself — sit, stand, speak, eat—were strictly prescribed according to her rules of what was “proper” practice for girls. These rules did not apply to young men and boys.

Although I found most of Baiji’s rules onerous, it was especially difficult to adhere to one related to what the girls should eat and how much. First on Baiji’s list was meat –of all kinds. Mutton, beef and fish were strictly forbidden. Organ meat could not be mentioned in the same sentence that had the word girls in it. Neither were eggs, or butter or cream or rich edible oils. Nuts—walnuts, cashews and specially almonds—were also prohibited.

Once in a while, on special occasions such as Eid or at family weddings, girls could eat meat–in moderation. In winter they could have almonds —but no more than five a day. Peanuts were allowed but just a fistful, no more, at a time. Basic dry cereals, bread without butter, vegetables and fruits—these too in moderation—were best for girls. These foods kept them calm and of a clear mind, she said. Meat and such were “hot” and prone to causing agitation in women. Pregnant women and lactating mothers had special privileges. Even then, though calorie rich foods such as butter were fine, as were eggs — meat was still considered too extravagant for them. Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

There’s a well-established notion in film theory referred to as the “male gaze”. Here’s its description according to the theorist Laura Mulvey, who first introduced the concept in her 1975 essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. Mulvey suggests that, in Hollywood films, “the determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female form which is styled accordingly” (my emphasis).

According to Mulvey, the (heterosexual) male gaze reduces female figures in films to mere objects, devoid of agency and incapable of advancing the cinematic narrative. As she analyzes it, mainstream cinema makes the viewer complicit in this gaze. It places the viewer in the position of identifying with the male actors, who advance the plot, and to treat the female characters in films as scenery. Women in films, on Mulvey’s analysis, can serves as objects and frames for the action, but men are the sole actors.

I was reminded of the notion of the “male gaze” when reading an essay by L.D. Burnett on the occasion of Harold Bloom’s death, in a piece at the Society for US Intellectual History blog. Burnett’s essay reminded me that, without detracting from the incisiveness of Mulvey’s analysis, it is important to recognize there are other roles to which men can seek to consign women.

There’s a particular one of these roles that I have in mind, one that I haven’t seen discussed before in quite the way that Burnett’s discussion sparked for me. I’ll call it the “imagined female gaze”. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Katie Poore

A few weeks ago, I journeyed up to Chamonix-Mont-Blanc during a work vacation. I went with a few friends of mine, embarking from our homes in Chambéry, France, taking a train to Annecy, and a bus to our final destination. I was outrageously tired, having stayed up until some ungodly hour of the morning playing, of all things, Just Dance.

After shuffling around Annecy for a few hours, laden down with luggage and waiting for the arrival of our bus, we were on our way into the so-called heart of the French Alps. As badly as I wanted to sleep, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the changing landscape, framed through immense bus windows. I pressed my forehead against the glass and turned on some music, hoping to block out any sounds of more mundane humanity for just a moment. Views like this always felt too sacred for human chatter, for the faint rumble of an engine. I couldn’t do much about the vibrating of the bus, or the fact that I was on a bus at all, but this I needed: a world composed of only those things which have taken great thought and time.

For me, this was those mountains and Gregory Alan Isakov, a singer-songwriter and farmer based near Boulder, Colorado, who writes his songs in a barn-studio plastered with giant pieces of paper scrawled with potential song lyrics. He calls songwriting “laborious” in an interview with Atwood Magazine, but this labor gives way to music that is something else entirely: quietly transcendent, aching, longing, at once fragile and formidable. It feels clear that these songs are constructed slowly, scrupulously, mined from the depths of feeling. Anyone familiar with that so-often agonizing creative process might feel the erasures and changes, the takes and retakes, the immense and fatiguing degree of ceaseless thought and emotion that slowly amalgamates to form each of his compositions.

It felt like the only proper music to which I might listen: carefully composed and somehow soaring, a perfect sonic accompaniment to the mountains whose formations might well be described the same way. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Vitality, in a related sense, is also an organoleptic property of a wine—it can be tasted. When we taste them, quality wines exhibit constant variation, dynamic development, and a felt potency, a sensation of expansion, contraction, and velocity that contribute to a wine’s distinctive personality. These features are much prized among contemporary wine lovers who seek freshness and tension in their wines. Thus, wine expresses vitality both as an ontological condition and as a collection of aesthetic properties.

However, this expression of vitality in both senses is fading in aged wines. In aged wines, freshness and dynamism can be tasted but only as vestigial as the fruit dries out and recedes behind leather, nut and earthy aromas. Appreciation of aged wines (at least those wines worthy of being aged) requires that we see delicacy, shyness, restraint, composure, equanimity, imperfection, and the ephemeral as normative. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

Welcome to the future, which is now the past. As James Gleick argued (in his thoughtful and entertaining book, Time Travel: A History) the concept of the future is now fodder for historical understanding. As Gleick notes in his book, popular culture provides a key insight into how ideas about the future shaped the past, present, and the actual future.1

Pop culture during the twentieth century has long imagined the near and far future. Such imaginings became a running gag for talk show host Conan O’Brien. Back in the late 1990s, he started a new segment on his show, called “In the Year 2000.” It started first with him and his co-host Andy Richter (and later guests he was interviewing) donning collars and lighting up their faces with flashlights, while the band played futuristic sounding music in the background. Then, a round of predictions based on current events, ridiculous and silly predictions, all set to happen in the far off future of the year 2000. This bit continued well into the new millennium. Only during O’Brien’s all too-short stint hosting the famed Tonight Show did the format change to predict events in the year 3000 (with Captain Kirk himself, William Shatner providing a regular voice over—although once it was Lt. Sulu instead, George Takei).

The joke revolved around the idea that the future was already here, but the year “2000” still sounds pretty futuristic. Plus, it plays on how we viewed the future across the breadth of the twentieth century, as culminating in a utopia of technological progress, inevitably leading to social progress. Think Disney’s Epcot Center or Gene Roddenberry’s hopeful, post-scarcity, racially unified vision of the future in Star Trek. But O’Brien also pointed to a new phenomenon, when dates from popular culture in what was once the future recede into the past. I argue in this essay that the future we imagined in the past both shaped the present and contradicts it. This becomes clearest when we examine how some science fiction films or TV shows imagined a future date in our recent past. I’ll take three examples, the first being the classic anime, Neon Genesis Evangelion (set in 2015). The second is Ridley Scott’s classic adaptation of Phillip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Blade Runner (set in 2019). Last will be two events in the Star Trek universe: one set in our recent past (the Eugenics Wars) and one in the near future (the Bell riots). Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a new weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. A Prologue can be found here. A table of contents with links to previous chapters can be found here.

I went away to college. The so-called Freshman Fifteen, which many new students pack on when given access to unlimited cafeteria food, was only a fiver on me. And it melted away during my sophomore year. All through my 20s, the tape continued to read 5’9½” and 120 lbs.

To this day, I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone naturally skinnier than I was back then. The only few I ever did meet were all very determined and unhealthy. But me? Just my natural and inexorable state of being. I didn’t overeat, but I certainly didn’t eat healthy. Pizza and fast food made up a shocking share of my diet. Cooking at home was rare and it rarely got beyond ramen or mac n cheese. I could be very active, or I could lay on the couch for months. Didn’t matter. Five-nine and a half, a buck-twenty. Read more »

by Michael Liss

Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

As you might imagine, with that as background, I approached Willful: How We Choose What We Do with a bit of primal trepidation, something deep inside my limbic system. To add to my anxiety, I had just seen a review of the latest Piketty missive under the ominous headline “Thomas Piketty’s new War and Peace-sized book…” and wondered what kind of dense read I was getting myself into.

I was wrong. Once Mr. Robb’s book was in my hands, I realized that I was looking at an entirely different animal, one that didn’t scream at or lecture you, but, in calm, measured tones laid out a fairly remarkable thesis—that existing, accepted theories of why we do things (such as the redoubtable “Rational Choice”) don’t tell the whole story. We aren’t all calculating machines all the time, either consciously or subconsciously doing the math to maximize the return from each transaction. Rather, as humans, we can be motivated by individual, personal factors that have meaning and value to us beyond just what a rational choice analysis might direct. These factors go into the process of what Mr. Robb calls “For-Itself Choice.” Read more »

If you talk about it, it’s not Tao

If you name it, it’s something else

What can’t be named is eternal

Naming splits the eternal to smithereens

…………………………… —Lao Tzu, 6th Century BC

at first I think, I’ve got it!

then I think, Ah no, that’s not it

I think, it’s more like a flaming arrow

shot into the marrow

of the bony part of everything

………. but some summer nights

………. it’s hanging overhead so bright

then right there I lose it

I let geometry and time confuse it

then it’s silent and won’t sing a thing

………. but some summer nights

………. it’s croaking from a pond so right

then again I lose it

let theology and time confuse it

then it’s silent and won’t sing a thing

……………….. I’m thinking I’ve been here before

……………….. feet two inches off the floor

……………….. I’m thinking, is this something true?

sometimes I think, I’ve lost it!

though I never could exhaust it

because it’s lower than low is

and wider than wide is

deeper than deep is

higher than high is

………. but some fresh spring days

………. it’s cuttin’ through the fog and the haze

……………….. I’m thinking I’ve been here before

……………….. feet two inches off the floor

……………….. I’m thinking, is this something true?

by Jim Culleny, 6/15/15

Copyright: Jim Culleny, 6/23/15

by Eric J. Weiner

The word “schlep” comes from the Yiddish “schlepn,” which means to drag or haul. You don’t have to be Jewish to be a schlepper, although it couldn’t hurt. Amidst the deepening economic and political inequities informing everyday life, schlepping is one of the great social equalizers. To see a person in the subway or on the street, schlepless as it were, can be a bit disorienting. Who is this person who can travel so unencumbered? He (and it’s almost always a “he”) must be wealthy and powerful beyond imagination: A king or prince? A tech-guru? A hip-hop mogul? A cannabis hedge fund manager? Maybe he’s a mysterious, self-identified “founder” flush with new money and the freedom from schlepping it buys. Maybe he has “people” to schlep for him. They must be “professional” schleppers undoubtedly paid below a living-wage to schlep things they could never afford to schlep themselves.

Yet at the same time, I look upon this extravagantly empty-handed man-king with a degree of benevolent pity. Nothing to schlep must make traveling through the world an empty, meaningless experience. Absent the things he doesn’t carry how would he know not only where he is but who he is? It is true that we may be more than the sum total of what we schlep, but take away the stuff we schlep and it becomes difficult to know where the measure of who and where we are even begins.

Providing the theoretical and methodological foundation for such an analysis of the things we schlep, Stuart Hall’s (1997) seminal analysis of the Sony Walkman articulates the things people schlep to a general theory of culture itself. For Hall, the things we schlep represent a kind of language and as a consequence the study of cultural artifacts hold enormous promise in helping us understand complex systems of representation, meaning and power. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Hydroglyphs with black fish, Ubud, Bali, 2019.

Digital photograph.

by John Schwenkler

This is the second in a series of posts discussing different ways of pursuing philosophical understanding.

My first post in this series explained how philosophy can aim to help us become articulate about things we already understand at a practical or intuitive level, much as drawing a map makes explicit the knowledge we have in being able to find our way around a certain place.

At the end of the post I considered several objections to this project, including that it is too conservative and uncritical to count as a philosophical endeavor. According to this objection, the project I envisioned is inadequate because of the way takes our ordinary ways of thinking for granted and isn’t concerned to replace our philosophical beliefs with better ones. At the end of this post I will explain again why I think this objection misfires, but first I want to discuss a different approach to philosophy that has an opposite orientation in these respects, and consequently takes a quite different stance on the value of “common sense.”

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the Meditations on First Philosophy, capture beautifully the attractiveness of this alternative philosophical project. Descartes titled his first meditation, “Of the things which may be brought within the sphere of the doubtful,” and it begins as follows:

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the Meditations on First Philosophy, capture beautifully the attractiveness of this alternative philosophical project. Descartes titled his first meditation, “Of the things which may be brought within the sphere of the doubtful,” and it begins as follows:

It is now some years since I detected how many were the false beliefs that I had from my earliest youth admitted as true, and how doubtful was everything I had since constructed on this basis; and from that time I was convinced that I must once for all seriously undertake to rid myself of all the opinions which I had formerly accepted, and commence to build anew from the foundation, if I wanted to establish any firm and permanent structure in the sciences.

Many people know of the famous thought experiment that Descartes develops in the subsequent pages, in which he imagines that all his thoughts and perceptions are the product of “an evil genius … [who] has employed his whole energies in deceiving me.” For Descartes, the purpose of this thought experiment was to rein in the habits of credulity that had led him in his youth to admit false things as true ones. He was instead to adopt a skeptical attitude, believing only those things whose truth he could see for himself in a “clear and distinct” way. Read more »

by Dave Maier

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

It then proceeds to attribute this ghastly sentiment to the Seattle Public School district, on the basis of a preliminary document for a proposed curriculum in “Math Ethnic Studies.” Other critics of this pseudo-educational abomination are cited; math, they agree, is an area “which all people should be able to view as objectively settled.” To doubt this is to fall prey to the worst postmodern relativism and skepticism. And so on, in familiar fashion.

I’m not here to defend the Seattle Public School district specifically, nor multiculturalism in general, nor postmodern relativism and skepticism, for that matter. But to respond to the first two with the same tired 90s-era pomo-bashing (“Apparently math is now subjective,” mocks one critic) is to combine sloppy interpretive procedure with half-baked folk philosophy. Let’s put the latter aside for now and start with the former. Read more »

Dr Robert Gallo, a biomedical researcher, is renowned for his role in the discovery of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the infectious agent responsible for AIDS and in the development of HIV blood tests. He co-founded Profectus BioSciences, Inc., a biotechnology company. Profectus develops and commercializes technologies to reduce the morbidity and mortality caused by human viral diseases. He is also a co-founder and scientific director of Global Virus Network. He is the director and co-founder of the Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. In November 2011, Dr Gallo was named the first Homer & Martha Gudelsky Distinguished Professor in Medicine.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Rafaël Newman

In the spring of 1991 I crossed the German-Polish border at Görlitz and travelled through Zgorzelec, the city’s one-time other half across the river Neisse, into Poland.

The Gulf War had just ended, and the streets of Berlin, where I was spending the year at the Freie Universität, were still littered with cardboard coffins, relics of protest against the US-led intervention in Iraq. A recent visit to the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, to see the Berliner Ensemble perform Brecht’s Die Maßnahme, had been disrupted by activists clambering on stage with a banner that read, “THIS IS WAR: NO MORE EVERYDAY LIFE”, a neatly ironic iteration of the playwright’s own tactic of estrangement as a defense against complacency and the hypocritical respite provided by bourgeois entertainment. Moreover, whispered confabs at the Staatsbibliothek with fellow students at my American grad school also currently abroad were being met with glares of more than usually acid disapproval from locals. So it seemed like a good time to get out of town for a while.

A recently acquired Berlin friend had planned a car trip to Poland to visit family – or rather, the Polish friends who had assisted his German relatives when they were made to leave their “ancestral” home on the Baltic following the Second World War, when that part of Germany was “restored” to Poland, for a new residence on the Rhine – and I invited myself along for part of the ride: from Berlin, by way of Görlitz/Zgorzelec, to Breslau, now Wrocław, where I would part company with my friend before he headed north to Gdynia, his family’s former home. Read more »

by R. Passov

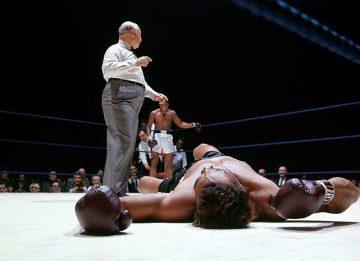

The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC) provides a short history of boxing. It’s an ancient sport. The Romans fought each other wearing cestus, sometimes to the death. Before them so the Greeks. In the fourth century AD, tired of the violence, the Romans outlaw the sport.

According to the BBBofC, fourteen hundred years pass before boxing re-appears in London as an organized sport for bettors. In 1719, a James Figg is recognized as the First Heavyweight Champion. His protégé, John Broughton introduces rules. A century later, John Graham fighting for the 8th Marquis of Queensberry, codifies the rules as the Queensberry Rules, which still govern the sport:

A boxer shall wear gloves. Wrestling is not allowed. The match is no longer a fight to the finish. Rounds shall last for three minutes. A boxer must rise before a 10 second count and the match shall be fought in a standardized ring – more or less.

Queensberry Rules also include – No shoes or boots with springs and a man hanging off the ropes with his toes off the ground shall be considered down. Read more »