by Michael Liss

The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for, not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given control of the property interests of the country, and upon the successful Management of which so much depends. —George Baer, President of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, during the Coal Strike of 1902.

Whenever I read yet another article about intramural warfare in the Democratic Party over which candidate will be progressive enough for the Progressive wing, I think about that quote.

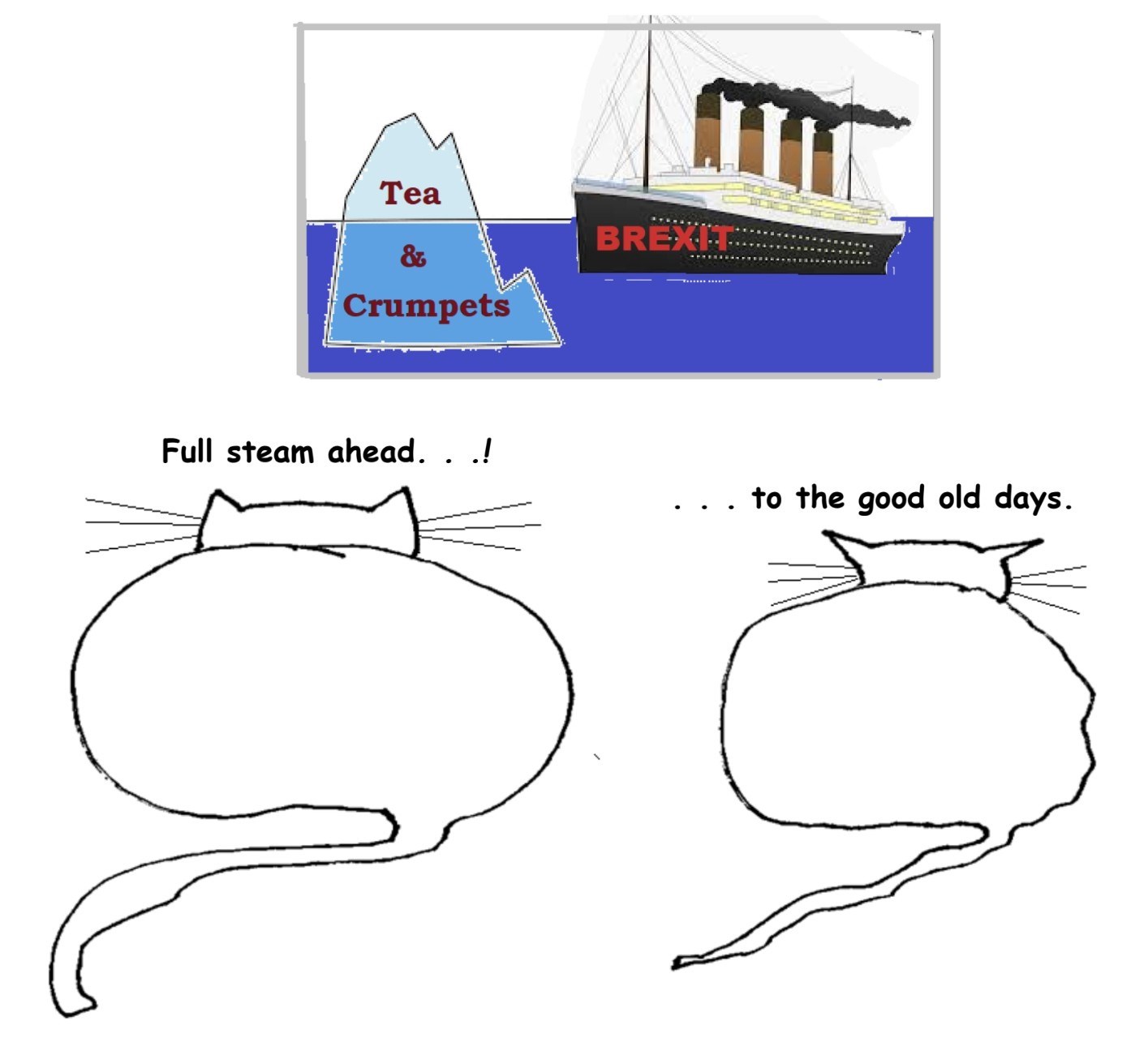

Know your enemy, know yourself. Do contemporary Progressive politicians really know either? The “old” Progressivism, which reached its zenith in the period between 1896 to 1916, was primarily a social and political reform movement. Faced with the excesses of the unbridled capitalism of the Gilded Age that had preceded it, it did not look first toward redistribution. Rather, it took aim at the pervasive rot that was created as immense wealth was being made in businesses like mining, railroads, shipping, steel, meatpacking, and finance, often at the expense of the working man, the farmer, and the small businessman. From this, it drew its moral force.

We should acknowledge that those fortunes were the product of the efforts of real visionaries, larger-than-life figures like Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, James J. Hill, the Armour and Swift families, J.P. Morgan, Rockefeller, and Carnegie. Talent aside, though, their successes were enhanced by the sharpest, most predatory tactics, of the type described in Ida Tarbell’s The History of The Standard Oil Company, a 19 part series in McClure’s Magazine, which chronicled the rise of Standard Oil. Business was not for the faint of heart, and the most successful businessmen were monopolists who went from strength to strength, squeezing every competitor, and every last dollar, out of every transaction.

No matter how entrepreneurial the businessman, no matter how rich the oilfield, no matter how coldly efficient the operator, it couldn’t have been done without grease. Corruption was literally everywhere. Read more »

Banners waved, the converted preached and hawkers peddled hats, buttons, “Impeach This” sweatshirts and dodgy conspiracy theories. T

Banners waved, the converted preached and hawkers peddled hats, buttons, “Impeach This” sweatshirts and dodgy conspiracy theories. T Welcome to Des Moines, where unmarked satellite trucks troll snowy streets, coffee houses and hotel lobbies are broadcast-ready, and legions of reporters and crew and a few political tourists have swept up and besieged an entire town.

Welcome to Des Moines, where unmarked satellite trucks troll snowy streets, coffee houses and hotel lobbies are broadcast-ready, and legions of reporters and crew and a few political tourists have swept up and besieged an entire town.

First off, let me just get this out of the way: we share too much data about ourselves knowingly with companies and they collect, use and share even more than most of us are aware of (read through those lengthy privacy notices recently?). And unless you live in Europe with its pretty extensive GDPR rules, or

First off, let me just get this out of the way: we share too much data about ourselves knowingly with companies and they collect, use and share even more than most of us are aware of (read through those lengthy privacy notices recently?). And unless you live in Europe with its pretty extensive GDPR rules, or  Another not-necessarily-the-best-of-the-year mix, but there do seem to be a number of 2019 releases. Warning: this one’s pretty drony, so don’t be driving or anything. Sequencers next time, I promise! (A few anyway.)

Another not-necessarily-the-best-of-the-year mix, but there do seem to be a number of 2019 releases. Warning: this one’s pretty drony, so don’t be driving or anything. Sequencers next time, I promise! (A few anyway.)

You’ve been an on-again, off-again working band for a decade. During that period there have been numerous breakups and seemingly endless lineup changes. Then, after years of grinding and uncertainty, you finally hit it big in 1975. You earned it.

You’ve been an on-again, off-again working band for a decade. During that period there have been numerous breakups and seemingly endless lineup changes. Then, after years of grinding and uncertainty, you finally hit it big in 1975. You earned it. At least since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 the issue of Conscientious Objection (henceforth CO) has been an important one in the context of Catholic hospitals and women patients. Such hospitals object to the provision of abortions, contraceptives, sterilization, fertility care, and “gender-affirming care” such as hormone treatments and surgeries.

At least since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 the issue of Conscientious Objection (henceforth CO) has been an important one in the context of Catholic hospitals and women patients. Such hospitals object to the provision of abortions, contraceptives, sterilization, fertility care, and “gender-affirming care” such as hormone treatments and surgeries.

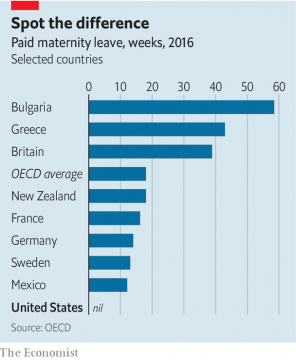

The United States continues to be virtually the

The United States continues to be virtually the  Sughra Raza. Rorschach on the River Li. Yangshuo, China, January, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Rorschach on the River Li. Yangshuo, China, January, 2020. While you might not break into a neighbor’s house to log onto your Facebook account if your internet were down, a case can be made that many of us are victims of at least a moderate behavioral addiction when it comes to our smartphones. At the playground with our kids, we’re on our phones. At dinner with friends, we’re on our phones. In the middle of the night. At the movies. At a concert. At a funeral. (I was recently at a memorial service for my friend’s mother, and someone’s cell phone rang during my friend’s reminiscence.)

While you might not break into a neighbor’s house to log onto your Facebook account if your internet were down, a case can be made that many of us are victims of at least a moderate behavioral addiction when it comes to our smartphones. At the playground with our kids, we’re on our phones. At dinner with friends, we’re on our phones. In the middle of the night. At the movies. At a concert. At a funeral. (I was recently at a memorial service for my friend’s mother, and someone’s cell phone rang during my friend’s reminiscence.)

When Vienna‘s Albertina Museum exhibition of works by Albrecht Dürer ended in January 2020, it seemed quite possible that several of the masterpieces on display might never again be seen by the public, among them The Great Piece of Turf. This may sound like a dire prediction for a fragile work that is routinely exhibited every decade or so, but as the UN announced recently, we may already have passed the tipping point in the race to save our world and ourselves. A decade from now we may be too engaged in the struggle to survive to focus our attention on a small, exquisite watercolor created 500 years ago.

When Vienna‘s Albertina Museum exhibition of works by Albrecht Dürer ended in January 2020, it seemed quite possible that several of the masterpieces on display might never again be seen by the public, among them The Great Piece of Turf. This may sound like a dire prediction for a fragile work that is routinely exhibited every decade or so, but as the UN announced recently, we may already have passed the tipping point in the race to save our world and ourselves. A decade from now we may be too engaged in the struggle to survive to focus our attention on a small, exquisite watercolor created 500 years ago.