by Dave Maier

Last month in this space I posted the notes to my latest ambient mix, and you may have noticed at that time that in those notes I slagged my own composition “Nothing really” – even in its title! – as being nothing much, and promised to explain later. Here I fulfill that promise.

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

Well, I’ll tell you. Here’s how I made it: first, I fired up one of my many synthesizers (here a software synth called Aparillo, purchased in a discounted bundle with a bunch of other entirely out of control plug-ins from the same developer on this last Black Friday). Then I selected a particular preset supplied by the developer. Then – after adjusting the routing a bit, so that I would record sound rather than MIDI – I clicked Record on my DAW and pressed a single key on my MIDI controller (G4, maybe), and held that key down for about four minutes. There, finished! I didn’t do any further processing (synths tend to have built-in effects now, so that lush reverb is already there in the preset) or mastering or anything. Nor did I tweak the preset’s parameters in any way. It took about five minutes in total, most of which, again, was spent holding the key down and listening.

My questions here seem at first to be of two distinct kinds: conceptual/ontological and evaluative. What is “Nothing really”? Is it a musical composition, or perhaps a composition of another kind? Who composed it? and what determines the answers to these questions? And are they really distinct from evaluative questions, the main such question obviously being: how good (or bad) is it? Here too, what determines that? Read more »

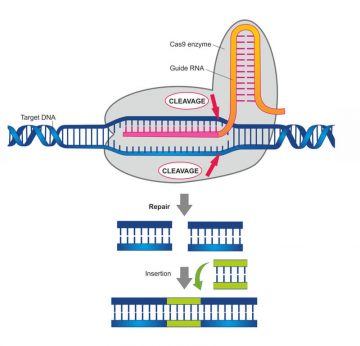

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …”

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …” He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

There should be more.

There should be more. So, here’s a game. Try to imagine: “What unbelievable moral achievements might humanity witness a century from now?” Now, discuss.

So, here’s a game. Try to imagine: “What unbelievable moral achievements might humanity witness a century from now?” Now, discuss. The translated versions from Tamil into English of Perumal Murugan’s two books, One Part Woman and the The Story of A Goat, weave stories of the complex life of the rural people of South India in an engaging and highly readable form.

The translated versions from Tamil into English of Perumal Murugan’s two books, One Part Woman and the The Story of A Goat, weave stories of the complex life of the rural people of South India in an engaging and highly readable form. Jack Youngerman. Long March II, 1965.

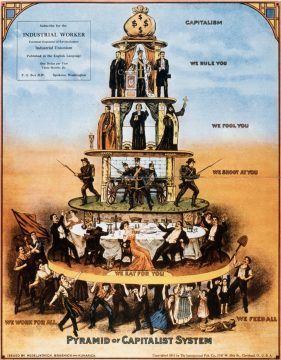

Jack Youngerman. Long March II, 1965. The political philosophy, and more importantly, political practice that took root in the wake of the ‘Age of Revolutions’ (say 1775-1848) was liberalism of various kinds: a commitment to certain principles and practices that eventually came to seem, like any successful ideology, a kind of common sense. With this, however, came a growing sense of dissatisfaction with what it seemed to represent: ‘bourgeois society’. Here is a paradox: at the very point at which the Enlightenment promise of the free society seemed to be coming true, discontent with that promise, or with the way it was being fulfilled, took hold. This was a sense that the modern citizen and subject was somehow still unfree. If this seems at least an aspect of how things stand with us in 2020 it might be worth looking back, for doubts about the liberal project have accompanied it since its inception.

The political philosophy, and more importantly, political practice that took root in the wake of the ‘Age of Revolutions’ (say 1775-1848) was liberalism of various kinds: a commitment to certain principles and practices that eventually came to seem, like any successful ideology, a kind of common sense. With this, however, came a growing sense of dissatisfaction with what it seemed to represent: ‘bourgeois society’. Here is a paradox: at the very point at which the Enlightenment promise of the free society seemed to be coming true, discontent with that promise, or with the way it was being fulfilled, took hold. This was a sense that the modern citizen and subject was somehow still unfree. If this seems at least an aspect of how things stand with us in 2020 it might be worth looking back, for doubts about the liberal project have accompanied it since its inception.

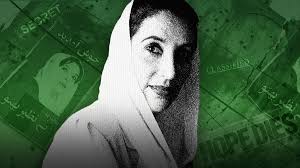

As she returned to her country after eight years of self-imposed exile in Dubai, Benazir reflected in her posthumously-published memoir

As she returned to her country after eight years of self-imposed exile in Dubai, Benazir reflected in her posthumously-published memoir  Gibraltar in the background, I pose sideways, wearing a Spanish Chrysanthemum claw in my hair, gitana style, taking a dare from my husband. The photo is from an August afternoon, captured in the sun’s manic glare. My shadow in profile, with the oversized flower behind my ear, mirrors the shape of Gibraltar, Jabl ut Tariq or “Tariq’s rock.” An actual visit to Gibraltar is more than a decade ahead in the future. I would spend years researching the civilization of al Andalus (Muslim Spain, 711-1492) and publish a book about the convivencia of the Abrahamic people before finally setting foot on Gibraltar. “In Cordoba,” I write, “I’m inside the tremor of exile— the primeval, paramount home of poetry” and that “I am drawn to the world of al Andalus because it is a gift of exiles, a celebration of the cusp and of plural identities, the meeting point of three continents and three faiths, where the drama of boundaries and their blurring took place.” At the heart of this pursuit is my own story, one that is illuminated only recently when I see in Gibraltar more facets of my own exile and encounter with borders.

Gibraltar in the background, I pose sideways, wearing a Spanish Chrysanthemum claw in my hair, gitana style, taking a dare from my husband. The photo is from an August afternoon, captured in the sun’s manic glare. My shadow in profile, with the oversized flower behind my ear, mirrors the shape of Gibraltar, Jabl ut Tariq or “Tariq’s rock.” An actual visit to Gibraltar is more than a decade ahead in the future. I would spend years researching the civilization of al Andalus (Muslim Spain, 711-1492) and publish a book about the convivencia of the Abrahamic people before finally setting foot on Gibraltar. “In Cordoba,” I write, “I’m inside the tremor of exile— the primeval, paramount home of poetry” and that “I am drawn to the world of al Andalus because it is a gift of exiles, a celebration of the cusp and of plural identities, the meeting point of three continents and three faiths, where the drama of boundaries and their blurring took place.” At the heart of this pursuit is my own story, one that is illuminated only recently when I see in Gibraltar more facets of my own exile and encounter with borders.