by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Democracy is a precious social good. Not only is it necessary for legitimate government, in its absence other crucial social goods – liberty, autonomy, individuality, community, and the like – tend to spoil. It is often inferred from this that a perfectly realized democracy would be utopia, a fully just society of self-governing equals working together for their common good. The flip side of this idea is familiar: the political flaws of a society are ultimately due to its falling short of democracy. The thought runs that as democracy is necessary for securing the other most important social goods, any shortfall in the latter must be due to a deviation from the former. This is what led two of the most influential theorists of democracy of the past century, Jane Addams and John Dewey, to hold that the cure for democracy’s ill is always more and better democracy.

The Addams/Dewey view is committed to the further claim that democracy is an ideal that can be approximated, but never achieved. This addition reminds us that the utopia of a fully realized democracy is forever beyond our reach, an ongoing project of striving to more perfectly democratize our individual and collective lives.

This view is certainly attractive. Trouble lies, however, in making the democratic ideal concrete enough to serve as a guide to real-world politics without thereby deflating it of its ennobling character. Typically, as the ideal is made more explicit, one finds that it presumes capacities that go far beyond the capabilities of ordinary citizens. It turns out that democracy isn’t only out of our reach, it’s also not for us. Read more »

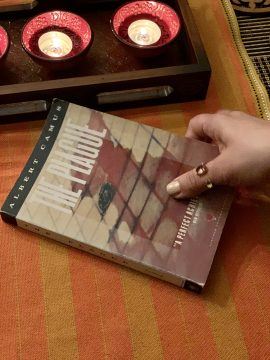

As we continue to distance ourselves from others in the midst of the new coronavirus pandemic, we hear about other people’s new rituals and routines as we formulate our own. As each day to be spent at home stretches (looms) ahead of us when we awake in the morning, rituals give the day shape, symmetry, a framework. What significance do these new rituals have for us individually and as a society? What did the old rituals mean? What if we were to take an anthropological approach to our own predicament?

As we continue to distance ourselves from others in the midst of the new coronavirus pandemic, we hear about other people’s new rituals and routines as we formulate our own. As each day to be spent at home stretches (looms) ahead of us when we awake in the morning, rituals give the day shape, symmetry, a framework. What significance do these new rituals have for us individually and as a society? What did the old rituals mean? What if we were to take an anthropological approach to our own predicament?

Our society needs virologists. Heeding their advice is valuable and consequential. In the Coronavirus pandemic, German politicians listened to the virologists, and Germany is doing relatively well. Other political leaders have (too long) ignored the virologists, and their citizenry is paying a high price.

Our society needs virologists. Heeding their advice is valuable and consequential. In the Coronavirus pandemic, German politicians listened to the virologists, and Germany is doing relatively well. Other political leaders have (too long) ignored the virologists, and their citizenry is paying a high price.

In contrast with other genres in literature, in crime fiction, which mainly started in the mid-19th century, women writers (and even women sleuths) became active around the same time as male writers and sleuths in their stories. By some accounts around the middle of 1860’s, both the first modern detective novels (by female as well as male writers in US, UK and France) and the first professional female detectives in them (one Mrs. G— in one case, Mrs. Paschal in another, both working for the British police) appeared. Most of us, of course, are more familiar with characters in the Golden Age of crime fiction of the 1920’s and the 1930’s, particularly, Agatha Christie’s Miss Jane Marple and Dorothy Sayers’ Harriet Vane. The number of female writers and sleuths has proliferated in recent decades. It goes without saying that not all of the female crime novelists come out as feminists, and that some male writers can do feminist crime novels quite well.

In contrast with other genres in literature, in crime fiction, which mainly started in the mid-19th century, women writers (and even women sleuths) became active around the same time as male writers and sleuths in their stories. By some accounts around the middle of 1860’s, both the first modern detective novels (by female as well as male writers in US, UK and France) and the first professional female detectives in them (one Mrs. G— in one case, Mrs. Paschal in another, both working for the British police) appeared. Most of us, of course, are more familiar with characters in the Golden Age of crime fiction of the 1920’s and the 1930’s, particularly, Agatha Christie’s Miss Jane Marple and Dorothy Sayers’ Harriet Vane. The number of female writers and sleuths has proliferated in recent decades. It goes without saying that not all of the female crime novelists come out as feminists, and that some male writers can do feminist crime novels quite well.

Sughra Raza. Untitled; Arnold Arboretum, Boston, March, 2020.

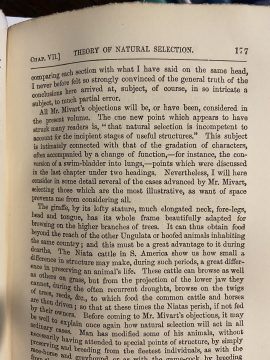

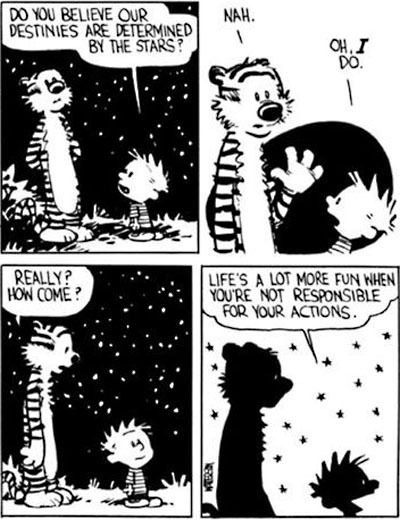

Sughra Raza. Untitled; Arnold Arboretum, Boston, March, 2020. The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy):

The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy): What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher