by Eric Miller

My father had an immensely fat friend whom I often glimpsed filling a plate alone at the buffet table of the King Eddie’s restaurant as I walked past that grand hotel. This man himself had a father even then in those days a nonagenarian, whom he saw daily, devotedly, taking him to the pool for a swim. It turned out that, obesity or no obesity, the friend would outlive my own father by twenty years. Because I liked the man very much, his longevity does not strike me as an injustice. He had a snuffling voice, small but piercing eyes, a gigantic nose and a fund of forgiving affection, the kind dispensed even in the awareness that what was being forgiven might have been awful. He preferred not to know, though his ignorance was (if I may venture a paradox) well informed. My mother played matchmaker for decades in his behalf, possibly because she found him appealing. Her stratagems did not avail. His marvellous acquitting heart remained unpaired.

My father had an immensely fat friend whom I often glimpsed filling a plate alone at the buffet table of the King Eddie’s restaurant as I walked past that grand hotel. This man himself had a father even then in those days a nonagenarian, whom he saw daily, devotedly, taking him to the pool for a swim. It turned out that, obesity or no obesity, the friend would outlive my own father by twenty years. Because I liked the man very much, his longevity does not strike me as an injustice. He had a snuffling voice, small but piercing eyes, a gigantic nose and a fund of forgiving affection, the kind dispensed even in the awareness that what was being forgiven might have been awful. He preferred not to know, though his ignorance was (if I may venture a paradox) well informed. My mother played matchmaker for decades in his behalf, possibly because she found him appealing. Her stratagems did not avail. His marvellous acquitting heart remained unpaired.

He was a developer though quite what he developed I never learned, except, I think, in the case of an undistinguished mall that replaced something approximately as without distinction. He partook of the spirit of Toronto, bulldozing the forgettable in order to raise aloft the unmemorable. He might have knocked down the old himself—never very old—just by walking forward with his characteristic look of merciless mercifulness. I praise him because of his energy. The moment in which I see him most vital is when he stands in the lot, in the wind-raked interval between demolition and construction. Lord of the pit and of the mullein that flowers for a time in the gash. Sometimes—despite his size and his wobbly ankles and his nice shoes—he would go on hikes with my father and my siblings out to the end of the Outer Harbour, this in the days before the spit was subject to manicuring and division among interested parties, the boaters and the sports enthusiasts and the rest, all eager to spoil what agreed with us, a total wasteland, entire dereliction. It may have pleased him to fancy that the debris of his excavations had contributed to the desert spaces where we all plodded in a wind that prevented conversation by grabbing words and dashing them out of reach like a shovel. Trucks may have tipped some of the rubbish of his enterprises into Lake Ontario, which would have stepped back in ambivalent recoil from the heavy donor, his heavier gift. Here was perpetuated on a colossal scale the pause after the jaws of the machinery have had their fill and before the logistics of raising a scaffold or pouring a foundation. All southwestern Ontario’s rejects, quisquiliae, scraps, reached into the midst of drastic cold waves that darkened by the winter minute. Read more »

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point.

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point. I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

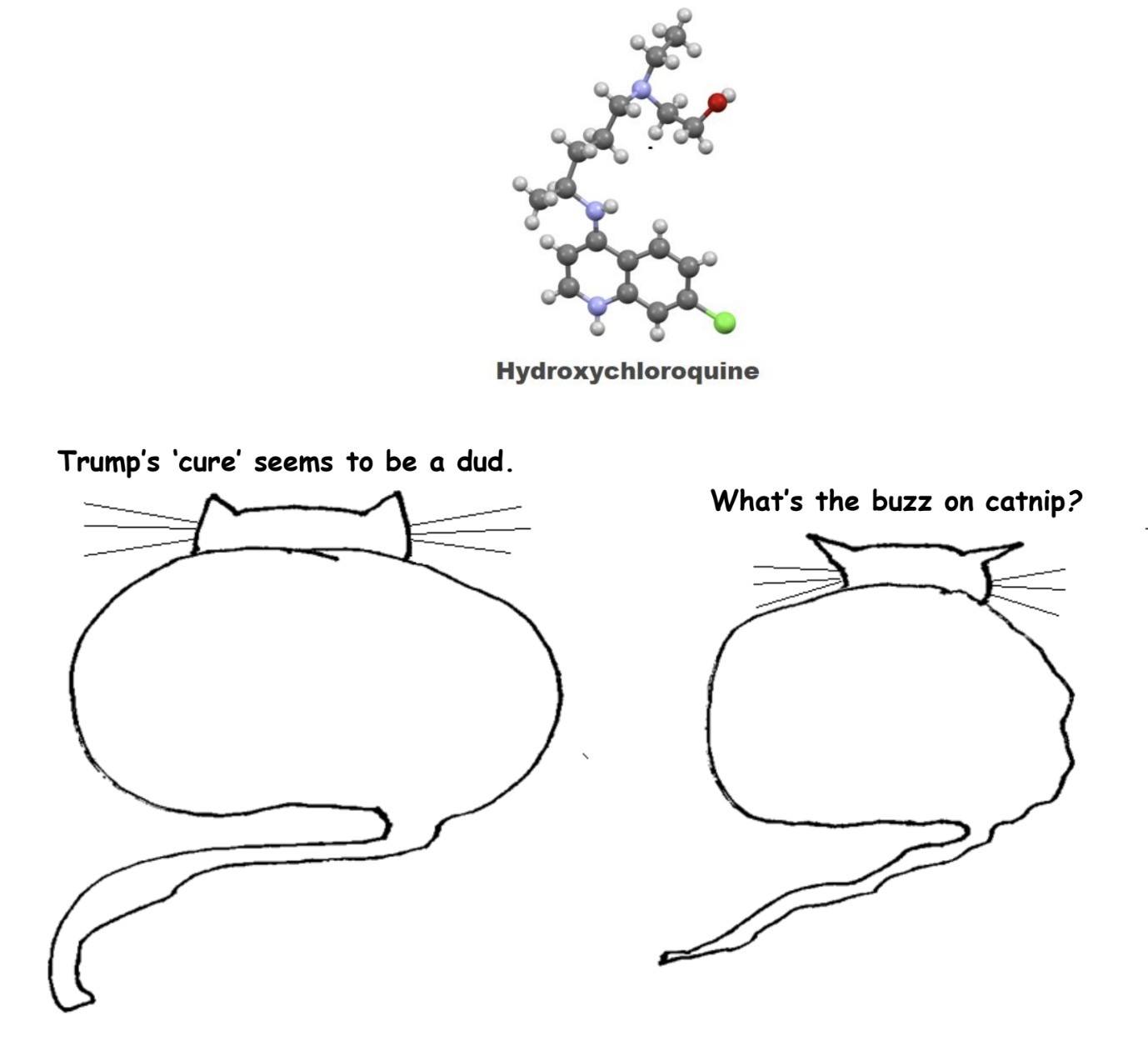

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that  Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).