by John Hartley

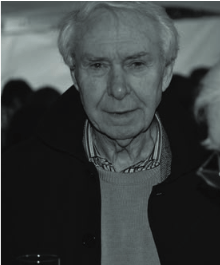

One wet January I happened to attend a meeting of the Newman Association – a Catholic group concerned with ecumenism. Long tailbacks on the motorway meant the guest speaker, making his way from Birmingham, was delayed. When Archbishop Bernard finally appeared an hour later, I was deep in conversation with my neighbour, a slightly built octogenarian with dishevelled white hair and a brown blazer.

David Ieuan Lloyd, I learnt, had studied and taught alongside Rush Rhees, Peter Winch and R F Holland, Howard Mounce and D Z Phillips, Dick Beardsmore and David Cockburn, in what was known as the ‘Swansea school’. The Philosophy department of Swansea University first cropped up on my radar some years earlier, when İlham Dilman’s treatise on Free Will singlehandedly side-tracked my undergraduate dissertation!

“Yes, I knew İlham well,” Ieuan reflected.

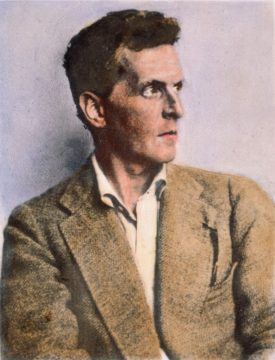

“What’s the big deal with Wittgenstein,” I finally asked, “It just seems like a load of nonsense!”

Ieuan gave a wry smile and what followed led to a series of semi-regular coffee shop conversations. Our inaugural meeting was a Pandora’s Box of maxims, rabbit holes and tangents, of which Ieuan later reflected “I hope the time today was of some use. I wondered when walking back that I stayed too long on the scepticism matter. More positively, would it be an idea when we next meet that you write a short menu on what you would like to discuss.”

Over the course of eighteen months I came to understand something of the ‘Swansea School’, from the many second-hand stories of someone who lived and breathed it, long after its cessation. Ieuan once recalled a story Rush Rhees had told.

“During a walk one day in Gower, Wittgenstein and Rhees encountered a bird writhing on the roadside, having been struck by a car.”

It brought to mind the scene of a dying bird in Terrence Malik’s film ‘The Thin red line’:

“One man looks at a dying bird and thinks there’s nothing but unanswered pain… Another man sees that same bird, feels the glory, feels something smilin’ through it.”

“What would Wittgenstein do?” I wondered.

Ieuan gave his customary wry smile and turned the conversation to philosophy of education, and Birmingham University, where he had finished his career. A stalwart defender of the confessional approach to teaching, Ieaun recalled how he had devised a new method of teaching physiotherapy. He published sparsely – chapters in books and odd journal articles – of which one poignantly addressed the question of how courage can be taught. When teaching ethics, example isn’t the main thing, it’s the only thing.

“But can it be taught?” I would say.

‘Courage’ in the context of teaching virtue was a recurring theme for Ieuan, who was deeply impacted by his lifelong friend, the Anglican Franciscan monk and later hermit, Father Ramon, for whom he would later deliver a eulogy at Worcester cathedral. Conversation spanned crime and punishment, justice, and whether forgiveness could ever be unconditional.

“Can proponents of capital punishment ever get what they want?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“If death can’t be lived through,” Ieuan replied, “then can we even call it a punishment at all?”

Open-ended questions like these would form the spine of endless hours of conversation; God and the nature of human existence, death and immortality, freedom and necessity. There was a sparkle in his eye when I recited the work of his dear friends and colleagues of the Swansea school. While DZ was undoubtedly the leader of the group, Ieuan spoke of J R Jones, “unsophisticated, simple and innocent,” and his treatise, “Love as the perception of meaning.” Of all his esteemed colleagues, it seemed that it was Jones who had left the greatest impression.

In order to structure out conversations, and guided by my interest in aesthetics, Lloyd suggested we discuss Dick Beardsmore’s ‘Art and Morality’, a work he had recently coedited with John Haldane. As the debates intensified, Lloyd became more animated, and fellow diners would look up from their conversations to behold this octogenarian in mid flow.

“Can a robot play chess?” Ieuan would ask, before doubling down on his concept of ‘play’.

My octogenarian guide expounded Wittgenstein in a way only someone who had been immersed in the Swansea school could. He recalled the rigour of the department meetings he referred to as the ‘lion’s den’, where their drill sergeant Rhees would repeat the mantra, “what example were you thinking of?”

“Theory doesn’t exist, only the particulars. Reality lies in the example.” was Ieuan’s mantra, and to my scepticism he would reply, “anyway, what answer would satisfy you?”

Looking back over my notes from those meetings, I am grateful for Lloyds interpretation of Wittgenstein’s insights into language, that ‘ancient city’ where every assertion contains an assumption, and ‘meaning’ is used illicitly to signify. Could we have a language without prepositions? If we bear in mind the image which appears in the mind as the sound is uttered, then we are at the mercy of memory. Ieuan returned to the story of the injured bird.

“Wittgenstein saw nothing but unanswered pain; he put the injured bird out of its misery.”

“Rhees said he was glad Wittgenstein did it, even though he couldn’t have himself.”

“The sense of the world must lie outside the world,” Were Ieuan’s parting words, “because death is not an event, it can’t be lived through,” and shortly after, he passed away.