by Tim Sommers

There’s something wrong with the sentence, “This sentence is false.” Is it true or false? Well, if it’s true, then it’s false. But then if it’s false, it’s true. And so on. This is the simplest, most straightforward version of the “Liar’s Paradox”. It’s at least two thousand five hundred years old and well-known enough that you can buy the t-shirt on Amazon.com.

I’ve been thinking about the “Liar’s Paradox” lately, because I’m teaching an “Introduction to Philosophy” class on paradoxes (and writing a book) called “Life’s a Puzzle: Philosophy’s Greatest Paradoxes, Thought-Experiments, Counter-Intuitive Arguments, and Counter-Examples from AI to Zeno”. It starts with the “Liar’s Paradox” because it’s one of the oldest and most well-known, but also simplest and most daunting, of philosophical paradoxes. Some people think that while “puzzle” cases in philosophy are fun and showy, they are not where the real action is. I think every real philosophical puzzle is a window onto a mystery. And proposed solutions to that mystery are samples of the variety and possibilities of philosophy.

So, let’s start with this. Why is it called the “Liar’s Paradox”? Let’s go to the Christian Bible for that one, specifically, “St. Paul’s Letter to Titus” (Ch. 1, verses 12-14)

“They must be silenced, because they are disrupting whole households by teaching things they ought not to teach – and that for the sake of filthy lucre.12 One of Crete’s own prophets has said it: ‘Cretans are always liars, evil brutes, lazy gluttons.’13 This statement is true.14”

Verse 12 has philosophers dead to rights. We are disrupting whole households, teaching things we ought not to teach and – speaking for myself at least – it’s all about the filthy lucre (hence, the book). But verse 13 is what we want here. It has “Cretan’s own prophet” saying “Cretans are always liars.” Now, if that just means that all Cretans lie a lot, but not all the time, there’s no problem. But if it means that Cretans are always lying whenever they speak, given that this is asserted by a Cretan (read: liar), we have a paradox. This then is the primordial, liar’s version of the “Liar’s Paradox”. If that’s unclear you can simplify the liar’s version down to: “I am lying right now.” Read more »

Donald Trump’s presidency has generated a greater than normal interest in American politics, but not necessarily for the right reasons. How, people wondered, could such a poorly qualified candidate, and, as we have seen over the years, of equally poor calibre possibly become the President of the United States and leader of the ‘free’ world?

Donald Trump’s presidency has generated a greater than normal interest in American politics, but not necessarily for the right reasons. How, people wondered, could such a poorly qualified candidate, and, as we have seen over the years, of equally poor calibre possibly become the President of the United States and leader of the ‘free’ world?

Irish-Canadian author

Irish-Canadian author

In my earlier column, “

In my earlier column, “

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

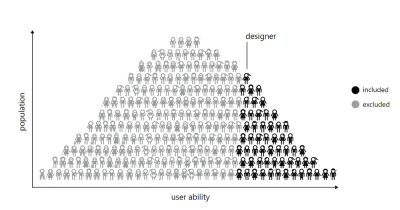

by Callum Watts

by Callum Watts