by Charlie Huenemann

I routinely remind my students that human minds have always been as complicated as they are now, from when we dropped out of the trees to when we step upon the escalator. When we are reading in the history of ideas there is always the temptation to turn intellectual landscapes into cartoons where options are limited, painted in bright primary colors, and uncomplicated, like a toddler maze in Legoland. What’s going on, I suppose, is some hidden supposition that people who lived in earlier times must have been like us when we were children; or to put it more accurately, we suppose that people of earlier times must have been like we now conceive ourselves to have been when we were children. For we are wrong on both counts. Our lives when we were children were more complicated than we now remember, and every life that has ever been lived has been more complicated than we are now likely to suppose, because that’s just what it is to be human: we are complication engines.

But it is also true that we know more than we have in the past. (That of course doesn’t make the minds of the past any less complicated: minds are not complicated by what they know, but by what they think they know). This is clearly true at the species level: humans know more now than they ever have before – Moon shots, penicillin, Higgs boson, and all that. But I am guessing that it is also true that we as individuals, on average, have more knowledge in our heads than our historical counterparts, on average. I have to guess this because how on earth could anyone know for sure that this is so? What would they measure? Whom would they measure? When would they measure it?

For what it’s worth, IQ scores have been going up since their inception (see the Flynn effect; though note that IQ scores seem to be hitting a plateau in recent times). But it stands to reason that if more people are getting more education, and if what people are being taught to some degree tracks what we, as a species, have come to know about the world, then more individuals should be gaining more knowledge than previously. Of course, this general truth – if it is a truth – falls apart as soon as we start complicating the discussion by asking what we are measuring as “knowledge”. So long as we stay at the unfocused level of “you know, truths about the world”, we can maybe get away with the general claim that individuals know more now than they have in the past.

But our advance in knowledge has come with an advance in the complexity of our problems. Read more »

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

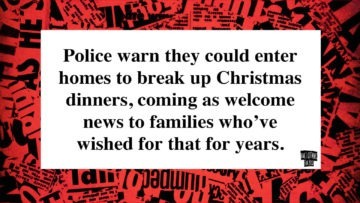

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.” Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class is a famous, influential, and rather peculiar book. Veblen (1857 – 1929) was a progressive-minded scholar who wrote about economics, social institutions, and culture. The Theory of the Leisure Class, which appeared in 1899, was the first of ten books that he published during his lifetime. It is the original source of the expression “conspicuous consumption,” was once required reading on many graduate syllabi, and parts of it are still regularly anthologized.

Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class is a famous, influential, and rather peculiar book. Veblen (1857 – 1929) was a progressive-minded scholar who wrote about economics, social institutions, and culture. The Theory of the Leisure Class, which appeared in 1899, was the first of ten books that he published during his lifetime. It is the original source of the expression “conspicuous consumption,” was once required reading on many graduate syllabi, and parts of it are still regularly anthologized.