by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

In his victory speech President-elect Joe Biden declared that “this is the time to heal America,” urging citizens to “come together,” “give each other a chance,” and “stop treating opponents as enemies.” He added that partisanship “is not due to some mysterious force,” but is rather “a choice we make.” To be sure, that partisanship is a choice doesn’t mean it’s easily overcome. So, Biden offered a plan. He proposed that we “see each other again” and “listen to each other again.”

In calling for the healing of our partisan divisions, Biden struck a popular note. Americans across the spectrum tend to agree that our politics has become dangerously toxic and uncivil. We say we want more compromise, civility, and cooperation in politics; however, it seems we demand that compromise come strictly from our political opponents. Oddly, lamenting partisan division is itself an expression of our animosity towards the other side. That is, the distance we see between ourselves and our political others is perceived as their distance from our ideas, their resistance and recalcitrance to our thoughts. Consequently, even though Republican and Democratic citizens generally are no more divided over central public policy issues than they were forty years ago, we are more partisan than ever in that we are more inclined to regard our partisan opponents as untrustworthy, dishonest, unpatriotic, and threatening.

In other words, partisan division is a matter of our negative feelings towards the other side, rather than disagreements over political ideas. Perhaps unsurprisingly, citizens’ political behavior – voting, donating, volunteering, and so on – is now more driven by animosity for the opposing party than by commitment to the ideals of our own.

This animosity is tied to a range of phenomena which have rendered our partisan identities central to our overall self-understandings. In the United States, liberalism and conservatism are distinct lifestyles, with partisan identity serving as the “hyper-identity” that organizes all of the other aspects of our lives, from our consumption habits to our religious affiliations and views about family and child-rearing. As we grow to see our partisan rivals as living strange lives that differ from our own, we come eventually to see their lives as alien and eventually degenerate. Seeing them in this way, we project on to them exaggerated vices, including close-mindedness, untrustworthiness, lack of patriotism, dishonesty, and general immortality. From there, we then infer a vast divide over democracy itself, with no common ground or basis for cooperation. What is shared government with those who appear to be moral aliens?

Biden’s recipe for political healing is thus fraught. Read more »

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic. A Task for the Left

A Task for the Left

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon. In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

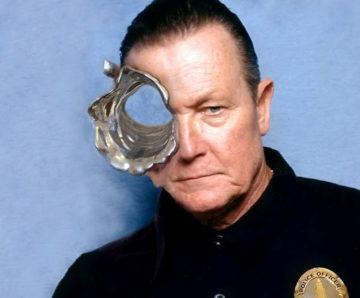

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow. One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

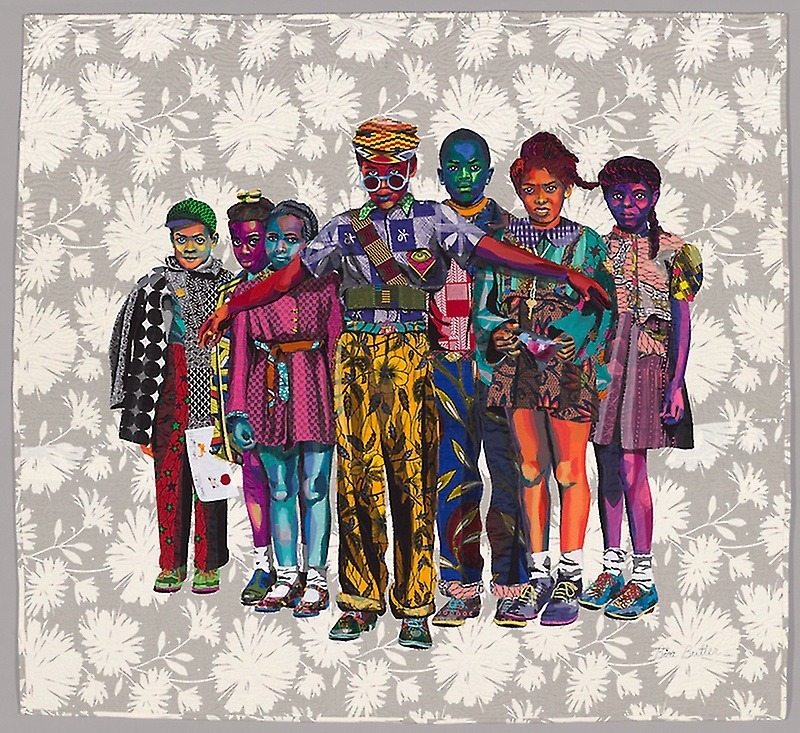

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.