by Varun Gauri

An autocratic president, whom the opposition blames for thousands of deaths, faces a referendum on his rule. The majority rejects him in the election, but around 45% vote for him to remain in office. The would-be permanent dictator begrudgingly departs, yet he retains a fanatically loyal following, especially among the religious right, some business leaders, the security establishment, and voters scared of socialism. Conservative politicians and radical rightists fear his influence, permitting him and his acolytes to remain powerful voices in national politics for many years. That hold on the political right, alongside structural impediments in the national constitution, the opinions of the judges he appointed, and the continuity in office of his regime functionaries make it is impossible for the country to address social and economic inequality and consolidate democratic reform.

A forecast of the United States post-Trump? Perhaps.

A description of Chile post-Pinochet? Definitely.

This year, thirty-one years after Pinochet left office, fifteen years after he died, Chile will hold elections for a constitutional convention to replace the military Constitution of 1980, even though the government is led by a president whose rightist party once supported Pinochet. Following the latest in a series of student-led protests, the country may at last have moved on from “moving on,” now aiming to redress inequality and entrench democracy more deeply in its political institutions.

What took so long? Read more »

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

The presence of covid-19 running amok amongst us has momentarily disrupted the perimeters of our lives. That two, three, or possibly four generations are not always able to gather together under one roof has given rise to greater appreciation of the family.

The presence of covid-19 running amok amongst us has momentarily disrupted the perimeters of our lives. That two, three, or possibly four generations are not always able to gather together under one roof has given rise to greater appreciation of the family.

1. “A more perfect union.” The Founders expressed a breezy confidence, didn’t they? As if such a thing were possible – the distant states cohered into a nation; the various occupants working it all out. Loyal. Collaborative. Taking part in the common welfare. While remaining, of course, individual and autonomous and free, free, free. (Certain restrictions applied.)

1. “A more perfect union.” The Founders expressed a breezy confidence, didn’t they? As if such a thing were possible – the distant states cohered into a nation; the various occupants working it all out. Loyal. Collaborative. Taking part in the common welfare. While remaining, of course, individual and autonomous and free, free, free. (Certain restrictions applied.)

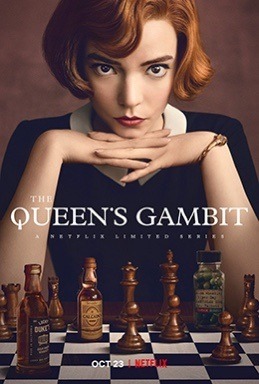

Two series have been streaming recently, to considerable success – The Queen’s Gambit (a Netflix miniseries, now concluded) and Succession (HBO, two series so far and more planned). They are interesting for a number of reasons – both for what they show, and perhaps more for what they do not, possibly cannot, show. So let’s consider some of the things we see and don’t see. I’m not going to recount the plot of either of them, as you can get that from Wikipedia and plenty of other places. But: spoiler alert: some will be divulged. Let’s look first at The Queen’s Gambit.

Two series have been streaming recently, to considerable success – The Queen’s Gambit (a Netflix miniseries, now concluded) and Succession (HBO, two series so far and more planned). They are interesting for a number of reasons – both for what they show, and perhaps more for what they do not, possibly cannot, show. So let’s consider some of the things we see and don’t see. I’m not going to recount the plot of either of them, as you can get that from Wikipedia and plenty of other places. But: spoiler alert: some will be divulged. Let’s look first at The Queen’s Gambit.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.