by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Deep disagreements are disagreements where two sides agree on so little that there are no shared resources for reasoned resolution. In some cases, argument itself is impossible. The fewer shared facts or means for identifying them, the deeper the disagreement.

Some hold that many disagreements are deep in this way. They contend that reasoned argument has very little role to play in discussions of the things that divide us. Call these the deep disagreement pessimists – they claim that many of the disputes we face cannot be addressed by shared reasoning.

There are also deep disagreement optimists. Their view is that deep disagreements are intractable only for contingent reasons – perhaps we have not yet surveyed all the available evidence, or we are waiting on new evidence, or there is some background shared methodological principle yet to be uncovered. With deep disagreement, the optimist holds, it is hasty to give up on rational exchange, because something useful is likely available, and the costs of passing such rational resolution up are too high. Better to keep the critical conversation going.

Disputes among pessimists and optimists regularly turn on the practical question: Are there actual deep disagreements? The debates over abortion and affirmative action were initially taken to be exemplary of disagreements that are, indeed, deep. Later, secularist and theists outlooks on the norms of life were taken to instantiate a divide of the requisite depth. More recently, conspiracy theories have been posed as points of view at deep odds with mainstream thought.

This brings us to QAnon. Read more »

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

The presence of covid-19 running amok amongst us has momentarily disrupted the perimeters of our lives. That two, three, or possibly four generations are not always able to gather together under one roof has given rise to greater appreciation of the family.

The presence of covid-19 running amok amongst us has momentarily disrupted the perimeters of our lives. That two, three, or possibly four generations are not always able to gather together under one roof has given rise to greater appreciation of the family.

1. “A more perfect union.” The Founders expressed a breezy confidence, didn’t they? As if such a thing were possible – the distant states cohered into a nation; the various occupants working it all out. Loyal. Collaborative. Taking part in the common welfare. While remaining, of course, individual and autonomous and free, free, free. (Certain restrictions applied.)

1. “A more perfect union.” The Founders expressed a breezy confidence, didn’t they? As if such a thing were possible – the distant states cohered into a nation; the various occupants working it all out. Loyal. Collaborative. Taking part in the common welfare. While remaining, of course, individual and autonomous and free, free, free. (Certain restrictions applied.)

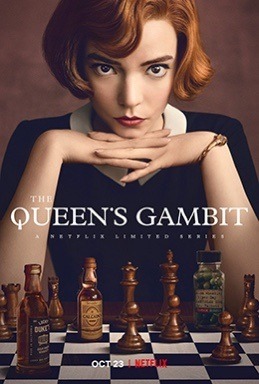

Two series have been streaming recently, to considerable success – The Queen’s Gambit (a Netflix miniseries, now concluded) and Succession (HBO, two series so far and more planned). They are interesting for a number of reasons – both for what they show, and perhaps more for what they do not, possibly cannot, show. So let’s consider some of the things we see and don’t see. I’m not going to recount the plot of either of them, as you can get that from Wikipedia and plenty of other places. But: spoiler alert: some will be divulged. Let’s look first at The Queen’s Gambit.

Two series have been streaming recently, to considerable success – The Queen’s Gambit (a Netflix miniseries, now concluded) and Succession (HBO, two series so far and more planned). They are interesting for a number of reasons – both for what they show, and perhaps more for what they do not, possibly cannot, show. So let’s consider some of the things we see and don’t see. I’m not going to recount the plot of either of them, as you can get that from Wikipedia and plenty of other places. But: spoiler alert: some will be divulged. Let’s look first at The Queen’s Gambit.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.