by Brooks Riley

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned?

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned?

This is the paradox of the pandemic: Lockdown has sent many of us on the wildest of journeys—not to a different place, but to a different self, even if such a destination is temporary.

What if a consequence of going nowhere and doing nothing for a year is finding out there’s a stranger living inside you? Unlike yourself these days, the stranger isn’t in isolation. It goes everywhere you can’t, especially down rabbit holes where the ‘you’ you think you know would never go. Uninvited, this stranger is no guest, it’s just been squatting in your brain until the time was right.

Don’t confuse the stranger with an inner voice. The stranger doesn’t chat or chatter. It’s not interested in your opinions, nor does it want to convince you of something, or help you ‘harness’ an inner anything. Its agenda is to hold you hostage, no questions taken, no answers given.

I’m unclear as to the stranger’s gender. Is it a girl, a middle-aged man, a woman, an old lady, a boy? Does it matter now that the stranger lives in the part of yourself that once indulged in its own peregrinations?

When you weren’t looking, it pulled up a chair next to you and grabbed the mouse, that most direct instrument of intent, and began to map out a new itinerary. It’s become harder not to notice as it steers your ship of self away from its charted course and into unknown territory. An interloper in your command central, the stranger now begins to assert itself, to exert its will in appalling ways–mostly having to do with music. Read more »

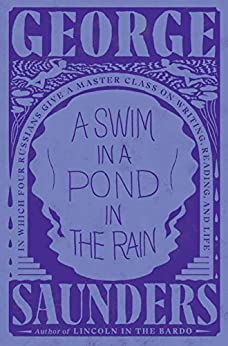

In the part of my life when I was most actively trying to invent myself as a writer, I was working as a high school teacher and was desperately unhappy. (Notice the way that I put this: “I was working as a high school teacher,” not “I was a high school teacher”; the notion that a job defines a person still disgusts me.) In the evenings, I left work and wrote magazine pitches, not as many, I realize in retrospect, as could have brought me success, but enough to keep me talkative in the teacher’s lounge. I had the impression, back then, that a writer could make a name for himself on the basis of a single strong piece, and since my work was deeply derivative—I was, after all, inexperienced—I hatched a plan.

In the part of my life when I was most actively trying to invent myself as a writer, I was working as a high school teacher and was desperately unhappy. (Notice the way that I put this: “I was working as a high school teacher,” not “I was a high school teacher”; the notion that a job defines a person still disgusts me.) In the evenings, I left work and wrote magazine pitches, not as many, I realize in retrospect, as could have brought me success, but enough to keep me talkative in the teacher’s lounge. I had the impression, back then, that a writer could make a name for himself on the basis of a single strong piece, and since my work was deeply derivative—I was, after all, inexperienced—I hatched a plan.

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture.

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “