by Joseph Shieber

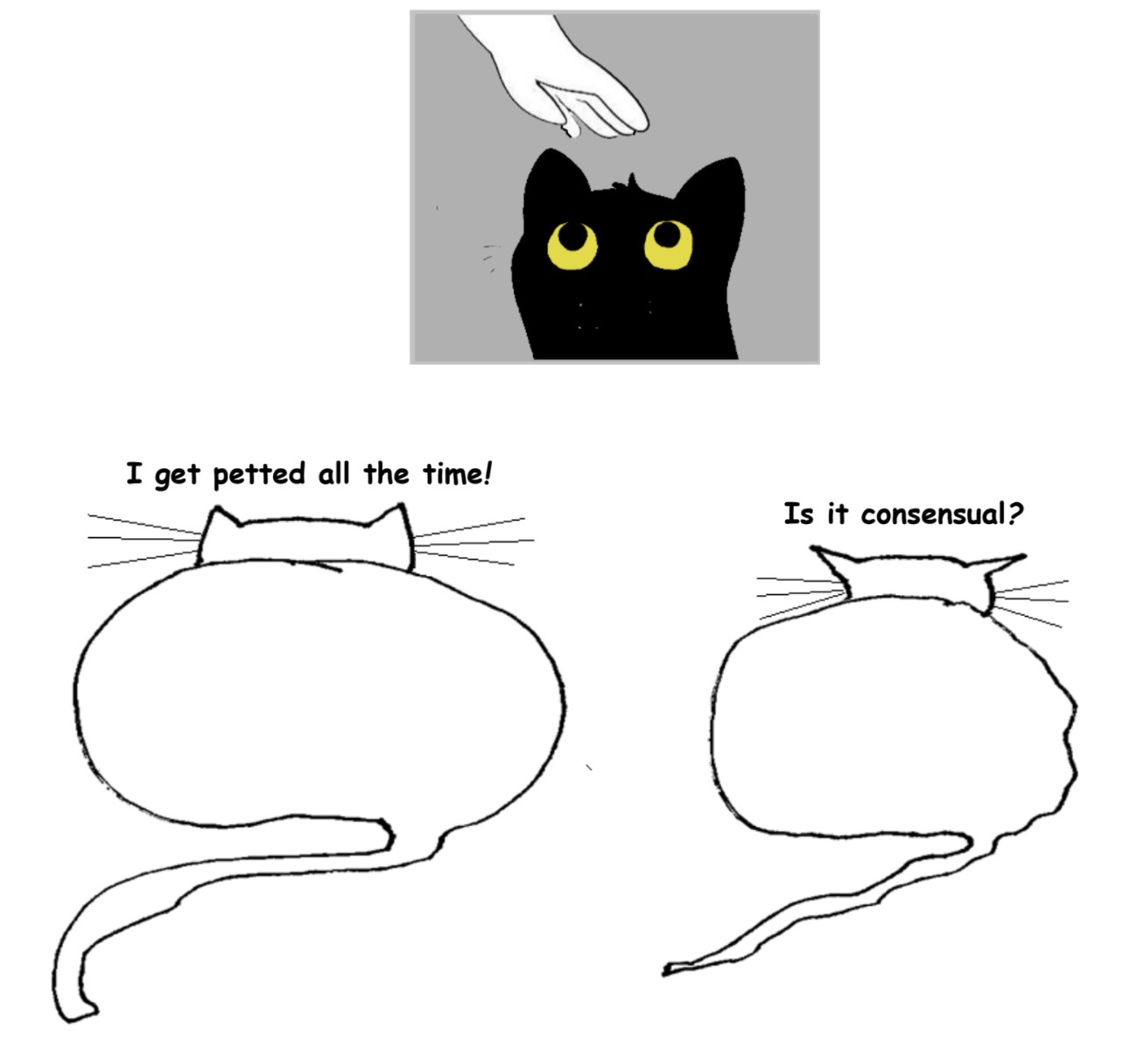

One of the most highly publicized philosophy papers of the 2000s was a paper that was actually written almost two decades earlier. Harry Frankfurt’s paper “On Bullshit” was first published in 1986, but some astute editor at Princeton University Press, noting its aptness for the George W. Bush era, reprinted the paper as a slim book.

The effect was electric. Frankfurt’s essay appeared in January of 2005 and was on the New York Times bestseller list for almost half of the year. Among Frankfurt’s many media appearances was a notable interview on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart about the book’s subject matter and its unexpected success (success so surprising that the Daily Show also interviewed a representative of Princeton University Press to discuss it).

According to Frankfurt’s discussion, “bullshit” refers to intentionally misleading communication in which “the bullshitter hides … that the truth-values of his statements are of no central interest to him; what we are not to understand is that his intention is neither to report the truth nor to conceal it. … the motive guiding and controlling it is unconcerned with how the things about which he speaks truly are.” Read more »

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

Covid has

Covid has  One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!—

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!— In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”

In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”