by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

The other times I used to go to the post office was to mail my grandmothers’ frequent letters, which she had dictated to me the previous day. She was a marvelous cook, spent long hours in the kitchen despite her osteoarthritic stoop, and then after everybody has been fed, she’d sit down in the kitchen with her own food and call me to take the dictation of her letters. She was not illiterate, but she liked my ways of phrasing in an organized way the outpouring of her emotions and frustrations in those letters to her near ones. My skill at concise expressions of intense personal feelings, honed in my grandmother’s kitchen, was later tested once in a crowded Kolkata post office. There an illiterate migrant worker from a Bihar village approached me for filling the money-order form that he required for remitting a meager amount of money to his family back at the village. When it came to filling the measly little space at the end of the form where you are allowed to send a brief message, this worn-out man sat on the floor on his haunches and told me what to write there in sporadic bursts of raw emotion (an incoherent mixture of his affection, anxiousness, and longing) for his daughter and wife in the village whom he has not seen for many months, and my skill was sorely tested, and I think I failed, particularly because the language had to be Hindi, in which I was deficient. Read more »

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

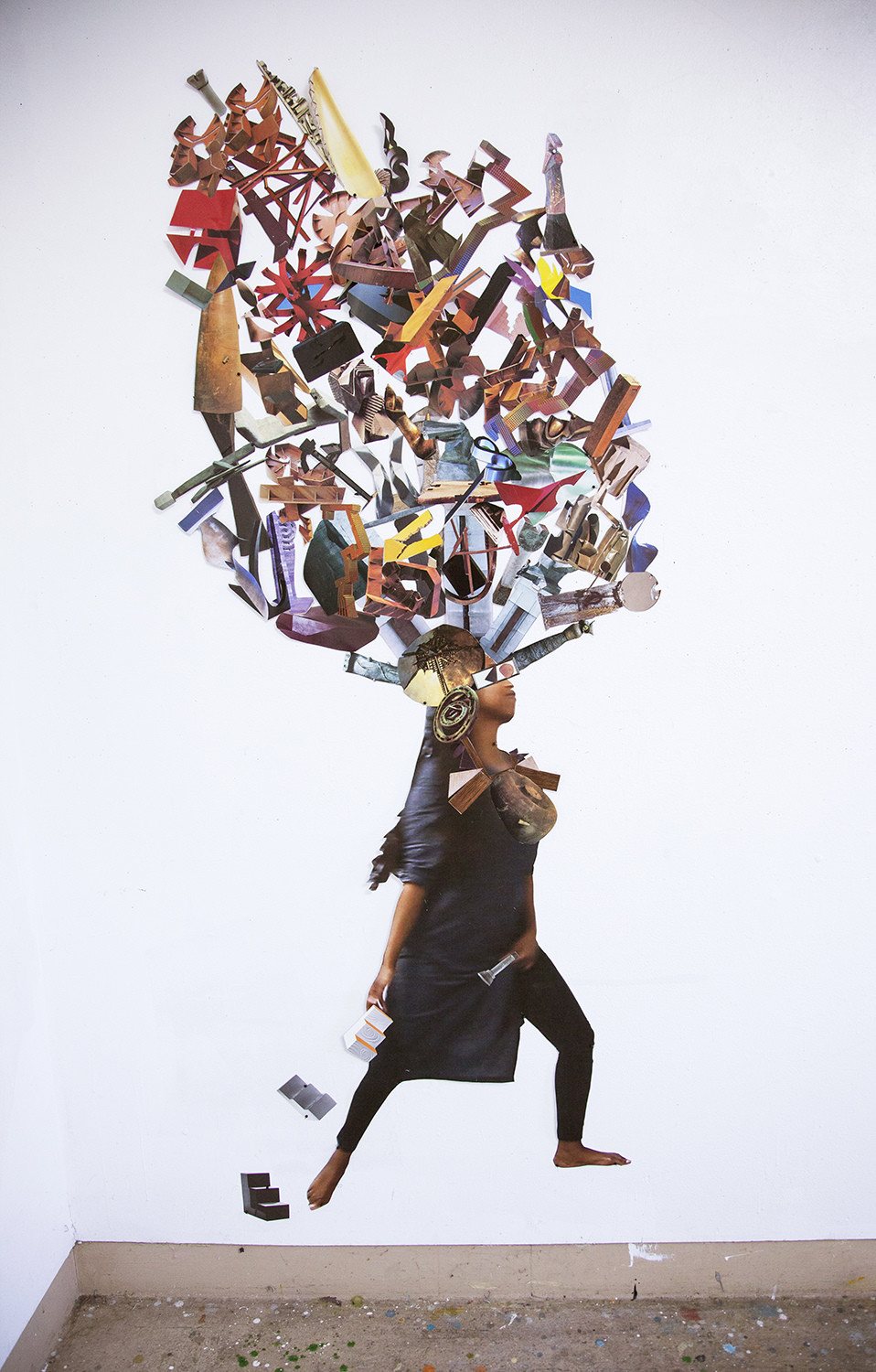

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this? The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also. The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

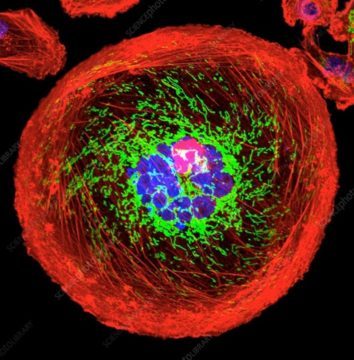

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the

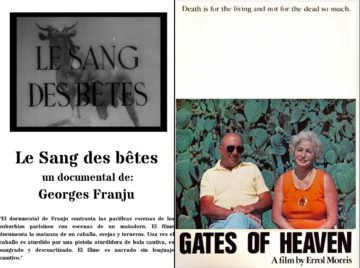

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

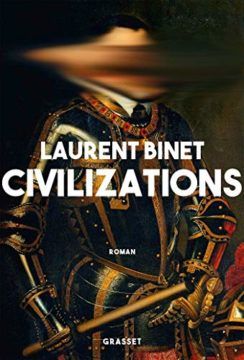

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.