by Mark Harvey

Here’s a weird thought: if it weren’t for 18th-century vaccines, America might have lost the revolutionary war to the British. That would have meant that all the anti-vaxxers today touting their freedom not to get a vaccine might have inherited quite a different destiny of eating scones and clotted cream under the British crown. Viruses have always been with us and they always will be, but in the early days of the revolutionary war, an invisible enemy probably killed more American soldiers than the British did. That quiet killer with no generals, no cannon, no forts, and no muskets was smallpox. The weapon against smallpox back then wasn’t truly a vaccine, for modern vaccines hadn’t been invented. But the inoculations were based on a similar principle of introducing a pathogen into a human to develop immunity to a disease.

It’s hard to know exactly how long smallpox has been with us, but we do know that it has been around for at least a few thousand years and probably killed Pharaoh Ramses V in 1157 B.C. When archaeologists unwrapped the linens and layers of resin preserving the pharaoh, his skin showed the characteristic pockmarks of a bad case of smallpox.

George Washington himself had suffered a bout of smallpox when he was traveling with his brother through Barbados at the age of 19. The illness incapacitated him for a solid month but also left him with a lifelong immunity, and a respect and understanding of the disease that would come to play a huge role in the revolutionary war and even the destiny of our country. Read more »

In spite of my abiding interest in literature when I came to college I was vaguely inclined to major in History. In the long break between school and college I chanced upon two books of Marxist history which opened me to a new vista of looking at history. The first was Maurice Dobb’s Studies in the Development of Capitalism. This book showed me that there is a discernible pattern in the jumble of facts in history, which attracted me. Soon after, I read a lesser Marxist history book, A.L. Morton’s People’s History of England which showed me how recasting the old widely-known history of England from the people’s perspective gives you new insights. These books whetted my appetite to read more of Marxist history.

In spite of my abiding interest in literature when I came to college I was vaguely inclined to major in History. In the long break between school and college I chanced upon two books of Marxist history which opened me to a new vista of looking at history. The first was Maurice Dobb’s Studies in the Development of Capitalism. This book showed me that there is a discernible pattern in the jumble of facts in history, which attracted me. Soon after, I read a lesser Marxist history book, A.L. Morton’s People’s History of England which showed me how recasting the old widely-known history of England from the people’s perspective gives you new insights. These books whetted my appetite to read more of Marxist history. The events in Afghanistan over the last week are being seen as yet another “hinge moment” in history. The images of helicopters evacuating personnel from embassies and people chasing aircraft in desperation to get on them have been seared into the memories of all who have seen them. As a person from the region (Pakistan), a student of history, and as someone interested in the current state of the world, I too have watched these events with a mixture of amazement, trepidation, horror, and perplexity. It is not clear yet whether “hope” or “fear” – or both – should be added to that list. The things I say in this piece are just the thoughts and speculations of a non-expert lay person trying to make sense of an obscure situation. As will be obvious from the rest of this piece, for all the pain and suffering the new situation in Afghanistan will bring to people in Afghanistan, I think that the American decision to withdraw was the only rational choice. The alternative of staying on for years – perhaps decades – to build a better Afghanistan would just be another exercise in paternalistic colonialism. However, the way the withdrawal is happening is a great failure of American leadership and the blame for that lies mainly with the American policies of the last two decades. Perhaps its biggest failure was in not preparing Afghanistan for this day that was sure to come sooner or later. Now the Afghan people – especially women – will pay a price for that failure, but it may also come back to haunt the United States and other great powers. It has happened before….

The events in Afghanistan over the last week are being seen as yet another “hinge moment” in history. The images of helicopters evacuating personnel from embassies and people chasing aircraft in desperation to get on them have been seared into the memories of all who have seen them. As a person from the region (Pakistan), a student of history, and as someone interested in the current state of the world, I too have watched these events with a mixture of amazement, trepidation, horror, and perplexity. It is not clear yet whether “hope” or “fear” – or both – should be added to that list. The things I say in this piece are just the thoughts and speculations of a non-expert lay person trying to make sense of an obscure situation. As will be obvious from the rest of this piece, for all the pain and suffering the new situation in Afghanistan will bring to people in Afghanistan, I think that the American decision to withdraw was the only rational choice. The alternative of staying on for years – perhaps decades – to build a better Afghanistan would just be another exercise in paternalistic colonialism. However, the way the withdrawal is happening is a great failure of American leadership and the blame for that lies mainly with the American policies of the last two decades. Perhaps its biggest failure was in not preparing Afghanistan for this day that was sure to come sooner or later. Now the Afghan people – especially women – will pay a price for that failure, but it may also come back to haunt the United States and other great powers. It has happened before….

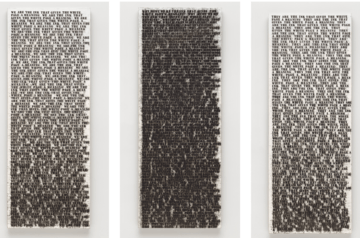

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market