by Eric J. Weiner

He was both a street fighter and a hard-boiled romantic for whom the radical imagination was at the heart of a politics that mattered, and he was one of few great intellectuals I knew who took education seriously as a political endeavor. —Henry Giroux

On August 16, 2021, Stanley Aronowitz, Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Urban Education at the Graduate Center of City University of New York, labor organizer, educational theorist, author, and dissident public intellectual died. Essentially self-educated, he told me once that he began with Spinoza and just kept reading. He may have actually started with Kafka or Dostoevsky, but the order of things is less important than the central lesson. It’s because of him that I often find myself telling my students—who overwhelmingly come to Montclair State University for a credential or, in Aronowitz’s lexicon, to be “schooled”—that to be educated all they really need is a “library card” and intellectual curiosity.

Through his radical and relentless pursuit of knowledge and justice, Aronowitz provided a blueprint for living an intellectual life that matters to those of us who refuse to accept the status quo. He showed us through his dissident research and activism how to direct the imagination toward the utopic horizon of radical democratic freedom and economic justice. At the heart of Stanley’s intellectual project was his life-long rejection of fatalism; his revealing criticisms of the status quo always pointed to radical possibilities for social change. Aronowitz never feared freedom like so many “intellectuals” who camouflage their conservative bias within critiques overburdened by cynicism. His embrace of what Erich Fromm called “positive freedom” was amplified by his deep respect for working people and his willingness to get his hands dirty in the fight for a future that looked radically different than the past or present. Read more »

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face?

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face? When Robert Solow asked me in Cambridge if I’d like to join the faculty at MIT in the other Cambridge, I was taken aback, and asked for some time to think about it. Until then I never imagined living in the US, a country I had never visited before, and what I saw in Hollywood films was not always attractive. I was planning to go back to India where my aging parents, younger siblings, and the majority of my friends were.

When Robert Solow asked me in Cambridge if I’d like to join the faculty at MIT in the other Cambridge, I was taken aback, and asked for some time to think about it. Until then I never imagined living in the US, a country I had never visited before, and what I saw in Hollywood films was not always attractive. I was planning to go back to India where my aging parents, younger siblings, and the majority of my friends were.

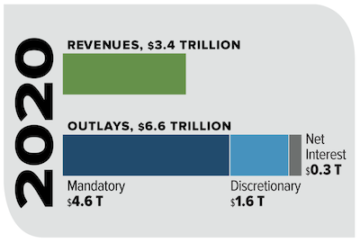

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide.

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide. Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”

Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”  Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Clairvoyant of the Small, Susan Bernofsky’s long-awaited biography of the Swiss modernist writer Robert Walser, is erudite, painstakingly thorough, and sensitively written. Readers of Walser finally have a volume that connects the development of the writer’s work and its publishing history to the various episodes of his peripatetic adult life in the cities of Biel, Bern, Zurich, Berlin, and finally the sanatoriums in Waldau and later Herisau, where Walser—revered by Franz Kafka and Max Brod, Walter Benjamin, W. G. Sebald, and many others—presumably ceased writing altogether.

Clairvoyant of the Small, Susan Bernofsky’s long-awaited biography of the Swiss modernist writer Robert Walser, is erudite, painstakingly thorough, and sensitively written. Readers of Walser finally have a volume that connects the development of the writer’s work and its publishing history to the various episodes of his peripatetic adult life in the cities of Biel, Bern, Zurich, Berlin, and finally the sanatoriums in Waldau and later Herisau, where Walser—revered by Franz Kafka and Max Brod, Walter Benjamin, W. G. Sebald, and many others—presumably ceased writing altogether.

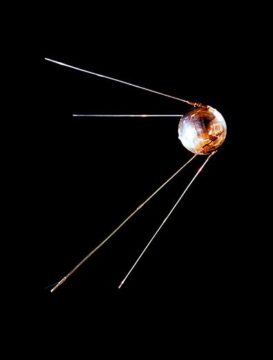

Men have always wanted to fly to the moon and stars. We wanted to find out what was up there on the moon and planets? Was it heaven? Were there angels? Or were these worlds inhabited by strange creatures who built canals? We looked up, we used telescopes. We watched the stars and charted their movements. But we wanted to do more than look and imagine; we wanted to go up there and see for ourselves? The birds could fly, why couldn’t we?

Men have always wanted to fly to the moon and stars. We wanted to find out what was up there on the moon and planets? Was it heaven? Were there angels? Or were these worlds inhabited by strange creatures who built canals? We looked up, we used telescopes. We watched the stars and charted their movements. But we wanted to do more than look and imagine; we wanted to go up there and see for ourselves? The birds could fly, why couldn’t we?

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.