by Sarah Firisen

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

My now ex-husband and I were very into Second Life around 14 years ago. Quickly, we realized an essential truth about the virtual world: much like the real world, it gets boring very fast without some kind of purpose. Yes, there was the initial amusement of learning how Second Life worked. We learned how to change our clothes, body shape, and hair. We learned how to control our avatars so we could fly. That was fun. We met a few people and made some friends. I’ve written before about the very real friendships that I made in my virtual life. But after a few weeks, we needed more. My ex had always been very interested in ancient Rome. He found an ancient Roman sim (themed digital plots of land), ROMA, and became involved with the community. He bought a toga and eventually became a senator. A real-life archaeologist created the sim, and it attracted a large group of ancient history buffs. They enthusiastically took on role-playing from the senate to gladiators to high priestesses at one of the temples. When I checked into ROMA for this piece, it seems like the sim still exists and has an active community.

U.S. dollars could be traded for the in-world Linden currency, and Second Life had a vibrant economy. Virtual commerce was wide-ranging, from new hairstyles to clothes to waterslides. But if you were so inclined, everything and anything in Second Life was buildable by users. Manipulating basic shapes and adding colors and textures, it was possible to create anything that an avatar could desire. A scripting language could be attached to the objects in the same way that Javascript can be attached to HTML objects. Back then, I was a software developer and became fascinated with building and scripting. But I needed a purpose to my building. So I started making clothes for myself and then started selling them. To do that, I required stores in which to sell my clothes and scripts to enable people to buy my outfits. Before I knew it, Fashion by B was a serious hobby. Read more »

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

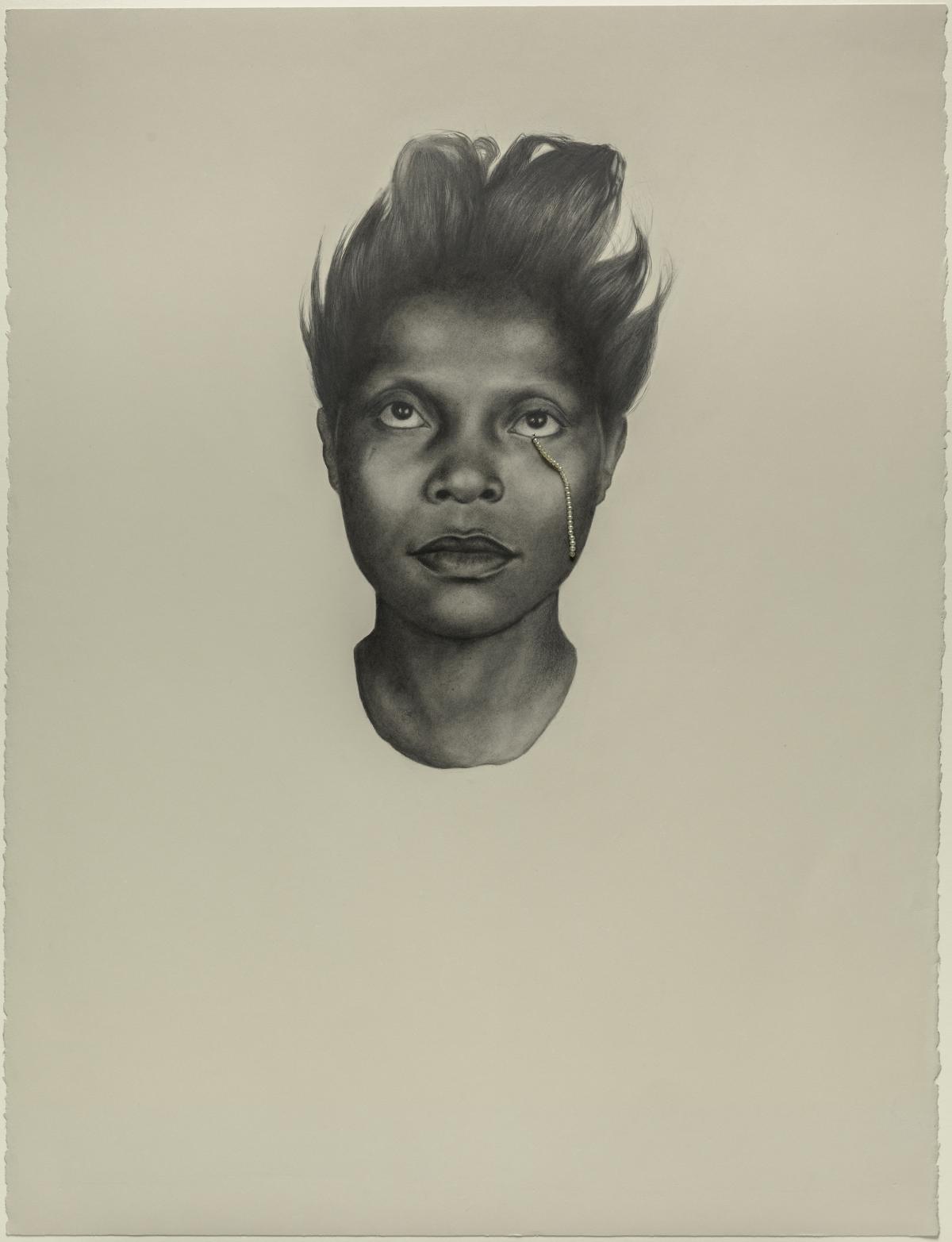

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011.

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011. Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies.

Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies. We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth. A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise?

A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise?