by Joseph Shieber

One of the most famous philosophical arguments is Pascal’s Wager, an attempt by the 17th century French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal to provide ammunition for religious believers in their struggles against nonbelief.

The Wager works like this. First, there are two possible states of affairs that you’re to consider: either God exists or God doesn’t exist. Second, there are two possible attitudes you could adopt with respect to God’s existence: either you believe that God exists or you don’t believe that God exists (you either actively believe that God doesn’t exist or you withhold belief in God’s existence.

This gives us the following possible combinations, with their resultant outcomes:

- You believe & God exists: eternal bliss in heaven

- You believe & God doesn’t exist: one false belief

- You don’t believe & God doesn’t exist: one true belief (at best)

- You don’t believe & God exists: eternal torment in hell

This way of setting out the case for belief vs. nonbelief does not do the nonbeliever any favors.

If you don’t believe, the optimal result would be that God doesn’t exist. Then you would have one more true belief than the rubes who falsely believe (assuming of course that you actively disbelieve, rather than merely withholding belief in God’s existence). The other possibility for non-believers, however, is truly horrible. If you don’t believe and God DOES exist, then you are damned to an eternity of suffering in hell.

Contrast this with the situation for believers. The worst case for them is that they believe, but God doesn’t exist. Still not so bad! Just one additional false belief! If, however, God DOES exist, then the believer can look forward to a reward of eternal life in heaven.

Now, there are a variety of ways to object to the set-up of the Wager. Read more »

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams.

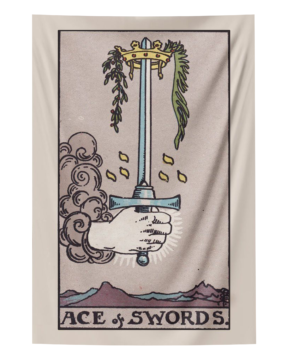

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams. When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

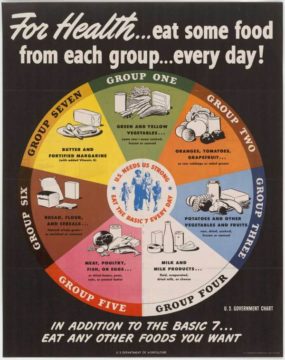

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament.

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament. Even though my ISI office was in the Planning Commission building in New Delhi I was living in an apartment complex far away in ‘Old’ Delhi, nearer Delhi University. The main attraction of staying there was the number of academic friends who lived in the same complex, apart from its being in a rather open, leafy, quieter part of the city (the hilly walkway at the back—called ‘the ridge’– was full of parrots and monkeys). My MIT friend, Mrinal, who stayed there arranged with the landlord for our accommodation.

Even though my ISI office was in the Planning Commission building in New Delhi I was living in an apartment complex far away in ‘Old’ Delhi, nearer Delhi University. The main attraction of staying there was the number of academic friends who lived in the same complex, apart from its being in a rather open, leafy, quieter part of the city (the hilly walkway at the back—called ‘the ridge’– was full of parrots and monkeys). My MIT friend, Mrinal, who stayed there arranged with the landlord for our accommodation. I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren.

I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren. Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing. The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,  Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.

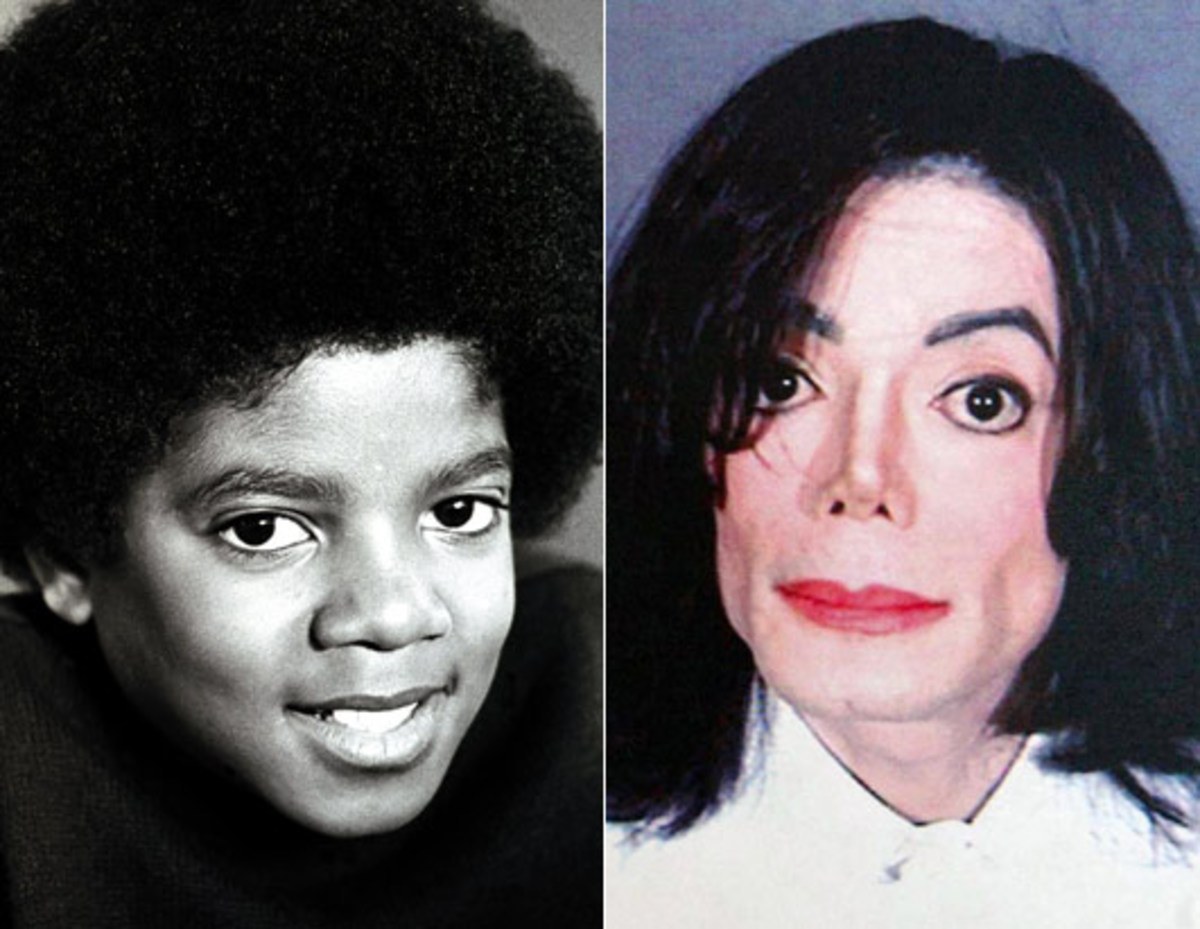

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021. Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

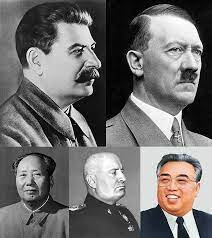

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.