by Chris Horner

Two Scenarios

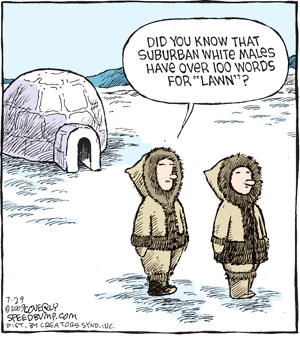

First scenario: you attempt to criticise, condemn or otherwise focus on an unjust regime, act of aggression, atrocity, or cruelty. An example: a school has been bombed and children have died. It is a war crime and you name it as such as an evil, criminal thing. Soon after the words leave your mouth, or get posted online, someone responds with something along these lines: yes, that’s all very well, but why just condemn that? What about..? They then name some other, maybe similar atrocity that you haven’t mentioned. The case you wanted to draw attention to is lost, displaced and deferred to other examples that your interlocutor claims you should be equally concerned about. This is what aboutism, and it can be quite annoying.

Second Scenario: someone criticises, condemns or otherwise focuses on an unjust regime, act of aggression, atrocity, cruelty. Let’s say a school has been bombed and children have died. It is a war crime and they name it as such, as an evil, criminal thing. But it is quite obvious to you that they are being selective in their outrage: they don’t seem to care about the times schools have been bombed in other places, by other militaries. Why just this example? So you point this out. All children matter, and not just the ones your interlocutor seems to care about. This is selective outrage, and it can be quite annoying, to put it mildly.

Clearly, one can find oneself on either side of this kind of exchange. One person’s demand for ethical or political consistency can be just a case of what aboutism to another. So is it just the effect of where one is positioned in an argument? Perhaps, but it would be useful to know how to think things through in such a way as to avoid both selective outrage (where only X seems to matter, but not similar cases Y or Z), and mere ‘what aboutism’, which demands an interest in not only case X but in all the other cases that could be considered – an infinite demand that can never be met. Read more »

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

Nikita Kadan. Hold The Thought, Where The Story Was Interrupted, 2014.

Nikita Kadan. Hold The Thought, Where The Story Was Interrupted, 2014.

Beliefs about the essential goodness or badness of human beings have been at the heart of much political theory.

Beliefs about the essential goodness or badness of human beings have been at the heart of much political theory.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait at Gas Station, April 3, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait at Gas Station, April 3, 2022.