by Mindy Clegg

The election of 2016 represented a new salvo in the American culture wars. Trump’s campaign began with an incendiary speech against immigration from Central and South America, intended to fire up the far-right wing of the GOP. His victory rested in part on a backlash against Secretary Hillary Rodham-Clinton, the center-right Democratic candidate. Trump spent his one term in office stoking the culture wars to new heights, spinning up his base at the expense of any sense of national unity across political lines. Even the still ongoing global pandemic became fodder for the supposedly existential struggle being waged by a “beleaguered” white evangelical Christian minority. Most people point to the Clinton era as the original source of these culture wars. Newt Gingrich and other far-right conservative politicians supported the Ken Starr investigation into President Bill Clinton’s personal history, eventually resulting in a time and money wasting impeachment. This was also the era of the rise of right-wing media, starting with toxic radio host Rush Limbaugh. Although the tone and themes of the modern culture war have some origins here, the concept goes back much further. Here I want to examine some of that history.

It seems obvious, but not everyone agrees on what we mean by culture. For simplicity’s sake, I will refer to a definition of culture as laid down by Clifford Geertz. According to Nasurllah Mambrol, Geertz called culture a “construable sign” and a “context… within which [social events, behaviors, institutions, or processes] can be intelligibly… described.” In the modern world, the nation-state became a primary organizing principle for much of our cultural life. Read more »

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy. June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai.

June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai.

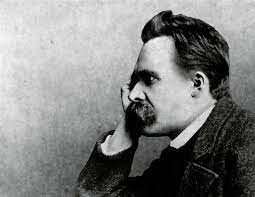

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

Early in the story of

Early in the story of