by Jonathan Kujawa

On “The Joy of Abstraction” by Eugenia Cheng.

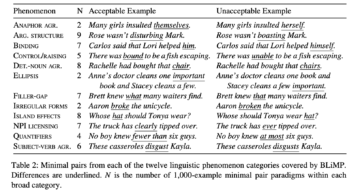

Category theory has variously been called “abstract nonsense,” “diagram chasing,” or the “mathematics of mathematics.” Some mathematicians find it a useful language, some a crucial tool for developing insights and obtaining new results, and more than a few have no use for it at all. I am currently teaching one of our first-year graduate courses. Because of the topic and my tastes, the students have seen a smattering of category theory. Another professor might skip that point of view entirely. This is all to say that even serious students of mathematics are unlikely to see category theory until graduate school.

Eugenia Cheng wrote a Ph.D. thesis entitled “Higher-Dimensional Category Theory: Opetopic Foundations”, has written more than a dozen research papers on all sorts of serious categorical topics, and was formerly a tenured professor at the University of Sheffield, UK. A decade or so ago, Dr. Cheng decided to give up the traditional academic track and put her energy into bringing mathematics to a broad audience. Dr. Cheng is now a Scientist in Residence at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a writer of popular math books, a frequent guest on TV shows, and an all-around evangelizer for thinking about math in novel and humanistic ways.

Eugenia Cheng recently wrote a most peculiar book. It is an introduction to category theory for people whose math education might have stopped with high school. With such modest prerequisites it is remarkable that by the end of the book you are wrestling with advanced topics that my first-year graduate students still haven’t seen! It sounds ambitious and even a little nuts. Dr. Cheng is about the only person in the world with the very particular set of skills needed to write such a book. Read more »

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism).

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism). Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not

In The Art of Revision: The Last Word, Peter Ho Davies notes that writers often have multiple ways to approach the revision of a story. “The main thing,” he writes, “is not to get hung up on the choice; try one and find out. … Sometimes the only way to choose the right option is to choose the wrong one first.” I’m easily hung up on choices of all kinds, and I read those words with a sense of relief.

In The Art of Revision: The Last Word, Peter Ho Davies notes that writers often have multiple ways to approach the revision of a story. “The main thing,” he writes, “is not to get hung up on the choice; try one and find out. … Sometimes the only way to choose the right option is to choose the wrong one first.” I’m easily hung up on choices of all kinds, and I read those words with a sense of relief. A friend just sent me a copy of materials that the Cornwall Alliance is sending to its supporters. Here is an extract [fair use claimed]:

A friend just sent me a copy of materials that the Cornwall Alliance is sending to its supporters. Here is an extract [fair use claimed]: