by Herbert Harris

The greatest privilege of my childhood was growing up in a house where books had their own room.

My father’s library occupied the second floor, the only room without a window air-conditioning unit. On summer afternoons in Washington, DC, when the heat and humidity pressed down like a weight, the rest of the house hummed and rattled with machines straining to keep up. The air in the library stayed stubbornly still. It was the early 1970s, and I was on summer break after tenth grade, retreating there to find the peculiar solitude this room alone offered. Each book I opened sent up a cloud of dust that glittered in the angled sunlight. Shutting the door turned the room into a sauna, but in that quiet stillness, I didn’t mind. It felt like the price of admission to a different world.

The previous summer had unfolded differently. I had just finished ninth grade, where we surveyed the classics of English literature and retraced the decisive moments of Western civilization, reliving the deeds of its great men and women. I spent long afternoons in the library, sinking into those books as the heat pooled around me. I melted into a reclining chair and wandered through the past. That immersion had felt complete, even sufficient. But this summer, I arrived with a different appetite. I was growing skeptical of the Eurocentric narratives threaded through everything I was learning. I sensed there were other stories and vantage points, and I came looking for them.

I picked up the book I had been reading a few days earlier and turned to the page marked with an index card. I searched for the sentence I remembered, but at first the words slipped past me. James Baldwin was writing about a Swiss village, about children shouting “Neger” as he walked through the snow. Seeing the word on the page registered instantly, not as surprise but as recognition. I had learned early what it meant to be called that name in its American form. That knowledge had settled into my body long before I could articulate it. Baldwin was naming something adjacent, something deeper.

“The most illiterate of them is related, in a way that I am not, to Dante, Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Aeschylus, Da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Racine; the cathedral at Chartres says something to them which it cannot say to me… Out of their hymns and dances come Beethoven and Bach. Go back a few centuries and they are in their full glory—but I am in Africa, watching the conquerors arrive.”

It was not the sharp pain of a single insult but a quieter, accumulating recognition. Baldwin described what it meant to stand within a culture that proclaimed itself universal while regarding him as an outsider. He loved the art and literature he named, even as he recognized that history had placed him outside their lineage. “People are trapped in history,” he wrote elsewhere, “and history is trapped in them.” The sentence offered no consolation. It named a condition.

I looked around the room at the volumes of art, literature, philosophy, and history lining the shelves. For the first time, they seemed separated from me by a thin but impenetrable barrier, like an aquarium wall. I could see everything clearly. I could admire it, study it, even love it. But I could not quite enter it as home. I did not yet understand that my father had built this room with precisely that tension in mind, nor that he and my mother had spent their entire teaching careers navigating it.

My father built the library when I was six or seven. I remember him anchoring the floor-to-ceiling shelves into the plaster walls, rubbing stain into the wood with rags, and applying coat after coat of varnish that took forever to dry. One day, when the shelves were finally ready, books emerged from every corner of the house to fill them, as if they had been waiting. Some were meant for me to grow into: children’s books on early civilizations, geography, and dinosaurs. Others would take me years to appreciate. From the beginning, the room made space for me.

My parents were teachers in the DC Public Schools, both graduates of Dunbar, once the flagship of Black secondary education in Washington. Dunbar had been more than a school. It was a community that produced scholars, artists, and political thinkers, sustained by teachers who believed culture could be both rigorous and emancipatory. Students studied Latin and English literature with figures such as Mary Church Terrell and Anna Julia Cooper. They learned history from Carter Woodson and from Haley Douglass, Frederick Douglass’ grandson. By the time I was growing up, that world was already receding.

In the early 1970s, our neighborhood was changing rapidly. The aftershocks of the riots following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination continued to unsettle the city. Neighbors were moving to the suburbs. Houses and storefronts were boarded up. My family had lived there for generations, and my parents could not imagine leaving, yet the forces that had created and sustained Dunbar were gone. As teachers, they felt this every day. Pressure mounted to make curricula immediately relevant, stripping away the long view that had once allowed teachers to turn Latin verbs and historical detail into tools of self-understanding. The dinner table often became the place where these tensions surfaced.

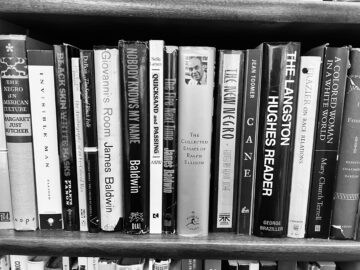

That summer, as I read Baldwin, I began to understand what had animated my parents’ devotion to teaching. Scattered throughout the library were books I had overlooked on my earlier tour of what was often called the canon. They sat quietly between Milton and Shakespeare, alongside coffee-table art volumes and multivolume histories of civilization. I found Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, and James Wright. The library held incompatible histories and ideas side by side. How could the shelves contain such tension?

I spent the rest of that summer with those writers, looking for answers and finding mostly deeper questions. This was the beginning of a long education. The tension Baldwin had named did not resolve itself, but my parents’ example, and the examples of their teachers at Dunbar, showed me that it was possible to live within it without denial.

The essay I read that summer ended with the words, “This world is white no longer, and it will never be white again.” Baldwin understood that the fear such a sentence provokes would not fade. Today, it animates renewed efforts at cultural erasure. It defunds public education and research programs, pressures universities, strips museums, renames streets, cancels holidays, and bans books. The damage is both immediate and cumulative, unfolding on a generational time scale.

Erasure may be policy, but culture survives through use. Libraries endure because someone keeps returning to them, keeps reading, teaching, preserving, passing things on. Like Theseus’ ship, they persist not by remaining unchanged, but by being continually rebuilt, plank by plank, through acts of care.

I have inherited many of my parents’ books, and I have struggled to find room for them on my own crowded shelves. They continue to surprise me. In a copy of James Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It On the Mountain, I found an inscription he had written in 1955 to my father’s sister:

For Norma because she is kind. God bless you.

Jimmy Baldwin

May 13, 1955

Washington.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.