by Michael Liss

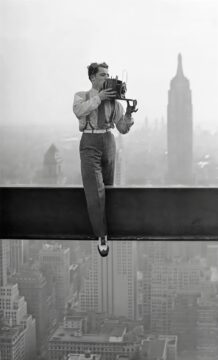

A picture may be worth 1000 words, but this picture, the centerpiece of Christine Roussel’s engaging Lunch on a Beam: The Making of an American Photograph, shows a beam that sits atop 60,000 tons of structural steel, hoisted, positioned, and riveted into place in by as many as 400 ironworkers at a time in 102 working days in 1932.

That’s not an optical illusion you see, unless you think more than 800 feet is just a hop, skip, and jump. It’s a long way down from the top of what popular culture now calls 30 Rock—the building that was first named the RCA Building, then the GE building, and finally (perhaps finally) the somewhat less majestic “Comcast Building.” For simplicity’s sake, let’s call it 30 Rock, not just because that’s what everyone else does, but also because its original values derived from John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s vision for a retail and cultural center in the middle of Manhattan.

Roussel is the Rockefeller Center’s archivist, a job which has afforded her access to voluminous documentary evidence. It has also given her legitimacy as she has hunted down leads to determine just exactly who were those guys so high in the air, and what intrepid photographer (or photographers) scaled the same iron they did to reach the top and get the view. That she consulted so many documents and spoke to so many people—everyone from family members with old photographs thinking they were a match, to members of the Mohawk community, apparently impervious to acrophobia, to union halls, and was still unable to gain certainty is both disappointing and oddly satisfying. These ironworkers were part of a larger brotherhood—men whose grit, strength, agility, and skill built 30 Rock as they built New York. Perhaps they are best seen not as individuals, but as a team, reliant on one another, focused on the same goals, sharing the same risks.

Telling their story is part of her mission, and she does it well. The second part is telling the story of how Rockefeller Center was conceived, how the parcel was assembled, how the design, building, and decor of 30 Rock itself was created and selected, and even how it was staffed. While I have some quibbles about the book’s organization, and, occasionally, Roussel’s choices of emphasis, her retelling of the efforts of men, management, and machines is worth the read.

It was an enormous project that required a great number of things to occur, often in sequence, First the business opportunity—land. Columbia University owned a big parcel of it in midtown that was neither profitable (mostly “improved” by worn-down townhouses and tenements, small shops and even a brothel or two) nor convenient (the University was looking to consolidate its campus uptown in Morningside Heights). The school wanted out from under the burden, but didn’t want to sell outright. It wanted to retain the ground lease, and needed an acquirer who had the capital and the staying power to execute on a plan that could take several years.

The catalyst was the Metropolitan Opera House (actually, the “Old Met”), built on 39th Street and Broadway in the 1880s for New York’s elites (when they weren’t off sojourning in whatever place or places they sojourned in). The Old Met was showing its age.

In Roussel’s telling, there were two prongs to the Met story. One was the physical limitations of the Old Met itself: while it was acoustically excellent and possessed “an elegant, gilded interior,” it had some bad sight lines, a questionable, increasingly industrial location, and a dreary exterior more suited to a warehouse.

All of that might have been tolerable if not for another problem—class. Opera, then as now, has a touch of the patrician to it. This was particularly so in this case, as the Opera Company was the property of the old-money and Gilded Age elites (like the Astors, the Whitneys, the Vanderbilts etc.). Their viewing boxes were held as family estates might be—not to be divided up, abandoned, or sold to outsiders. This irritated some of the more culturally ambitious “new millionaires,” who were tired of being relegated to steerage and wanted to alter the seating calculus. A new building in a new location would solve that.

A consortium (quite pedigreed, but perhaps not enough) that included the immensely wealthy John D. Rockefeller Jr. (Rousel just calls him “Junior”) and names like J.P. Morgan, Otto Kahn, William K. Vanderbilt, and R. Fulton Cutting (a financier, philanthropist, and President of Cooper Union) imagined a retail complex anchored civically by a cultural presence, with the retail space generating the revenues to support it. Junior signed a 24-year lease with Columbia. Then, more quietly, he began to buy adjoining parcels that would augment the Columbia tract to form an almost perfect 12-acre site that could encompass both esthetic and business development. Among Junior’s closest advisors at this stage was his long-time aide Colonel Arthur Woods, who had worked closely with him on the building of Colonial Williamsburg. It was that type of vision—a re-creation and reimagining—that interested Junior.

These were men who were used to getting things done, but life interrupted. On October 24, 1929, Black Thursday took a big bite out of Junior’s partners, and their balance sheets. Within weeks, they backed out entirely.

Junior was faced with a big decision. He could shut the whole thing down without a square foot being done—the parcel would simply revert to what it was, albeit under the ground lease. Or he could reconceive the project, drop the Opera House as uneconomical, develop even more of the parcel for retail, and take on the entire burden. He decided to proceed and retained a strong-minded real estate developer, John R. Todd, to manage the project.

This is the point in the story where Junior’s preference to delegate emerges, and, without the presence of the other original partners, Todd fills the screen. It’s Todd who hires other architects (at reduced rates), Todd who muscles vendors, and Todd (with his men) who handles design, production and management. All this, in Roussel’s words, with “ruthless practicality” and not a small amount of ego.

One thing Todd doesn’t exclusively handle is publicity, and publicity is going to be essential to making the development financially viable, particularly in the middle of the Depression. Todd is charged with building out 5 million square feet on time and on budget. That 5 million square feet must also be filled by obtaining commitments by rent-paying tenants who don’t yet know how their space, or the surrounding development, will eventually look.

Enter Merle Crowell, the former Editor of The American magazine, who is asked to join the project’s in-house publicity shop in the summer of 1931, and starts pumping out…publicity. Crowell issues his first press release July 25, 1931, instantaneously making an opponent of Todd, who starchily reminds him of who’s who in the hierarchy.

It’s a humbling start for Crowell, who not long before had edited a magazine with a circulation approaching 2 million, but he recovers to issue press releases at an accelerating rate. His style is one part mundane, one-part technical information, one part hype, but it clearly works—Rockefeller Center is an ongoing topic of conversation and coverage and rarely does it need to buy advertising space. What Crowell’s alchemy achieves is a sense of movement, a project ever progressing, men hired, equipment and material delivered, steel raised, floors erected—and also excitement—new technology, innovation, attention to esthetics such as décor, and even the hiring of a sculptor and a muralist.

Words matter, but so do visuals, and Crowell wants both. The monumental size and aspirations of the project certainly help, but what also drives attention are the freelance photographers who crawl over the building, looking for that one picture that could convey a sense of wonder. As the RCA building reached its apex, Crowell invites them to show off their own acrobatic skills, climb ladders and head to the top.

That this all goes on in the middle of the Depression, with more than 20 million people unemployed and fortunes and careers broken is something of a miracle, but it’s also a tribute to extraordinary effort for an uncertain result. There are big questions being asked well beyond building a complex—by organized Labor as to whether they will continue to be relevant, by white collar workers with no offices to go to, and by the wealthy, who worry not only about their own finances but about whether the market disruption had called into question the permanence of capitalism itself. Issues of race and class also make their appearance. In a chapter she calls “Not Pictured,” Roussel tells another truth—there are no blacks among the construction workers on the entire project. This wasn’t just Rockefeller management: New York Ironworkers Local 40 admitted none until 1963. Later, after the building is complete and occupied, no blacks are among the elevator operators—management thought the cabs too small, which would bring the passengers too close. It took nearly two decades to rectify that.

As for the men of muscle and skill, they must be hard-headed realists about a job where their lives are in constant danger, and whether an average wage of $1.05 an hour (the equivalent of roughly $21 today) is enough. They know they are being underpaid, but, for almost all of them, it puts food on the table, keeps hope alive for a better future, and, in no way less important, gives them a sense of meaning and purpose.

On September 26, 1932, the men topped out the RCA Building, as a lone ironworker on a single beam with an American flag attached reached for infinity. On October 2, “Lunch on a Beam” was first published in The New York Herald, its smiling subjects launched into an anonymous but eternal fame.

Last week, after reading Roussel’s book, I walked over to Rockefeller Center to take another look. Everything is beautifully kept, and it retains its majesty, like a stand of redwoods, almost outside the measurement of time. There are stories everywhere. I walked past the statuary, past the ice-skating rink, and the (reasonably discrete) Comcast sign, into the entry hall of 30 Rock and looked up at the wall and ceiling murals. A little dark for my tastes, but impressive. Walked outside, blinked in the sun, almost ran headlong into a lighted display, advertising a ride to the Top of the Rock and “The Beam Experience.” Apparently, visitors to the building can now treat themselves to a seat on a rotating beam that’s suspended 12 feet above the 69th-floor Observation Deck, where they can imagine themselves steel workers and enjoy the view.

Tempted, but 840 feet above ground to sit on a narrow beam? I’d need to think about it.

***

Lunch on a Beam: The Making of an American Photograph, by Christine Roussel, scheduled for release April 23, 2026, Brandeis University Press. For further information, contact: [email protected]

*

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.