From Phys.Org:

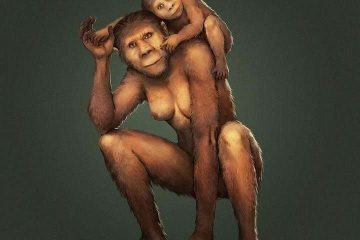

Extended parental care is considered one of the hallmarks of human evolution. A stunning new research result published today in Nature reveals for the first time the parenting habits of one of our earliest extinct ancestors.

Extended parental care is considered one of the hallmarks of human evolution. A stunning new research result published today in Nature reveals for the first time the parenting habits of one of our earliest extinct ancestors.

Analysis of more than two-million-year-old teeth from Australopithecus africanus fossils found in South Africa have revealed that infants were breastfed continuously from birth to about one year of age. Nursing appears to continue in a cyclical pattern in the early years for infants; seasonal changes and food shortages caused the mother to supplement gathered foods with breastmilk. An international research team led by Dr. Renaud Joannes-Boyau of Southern Cross University, and by Dr. Luca Fiorenza and Dr. Justin W. Adams from Monash University, published the details of their research into the species in Nature today.

“For the first time, we gained new insight into the way our ancestors raised their young, and how mothers had to supplement solid food intake with breastmilk when resources were scarce,” said geochemist Dr. Joannes-Boyau from the Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group (GARG) at Southern Cross University.

More here.

We chased the fault line south of Salt Lake City, just past the Cottonwood Canyons, to a small ridge that overlooked a reservoir as silver as the sky. It was October, during a cold drizzle, and the sun was lofted behind the clouds like a shineless mothball. My brother, a Ph.D. student in geology, explained that what appeared to me as indistinct knolls and dips were “expressions” where the fault had deformed the Earth above it. I had spent the day looking at the ground or aiming my eye down my brother’s extended arm to identify subtleties like this. When my gaze finally returned to the Wasatch Mountains, the vision was fresh and horrifying. They were monster-like, tyratnnizing the skyline with their beauty. Under their jagged eminence, my brother and I felt burdened with our knowledge of the region’s fate.

We chased the fault line south of Salt Lake City, just past the Cottonwood Canyons, to a small ridge that overlooked a reservoir as silver as the sky. It was October, during a cold drizzle, and the sun was lofted behind the clouds like a shineless mothball. My brother, a Ph.D. student in geology, explained that what appeared to me as indistinct knolls and dips were “expressions” where the fault had deformed the Earth above it. I had spent the day looking at the ground or aiming my eye down my brother’s extended arm to identify subtleties like this. When my gaze finally returned to the Wasatch Mountains, the vision was fresh and horrifying. They were monster-like, tyratnnizing the skyline with their beauty. Under their jagged eminence, my brother and I felt burdened with our knowledge of the region’s fate. Everyone knows that Turing talked about the imitation game as a way of trying to figure out whether a system is intelligent or not, but what people often don’t appreciate is that in the very same paper, about three paragraphs after the part that everybody quotes, he said, wait a minute, maybe this is the completely wrong track. In fact, what he said was, “Instead of trying to produce a program to simulate the adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child?” Then he gives a bunch of examples of how that could be done.

Everyone knows that Turing talked about the imitation game as a way of trying to figure out whether a system is intelligent or not, but what people often don’t appreciate is that in the very same paper, about three paragraphs after the part that everybody quotes, he said, wait a minute, maybe this is the completely wrong track. In fact, what he said was, “Instead of trying to produce a program to simulate the adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child?” Then he gives a bunch of examples of how that could be done. In 2017, for the second time in recent years, U.S. life expectancy decreased. Headlines blamed the decline on suicides and opioids, and cast impoverished rural whites as the primary victims. A great deal of attention has been focused on Appalachia, whose population is (erroneously) portrayed as uniformly white, poor, and ravaged by drug addiction. White sickness has thus come to stand for what is supposedly wrong with health, health care, and culture in the United States.

In 2017, for the second time in recent years, U.S. life expectancy decreased. Headlines blamed the decline on suicides and opioids, and cast impoverished rural whites as the primary victims. A great deal of attention has been focused on Appalachia, whose population is (erroneously) portrayed as uniformly white, poor, and ravaged by drug addiction. White sickness has thus come to stand for what is supposedly wrong with health, health care, and culture in the United States. Ignorance involves having a false belief, or no belief at all, on a topic. This can be the result of a simple lack of information. In that case, as soon as we read up on the topic we have knowledge. What distinguishes knowledge resistance, by contrast, is that it cannot be fixed by supplying information. It is, as it were, a type of ignorance that is not easily cured.

Ignorance involves having a false belief, or no belief at all, on a topic. This can be the result of a simple lack of information. In that case, as soon as we read up on the topic we have knowledge. What distinguishes knowledge resistance, by contrast, is that it cannot be fixed by supplying information. It is, as it were, a type of ignorance that is not easily cured. The light is dim, the air richly scented. Little purple tea lights flicker in the votive candle rack and the walls are decorated with twining sunflowers, exuberant passionflowers and several canvases of blousy green carnations monogrammed with Oscar Wilde’s prisoner ID number C.3.3. The Temple is a deconsecrated church with an attractive dark wood ceiling and matching antique chairs. A half-size marble statue of Wilde presides. The artists, McDermott and McGough, have painted various icons spelling out pejoratives such as ‘pansy’, ‘faggot’ and ‘cocksucker’, adorned with gold leaf and richly-coloured paint. Towards the back are intricate woodcut-style depictions of massacres with titles like ‘Nun Cutting Rope of Dead Homeric’, black canvases with cut-out fatality statistics, and monochrome portraits of individuals more recently killed by homophobia and transphobia, such as Justin Fashanu, Brandon Teena and Marsha P. Johnson. A placard in the hallway spells out all of the bigotries the temple stands against, ending with the instruction ‘only love here’. Opposite is a purpose-built offertory box ‘For the Sons and Daughters of Oscar Wilde’.

The light is dim, the air richly scented. Little purple tea lights flicker in the votive candle rack and the walls are decorated with twining sunflowers, exuberant passionflowers and several canvases of blousy green carnations monogrammed with Oscar Wilde’s prisoner ID number C.3.3. The Temple is a deconsecrated church with an attractive dark wood ceiling and matching antique chairs. A half-size marble statue of Wilde presides. The artists, McDermott and McGough, have painted various icons spelling out pejoratives such as ‘pansy’, ‘faggot’ and ‘cocksucker’, adorned with gold leaf and richly-coloured paint. Towards the back are intricate woodcut-style depictions of massacres with titles like ‘Nun Cutting Rope of Dead Homeric’, black canvases with cut-out fatality statistics, and monochrome portraits of individuals more recently killed by homophobia and transphobia, such as Justin Fashanu, Brandon Teena and Marsha P. Johnson. A placard in the hallway spells out all of the bigotries the temple stands against, ending with the instruction ‘only love here’. Opposite is a purpose-built offertory box ‘For the Sons and Daughters of Oscar Wilde’. In the spring of 1883 my mother, Maud Du Puy, came from America to spend the summer in Cambridge with her aunt, Mrs Jebb. She was nearly 22, and had never been abroad before; pretty, affectionate, self-willed, and sociable; but not at all a flirt. Indeed her sisters considered her rather stiff with young men. She was very fresh and innocent, something of a Puritan, and with her strong character, was clearly destined for matriarchy.

In the spring of 1883 my mother, Maud Du Puy, came from America to spend the summer in Cambridge with her aunt, Mrs Jebb. She was nearly 22, and had never been abroad before; pretty, affectionate, self-willed, and sociable; but not at all a flirt. Indeed her sisters considered her rather stiff with young men. She was very fresh and innocent, something of a Puritan, and with her strong character, was clearly destined for matriarchy. It is obvious that the discomfort I once felt over taking antidepressants echoed a lingering, deeply ideological societal mistrust. Articles in the consumer press continue to feed that mistrust. The benefit is ‘mostly modest’, a flawed analysis in The New York Times told us in 2018. A widely shared YouTube

It is obvious that the discomfort I once felt over taking antidepressants echoed a lingering, deeply ideological societal mistrust. Articles in the consumer press continue to feed that mistrust. The benefit is ‘mostly modest’, a flawed analysis in The New York Times told us in 2018. A widely shared YouTube  When a movie starts with a diagnosis of terminal cancer, what next? The first thing we saw in Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru” (1952) was an X-ray of a man’s stomach, with a tumor clearly visible, and Lulu Wang’s new film, “The Farewell,” sets off with similar starkness. An aged woman undergoes a CT scan, and we learn that she has Stage IV lung cancer and three months to live. But here’s the difference. Kurosawa’s hero, a meek civil servant, took stock of his mortality and decided to waste not a drop of the time that remained. Wang’s elderly lady, by contrast, is a merry old soul, already skilled at being alive, and requiring no further encouragement. So nobody tells her that she’s going to die.

When a movie starts with a diagnosis of terminal cancer, what next? The first thing we saw in Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru” (1952) was an X-ray of a man’s stomach, with a tumor clearly visible, and Lulu Wang’s new film, “The Farewell,” sets off with similar starkness. An aged woman undergoes a CT scan, and we learn that she has Stage IV lung cancer and three months to live. But here’s the difference. Kurosawa’s hero, a meek civil servant, took stock of his mortality and decided to waste not a drop of the time that remained. Wang’s elderly lady, by contrast, is a merry old soul, already skilled at being alive, and requiring no further encouragement. So nobody tells her that she’s going to die.

Consider the writer as houseguest. Is it a good idea to invite someone into your home whose occupation it is to observe everything? The writer as host might be no better. Even the most thoughtful guest will undoubtedly interfere with the writer’s productivity during the visit. It’s really no surprise that people who write for a living have given us some of our wisest sayings about a visit’s proper length.

Consider the writer as houseguest. Is it a good idea to invite someone into your home whose occupation it is to observe everything? The writer as host might be no better. Even the most thoughtful guest will undoubtedly interfere with the writer’s productivity during the visit. It’s really no surprise that people who write for a living have given us some of our wisest sayings about a visit’s proper length. Adam Tooze in the LRB:

Adam Tooze in the LRB: In Medium, first Seyla Benhabib responds to Raymond Guess piece in Point Magazine

In Medium, first Seyla Benhabib responds to Raymond Guess piece in Point Magazine  “Art museums are in a state of crisis.” The diagnosis is drastic, the remedy equally so: a radical update of both form and function. Hopelessly out of touch with the pulse of contemporary culture and the rhythms of everyday life, the grandiose architecture of the museum must be rethought in terms of adaptability and flexibility, with inert galleries transformed into sites of ongoing experimentation. Likewise the visitor’s experience, still rooted in antiquated models of passive contemplation, must be reimagined as a process of active participation and immersive engagement. Museums must reinvent themselves wholesale, in other words, to “guarantee their survival in a changing world.”

“Art museums are in a state of crisis.” The diagnosis is drastic, the remedy equally so: a radical update of both form and function. Hopelessly out of touch with the pulse of contemporary culture and the rhythms of everyday life, the grandiose architecture of the museum must be rethought in terms of adaptability and flexibility, with inert galleries transformed into sites of ongoing experimentation. Likewise the visitor’s experience, still rooted in antiquated models of passive contemplation, must be reimagined as a process of active participation and immersive engagement. Museums must reinvent themselves wholesale, in other words, to “guarantee their survival in a changing world.”