Jessica F. Kane in The New York Times:

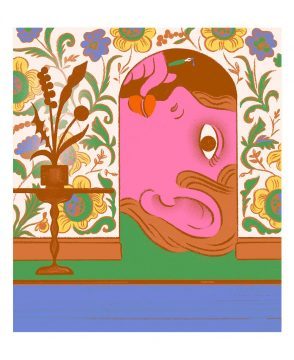

Consider the writer as houseguest. Is it a good idea to invite someone into your home whose occupation it is to observe everything? The writer as host might be no better. Even the most thoughtful guest will undoubtedly interfere with the writer’s productivity during the visit. It’s really no surprise that people who write for a living have given us some of our wisest sayings about a visit’s proper length.

Consider the writer as houseguest. Is it a good idea to invite someone into your home whose occupation it is to observe everything? The writer as host might be no better. Even the most thoughtful guest will undoubtedly interfere with the writer’s productivity during the visit. It’s really no surprise that people who write for a living have given us some of our wisest sayings about a visit’s proper length.

It was a delightful visit — perfect in being much too short (Jane Austen)

Fish and visitors stink in three days (Benjamin Franklin)

Superior people never make long visits (Marianne Moore)

If you doubt their seriousness, take note: When Hans Christian Andersen stayed with Charles Dickens three weeks longer than originally planned, their friendship never recovered. Still, lengthy visits have played an important role in a number of literary lives — writers who, intentionally or not, leveraged being a houseguest into an asset.

Samuel Johnson’s house in London was full of people reliant on him in one way or another. When he needed respite, he traveled to Streatham Park, outside London, to be the houseguest of the Thrales. He was such a frequent visitor that he had his own room and was treated as a member of the family, his likes and dislikes known, his various ailments — melancholia, insomnia — understood. These trips to the countryside offered a psychological solace he could achieve only in the care of Streatham’s mistress, the devoted Hester Thrale. She kept the house quiet for him and provided interesting dinner guests for conversation in the evening. He worked if he could, or waited out the depressions that often overwhelmed him. For a distressed author it was the ideal arrangement — not unlike any number of residencies for which writers compete today.

More here.