Rachel Cooke in The Guardian:

It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab, Pakistan, to the village of Shah Sadar Din, and the first time the journalist Sanam Maher made the journey, her eyes widened at every turn. In Dera Ghazi Khan, a town close to the village, none of the faces of the women she saw on the streets were visible. Some wore what looked like black ski masks with slits for their eyes. Others were covered by burqas with no eye-slits at all and so extensive that she felt half naked under her own dupatta (scarf). A thin funnel rises from the top of this kind of burqa: a device to allow air inside so that the wearer does not suffocate. Her contact in the town, noticing her staring, mentioned a place not far away, where the tribal belt of Balochistan province starts: the women there, he told her, were not given shoes. She was confused. Why not? “You’ll never look at any man if you’re scared of where your naked foot might fall when you leave your home,” he replied impatiently, as if it was the most obvious thing in the world.

It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab, Pakistan, to the village of Shah Sadar Din, and the first time the journalist Sanam Maher made the journey, her eyes widened at every turn. In Dera Ghazi Khan, a town close to the village, none of the faces of the women she saw on the streets were visible. Some wore what looked like black ski masks with slits for their eyes. Others were covered by burqas with no eye-slits at all and so extensive that she felt half naked under her own dupatta (scarf). A thin funnel rises from the top of this kind of burqa: a device to allow air inside so that the wearer does not suffocate. Her contact in the town, noticing her staring, mentioned a place not far away, where the tribal belt of Balochistan province starts: the women there, he told her, were not given shoes. She was confused. Why not? “You’ll never look at any man if you’re scared of where your naked foot might fall when you leave your home,” he replied impatiently, as if it was the most obvious thing in the world.

Maher, who is based in Karachi, was in Shah Sadar Din to investigate the life and death of Fouzia Azeem, AKA Qandeel Baloch, Pakistan’s first social media celebrity and the woman some like to describe as its Kim Kardashian. Baloch was born here, the daughter of a poor family, and when she was murdered on 15 July, 2016, her body was supposed to end up in the village’s brown river, a spot well known for being the final resting place of women who have died at the hands of their relatives in so-called “honour” killings. On the day in question, however, there were too many people around to manage this (another villager had died; crowds of mourners were gathering). Baloch’s mother found the body at home; her father informed the authorities. When the police arrived, Baloch was still lying where she had been drugged and asphyxiated, in a bedroom at the small house that she rented for her parents in Multan. She was just 26.

“Visiting Shah Sadar Din was a huge culture shock for me,” says Maher, whose book about the case, A Woman Like Her, is published in the UK next month (it has already caused something of a sensation in south Asia). “The women were so completely covered: I’d never seen that anywhere that I’d lived or worked. But it’s important to say straight off that, though this is typical of south Punjab, it has nothing at all to do with religion. These [dress codes] are cultural diktats, just as honour killing and other forms of violence against women are cultural diktats. This is men wanting to control how the women around them live.”

More here.

When did nature become a good for cities? When did city dwellers start imagining nature to be something they were missing? Today, urbanites’ moral associations with nature are so obvious and widely shared that a recent New Yorker cartoon of a couple at the dinner table was captioned: “Is this from the community garden? It tastes sanctimonious.” For better or worse, most of us are so steeped in this view of nature that it is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise. But it once was.

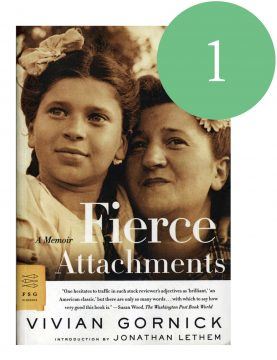

When did nature become a good for cities? When did city dwellers start imagining nature to be something they were missing? Today, urbanites’ moral associations with nature are so obvious and widely shared that a recent New Yorker cartoon of a couple at the dinner table was captioned: “Is this from the community garden? It tastes sanctimonious.” For better or worse, most of us are so steeped in this view of nature that it is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise. But it once was. “I remember only the women,” Vivian Gornick writes near the start of her memoir of growing up in the Bronx tenements in the 1940s, surrounded by the blunt, brawling, yearning women of the neighborhood, chief among them her indomitable mother. “I absorbed them as I would chloroform on a cloth laid against my face. It has taken me 30 years to understand how much of them I understood.”

“I remember only the women,” Vivian Gornick writes near the start of her memoir of growing up in the Bronx tenements in the 1940s, surrounded by the blunt, brawling, yearning women of the neighborhood, chief among them her indomitable mother. “I absorbed them as I would chloroform on a cloth laid against my face. It has taken me 30 years to understand how much of them I understood.” With the ability to use tools, solve complex puzzles, and even

With the ability to use tools, solve complex puzzles, and even  The photos of

The photos of  March 2019: a woman is standing in front of some Swatch watches on a daytime TV antiques show. The presenter asks which is her favourite. “Probably this one,” she answers, pointing to a watch adorned with a cartoon barking mutt. “I just like the dog – it makes me smile.” The story of how Keith Haring’s symbols became so ubiquitous that they ended up on the wrists of Middle England as much as on the bedroom walls of 1980s Aids activists is both the contradiction and the genius of the New York street artist, whose star burned fast and acid bright. Tate Liverpool’s superb retrospective traces Haring’s ten-year flight from street artist to global consumer brand, from scrawling on the subway to painting the Berlin Wall, and details the turbulent political backdrop behind his work. We know many of his motifs well – the dog, the crawling baby, the three-eyed face – his thick black lines and dancing figures, but there’s nothing superficial about these deceptively simple scrawls.

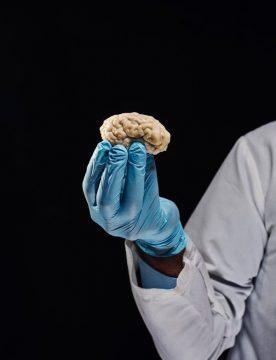

March 2019: a woman is standing in front of some Swatch watches on a daytime TV antiques show. The presenter asks which is her favourite. “Probably this one,” she answers, pointing to a watch adorned with a cartoon barking mutt. “I just like the dog – it makes me smile.” The story of how Keith Haring’s symbols became so ubiquitous that they ended up on the wrists of Middle England as much as on the bedroom walls of 1980s Aids activists is both the contradiction and the genius of the New York street artist, whose star burned fast and acid bright. Tate Liverpool’s superb retrospective traces Haring’s ten-year flight from street artist to global consumer brand, from scrawling on the subway to painting the Berlin Wall, and details the turbulent political backdrop behind his work. We know many of his motifs well – the dog, the crawling baby, the three-eyed face – his thick black lines and dancing figures, but there’s nothing superficial about these deceptively simple scrawls. A few years ago, a scientist named Nenad Sestan began throwing around an idea for an experiment so obviously insane, so “wild” and “totally out there,” as he put it to me recently, that at first he told almost no one about it: not his wife or kids, not his bosses in Yale’s neuroscience department, not the dean of the university’s medical school. Like everything Sestan studies, the idea centered on the mammalian brain. More specific, it centered on the tree-shaped neurons that govern speech, motor function and thought — the cells, in short, that make us who we are. In the course of his research, Sestan, an expert in developmental neurobiology, regularly ordered slices of animal and human brain tissue from various brain banks, which shipped the specimens to Yale in coolers full of ice. Sometimes the tissue arrived within three or four hours of the donor’s death. Sometimes it took more than a day. Still, Sestan and his team were able to culture, or grow, active cells from that tissue — tissue that was, for all practical purposes, entirely dead. In the right circumstances, they could actually keep the cells alive for several weeks at a stretch.

A few years ago, a scientist named Nenad Sestan began throwing around an idea for an experiment so obviously insane, so “wild” and “totally out there,” as he put it to me recently, that at first he told almost no one about it: not his wife or kids, not his bosses in Yale’s neuroscience department, not the dean of the university’s medical school. Like everything Sestan studies, the idea centered on the mammalian brain. More specific, it centered on the tree-shaped neurons that govern speech, motor function and thought — the cells, in short, that make us who we are. In the course of his research, Sestan, an expert in developmental neurobiology, regularly ordered slices of animal and human brain tissue from various brain banks, which shipped the specimens to Yale in coolers full of ice. Sometimes the tissue arrived within three or four hours of the donor’s death. Sometimes it took more than a day. Still, Sestan and his team were able to culture, or grow, active cells from that tissue — tissue that was, for all practical purposes, entirely dead. In the right circumstances, they could actually keep the cells alive for several weeks at a stretch. Leonard Benardo in The American Progress:

Leonard Benardo in The American Progress: Eric Foner in The Nation:

Eric Foner in The Nation: Lida Maxwell in the LA Review of Books:

Lida Maxwell in the LA Review of Books: Martin Jay in The Point:

Martin Jay in The Point: Unsurprisingly from the author of The Strangest Man, an award-winning biography of Dirac, Farmelo has offered a thoughtful, well-informed reply to those who believe the quest for mathematical beauty has led theoretical physicists into adopting sterile, ultra-mathematical approaches divorced from reality. He makes a persuasive case as he argues that theorists have not spent the last 40 years wasting their time writing quasi-scientific fairytales and that many of the ideas and concepts that have emerged will endure.

Unsurprisingly from the author of The Strangest Man, an award-winning biography of Dirac, Farmelo has offered a thoughtful, well-informed reply to those who believe the quest for mathematical beauty has led theoretical physicists into adopting sterile, ultra-mathematical approaches divorced from reality. He makes a persuasive case as he argues that theorists have not spent the last 40 years wasting their time writing quasi-scientific fairytales and that many of the ideas and concepts that have emerged will endure. Walter Bagehot — pronounced Badge-it — was first called “the greatest Victorian” by that capaciously learned historian of 19th-century England, G.M. Young. The phrase has been attached to Bagehot’s name ever since and is again used by James Grant in the subtitle of this new biography, even though it would be more accurate to call its subject “the most versatile Victorian.”

Walter Bagehot — pronounced Badge-it — was first called “the greatest Victorian” by that capaciously learned historian of 19th-century England, G.M. Young. The phrase has been attached to Bagehot’s name ever since and is again used by James Grant in the subtitle of this new biography, even though it would be more accurate to call its subject “the most versatile Victorian.” B

B It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab,

It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab,