Alyssa Battistoni in n+1:

Alyssa Battistoni in n+1:

IN 2007, WHEN I WAS 21 YEARS OLD, I wrote an indignant letter to the New York Times in response to a column by Thomas Friedman. Friedman had called out my generation as a quiescent one: “too quiet, too online, for its own good.” “Our generation is lacking not courage or will,” I insisted, “but the training and experience to do the hard work of organizing — whether online or in person — that will lead to political power.”

I myself had never really organized. I had recently interned for a community-organizing nonprofit in Washington DC, a few months before Barack Obama became the world’s most famous (former) community organizer, but what I learned was the language of organizing — how to write letters to the editor about its necessity — not how to actually do it. I graduated from college, and some months later, the global economy collapsed. I spent the next years occasionally showing up to protests. I went to Zuccotti Park and to an attempted general strike in Oakland; I participated in demonstrations against rising student fees in London and against police killings in New York. I wrote more exhortatory articles. But it wasn’t until I went to graduate school at Yale, where a campaign for union recognition had been going on for nearly three decades, that I learned to do the thing I’d by then been advocating for years.

More here.

Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson in New York Review of Books:

Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson in New York Review of Books: John Case in The New Republic:

John Case in The New Republic: T

T I was first alerted to Raymond Geuss’s sour anti-commemoration of Jürgen Habermas’s ninetieth birthday, “

I was first alerted to Raymond Geuss’s sour anti-commemoration of Jürgen Habermas’s ninetieth birthday, “

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon.

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon. In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries?

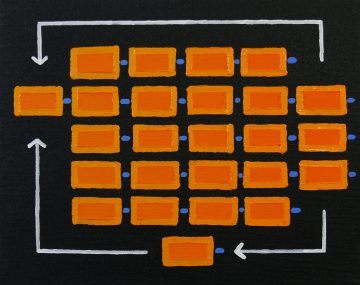

In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries? Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.

Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.

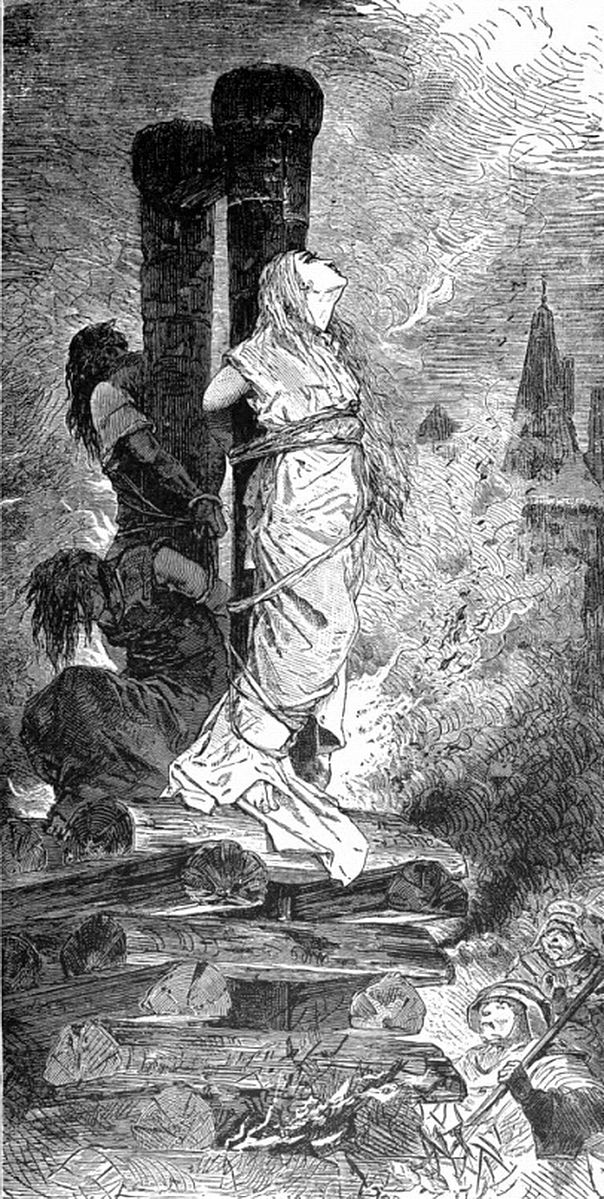

The theory of Darwinian cultural evolution is gaining currency in many parts of the socio-cultural sciences, but it remains contentious. Critics claim that the theory is either fundamentally mistaken or boils down to a fancy re-description of things we knew all along. We will argue that cultural Darwinism can indeed resolve long-standing socio-cultural puzzles; this is demonstrated through a cultural Darwinian analysis of the European witch persecutions. Two central and unresolved questions concerning witch-hunts will be addressed. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, a remarkable and highly specific concept of witchcraft was taking shape in Europe. The first question is: who constructed it? With hindsight, we can see that the concept contains many elements that appear to be intelligently designed to ensure the continuation of witch persecutions, such as the witches’ sabbat, the diabolical pact, nightly flight, and torture as a means of interrogation. The second question is: why did beliefs in witchcraft and witch-hunts persist and disseminate, despite the fact that, as many historians have concluded, no one appears to have substantially benefited from them? Historians have convincingly argued that witch-hunts were not inspired by some hidden agenda; persecutors genuinely believed in the threat of witchcraft to their communities. We propose that the apparent ‘design’ exhibited by concepts of witchcraft resulted from a Darwinian process of evolution, in which cultural variants that accidentally enhanced the reproduction of the witch-hunts were selected and accumulated. We argue that witch persecutions form a prime example of a ‘viral’ socio-cultural phenomenon that reproduces ‘selfishly’, even harming the interests of its human hosts.

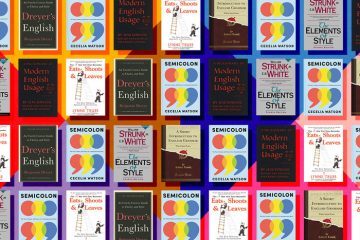

The theory of Darwinian cultural evolution is gaining currency in many parts of the socio-cultural sciences, but it remains contentious. Critics claim that the theory is either fundamentally mistaken or boils down to a fancy re-description of things we knew all along. We will argue that cultural Darwinism can indeed resolve long-standing socio-cultural puzzles; this is demonstrated through a cultural Darwinian analysis of the European witch persecutions. Two central and unresolved questions concerning witch-hunts will be addressed. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, a remarkable and highly specific concept of witchcraft was taking shape in Europe. The first question is: who constructed it? With hindsight, we can see that the concept contains many elements that appear to be intelligently designed to ensure the continuation of witch persecutions, such as the witches’ sabbat, the diabolical pact, nightly flight, and torture as a means of interrogation. The second question is: why did beliefs in witchcraft and witch-hunts persist and disseminate, despite the fact that, as many historians have concluded, no one appears to have substantially benefited from them? Historians have convincingly argued that witch-hunts were not inspired by some hidden agenda; persecutors genuinely believed in the threat of witchcraft to their communities. We propose that the apparent ‘design’ exhibited by concepts of witchcraft resulted from a Darwinian process of evolution, in which cultural variants that accidentally enhanced the reproduction of the witch-hunts were selected and accumulated. We argue that witch persecutions form a prime example of a ‘viral’ socio-cultural phenomenon that reproduces ‘selfishly’, even harming the interests of its human hosts. The reason we pay happily for these manuals is straightforward, if a little sad. We’ve been convinced that we need them — that without them, we’d be lost. Readers aren’t drawn to in-depth arguments on punctuation and conjugation for the sheer fun of it; they’re sold on the promise of progress, of betterment. These books benefit from the dire misconception that they are for everyday people, when, in fact, they’re for editors and educators.

The reason we pay happily for these manuals is straightforward, if a little sad. We’ve been convinced that we need them — that without them, we’d be lost. Readers aren’t drawn to in-depth arguments on punctuation and conjugation for the sheer fun of it; they’re sold on the promise of progress, of betterment. These books benefit from the dire misconception that they are for everyday people, when, in fact, they’re for editors and educators. Contemporary technological anxiety—when not directed towards the internet wholesale—is just as often pitched against sound. We’ve recently started to ask what platform monopolies are doing to the quality of music, or whether Amazon is killing record (and book) stores, or if podcasts are further ensnaring us online, destroying our private thoughts. It’s enough, given his pedagogical wisdom, to make us wonder: What would Berger say?—about earbuds or

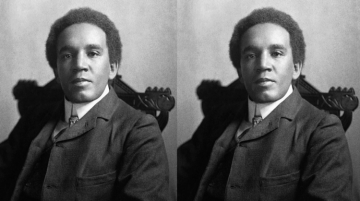

Contemporary technological anxiety—when not directed towards the internet wholesale—is just as often pitched against sound. We’ve recently started to ask what platform monopolies are doing to the quality of music, or whether Amazon is killing record (and book) stores, or if podcasts are further ensnaring us online, destroying our private thoughts. It’s enough, given his pedagogical wisdom, to make us wonder: What would Berger say?—about earbuds or  Coleridge-Taylor was deeply interested in both African and African-American melodies. A meeting with the American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1896, for example, had let to a vocal work, African Romances, with the two of them deciding to put on a series of performances together. Another work, the Twenty-Four Negro Melodies for piano, was influenced by Dunbar’s work. “What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music,” Coleridge-Taylor wrote in the preface to the score, “Dvořák for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro melodies.” But though the composer’s political consciousness had been informed by an abiding interest in pan-Africanism, though his explorations of his paternal ancestry had him briefly flirting with the idea of relocating to the United States, he primarily filtered the raw materials of black American and African music through a distinctly European sensibility, Brahms and Dvořák being his guiding lights. Coleridge-Taylor’s true métier was the realm of light English music, and as interest in that field diminished with the passing of the 20th century, with the decline of the amateur choruses that once would have taken up such repertoire, so too did an interest in his music. This was already true by 1912, the year the composer died from pneumonia, having collapsed at the West Croydon station, while waiting for a train.

Coleridge-Taylor was deeply interested in both African and African-American melodies. A meeting with the American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1896, for example, had let to a vocal work, African Romances, with the two of them deciding to put on a series of performances together. Another work, the Twenty-Four Negro Melodies for piano, was influenced by Dunbar’s work. “What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music,” Coleridge-Taylor wrote in the preface to the score, “Dvořák for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro melodies.” But though the composer’s political consciousness had been informed by an abiding interest in pan-Africanism, though his explorations of his paternal ancestry had him briefly flirting with the idea of relocating to the United States, he primarily filtered the raw materials of black American and African music through a distinctly European sensibility, Brahms and Dvořák being his guiding lights. Coleridge-Taylor’s true métier was the realm of light English music, and as interest in that field diminished with the passing of the 20th century, with the decline of the amateur choruses that once would have taken up such repertoire, so too did an interest in his music. This was already true by 1912, the year the composer died from pneumonia, having collapsed at the West Croydon station, while waiting for a train. Will the robots of the future be able to replicate human thought? Most engineers assume so with a casual fatalism: the rate of advance in artificial intelligence (AI) is so rapid that it is only a matter of time before robots indistinguishable from human beings are built. Will the robots of the future surpass and then subordinate their creators? Some of the initiated believe so. This impending apocalypse has a name – “the singularity” – and is confidently expected in some quarters as soon as 2045.

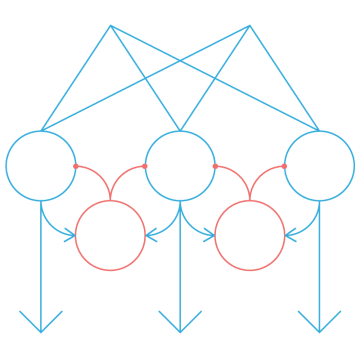

Will the robots of the future be able to replicate human thought? Most engineers assume so with a casual fatalism: the rate of advance in artificial intelligence (AI) is so rapid that it is only a matter of time before robots indistinguishable from human beings are built. Will the robots of the future surpass and then subordinate their creators? Some of the initiated believe so. This impending apocalypse has a name – “the singularity” – and is confidently expected in some quarters as soon as 2045. At each instant, our senses gather oodles of sensory information, yet somehow our brains reduce that fire hose of input to simple realities: A car is honking. A bluebird is flying.

At each instant, our senses gather oodles of sensory information, yet somehow our brains reduce that fire hose of input to simple realities: A car is honking. A bluebird is flying. RECENTLY

RECENTLY Survivor camps established after shipwrecks provide fascinating data about the societies that groups of people make when it’s left up to them, about how and why social order might vary, and about what arrangements are the most conducive to peace and survival. An archipelago of shipwrecks, formed over centuries, more or less at random, has resulted in people participating, unintentionally, in multiple trials of this experiment.

Survivor camps established after shipwrecks provide fascinating data about the societies that groups of people make when it’s left up to them, about how and why social order might vary, and about what arrangements are the most conducive to peace and survival. An archipelago of shipwrecks, formed over centuries, more or less at random, has resulted in people participating, unintentionally, in multiple trials of this experiment.