Bailey Trela at the LARB:

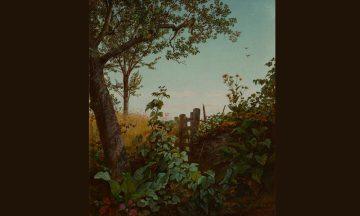

The painting that kicked it all off, Ruskin’s own Fragment of the Alps, goes a long way towards explaining the intermingling of spirituality and scientific exactitude found in the best of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ works. Shuttled around America in a touring exhibition in the year 1857, the small canvas is a fantasia of vivid yellows and saturated purples, yet this almost surreal medley stems from no more mystical source than Ruskin’s hidebound attention to the play of light on stone. As the exhibition notes make clear, the careful delineation of the natural environment was a profoundly moral act for Ruskin. Detail became a form of prayer, a sort of thanksgiving for and hymn to God’s creation. The delicate plexing of boughs in Charles Herbert Moore’s Pine Tree, from 1868, are a perfect non-Ruskinian example of this drive — the detail is so fine that the tree seems to be melting upward, the fine pen markings gradually being blown away by the wind.

The painting that kicked it all off, Ruskin’s own Fragment of the Alps, goes a long way towards explaining the intermingling of spirituality and scientific exactitude found in the best of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ works. Shuttled around America in a touring exhibition in the year 1857, the small canvas is a fantasia of vivid yellows and saturated purples, yet this almost surreal medley stems from no more mystical source than Ruskin’s hidebound attention to the play of light on stone. As the exhibition notes make clear, the careful delineation of the natural environment was a profoundly moral act for Ruskin. Detail became a form of prayer, a sort of thanksgiving for and hymn to God’s creation. The delicate plexing of boughs in Charles Herbert Moore’s Pine Tree, from 1868, are a perfect non-Ruskinian example of this drive — the detail is so fine that the tree seems to be melting upward, the fine pen markings gradually being blown away by the wind.

more here.

Tate’s final work will lodge him permanently in the landscape of American poetry, but, like Dickinson, he will always also be a local phenomenon. In 2004, he published a poem, “Of Whom Am I Afraid?,” about encountering “an old grizzled farmer” at the supply store. They strike up a conversation about Dickinson’s poetry. (It may seem unlikely, or “Surreal,” but Amherst has always had its share of literary farmers.) These two men discuss Dickinson’s toughness; then the farmer, testing Tate’s own mettle, slaps him across the face. Somehow this is a form of homage, and Tate commemorates the occasion by buying “some ice tongs . . . for which I had no earthly use.” They wind up, instead, in a poem. It’s that higher utility that Tate always sought.

Tate’s final work will lodge him permanently in the landscape of American poetry, but, like Dickinson, he will always also be a local phenomenon. In 2004, he published a poem, “Of Whom Am I Afraid?,” about encountering “an old grizzled farmer” at the supply store. They strike up a conversation about Dickinson’s poetry. (It may seem unlikely, or “Surreal,” but Amherst has always had its share of literary farmers.) These two men discuss Dickinson’s toughness; then the farmer, testing Tate’s own mettle, slaps him across the face. Somehow this is a form of homage, and Tate commemorates the occasion by buying “some ice tongs . . . for which I had no earthly use.” They wind up, instead, in a poem. It’s that higher utility that Tate always sought. There never seems to be enough time to accomplish all the things we must do. Life gets busier and busier. But what does all that busy-ness add to our lives? Mainstream culture tells us that being busy is a virtue, so we want to be busy even if we complain about it. It means we’re productive and have purpose. Ideas like “time is money” and “idle hands are the devil’s workshop” have helped to define our culture. Both ideas work in concert with the global capitalist economy, which depends on keeping us busy in order to increase productivity, expand markets, and encourage hyper-consumption. Busy-ness also helps to keep us from questioning the assumptions and values that drive busy-ness itself. Busy-ness is part of a broader set of structures that limit our choices and our ability to feel satisfied. What we call the “

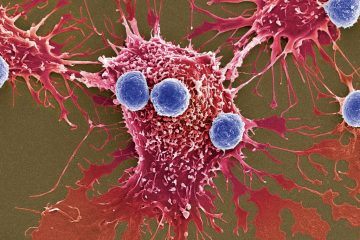

There never seems to be enough time to accomplish all the things we must do. Life gets busier and busier. But what does all that busy-ness add to our lives? Mainstream culture tells us that being busy is a virtue, so we want to be busy even if we complain about it. It means we’re productive and have purpose. Ideas like “time is money” and “idle hands are the devil’s workshop” have helped to define our culture. Both ideas work in concert with the global capitalist economy, which depends on keeping us busy in order to increase productivity, expand markets, and encourage hyper-consumption. Busy-ness also helps to keep us from questioning the assumptions and values that drive busy-ness itself. Busy-ness is part of a broader set of structures that limit our choices and our ability to feel satisfied. What we call the “ Austin Burt and Andrea Crisanti had been trying for eight years to hijack the mosquito genome. They wanted to bypass natural selection and plug in a gene that would mushroom through the population faster than a mutation handed down by the usual process of inheritance. In the back of their minds was a way to prevent malaria by spreading a gene to knock out mosquito populations so that they cannot transmit the disease. Crisanti remembers failing over and over. But finally, in 2011, the two geneticists at Imperial College London got back the DNA results they’d been hoping for: a gene they had inserted into the mosquito genome had radiated through the population, reaching more than 85% of the insects’ descendants

Austin Burt and Andrea Crisanti had been trying for eight years to hijack the mosquito genome. They wanted to bypass natural selection and plug in a gene that would mushroom through the population faster than a mutation handed down by the usual process of inheritance. In the back of their minds was a way to prevent malaria by spreading a gene to knock out mosquito populations so that they cannot transmit the disease. Crisanti remembers failing over and over. But finally, in 2011, the two geneticists at Imperial College London got back the DNA results they’d been hoping for: a gene they had inserted into the mosquito genome had radiated through the population, reaching more than 85% of the insects’ descendants That raises a whole range of very familiar and long-standing issues that have afflicted the Left, leading to debates in India (and no doubt in other places as well) between the organised Left and what has come to be called the “ultra-Left” and the insurgent Left.

That raises a whole range of very familiar and long-standing issues that have afflicted the Left, leading to debates in India (and no doubt in other places as well) between the organised Left and what has come to be called the “ultra-Left” and the insurgent Left. It doesn’t mean much to say music affects your brain — everything that happens to you affects your brain. But music affects your brain in certain specific ways, from changing our mood to helping us learn. As both a neuroscientist and an opera singer, Indre Viskontas is the ideal person to talk about the relationship between music and the brain. Her new book, How Music Can Make You Better, digs into why we love music, how it can unite and divide us, and how music has a special impact on the very young and the very old.

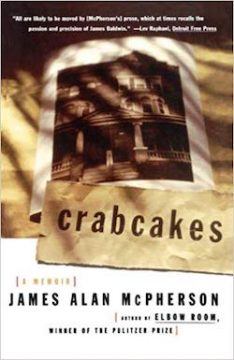

It doesn’t mean much to say music affects your brain — everything that happens to you affects your brain. But music affects your brain in certain specific ways, from changing our mood to helping us learn. As both a neuroscientist and an opera singer, Indre Viskontas is the ideal person to talk about the relationship between music and the brain. Her new book, How Music Can Make You Better, digs into why we love music, how it can unite and divide us, and how music has a special impact on the very young and the very old. JAMES ALAN MCPHERSON’S memoir Crabcakes begins with the death of his tenant, Mrs. Channie Washington. A traditional memoir might have sketched McPherson’s upbringing: the strapped childhood in segregated Savannah, Georgia, as the son of an electrician and a maid, and his ascent to Harvard Law School in the late ’60s. He might have noted that during that time, his short story “Gold Coast” won a competition sponsored by The Atlantic, and that two years later, with the story collection Hue and Cry already under his belt, he received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He could have also mentioned that his second collection Elbow Room, published in 1977, earned him a Pulitzer Prize: the first African American to win one for fiction.

JAMES ALAN MCPHERSON’S memoir Crabcakes begins with the death of his tenant, Mrs. Channie Washington. A traditional memoir might have sketched McPherson’s upbringing: the strapped childhood in segregated Savannah, Georgia, as the son of an electrician and a maid, and his ascent to Harvard Law School in the late ’60s. He might have noted that during that time, his short story “Gold Coast” won a competition sponsored by The Atlantic, and that two years later, with the story collection Hue and Cry already under his belt, he received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He could have also mentioned that his second collection Elbow Room, published in 1977, earned him a Pulitzer Prize: the first African American to win one for fiction. In short, Western narratives about China throughout the 1990s hinged on the logic that capitalist development must end with liberal democracy. In hindsight, however, precisely the opposite seems to have occurred in the People’s Republic. Rather than being a political albatross on the Party’s neck, the legacy of Tiananmen, the chaotic aftermath of Soviet collapse, and the difficulties in bridging east-west divisions in Europe, has paradoxically bolstered the Party’s legitimacy in China. Indeed, public opinion surveys in recent years have consistently found that a majority of Chinese citizens are not only content with the Party’s leadership but broadly more optimistic about their personal future and that of their country relative to those polled in the West. The same surveys also found that Chinese people tend to be unsympathetic to proposals for major shifts in China’s c

In short, Western narratives about China throughout the 1990s hinged on the logic that capitalist development must end with liberal democracy. In hindsight, however, precisely the opposite seems to have occurred in the People’s Republic. Rather than being a political albatross on the Party’s neck, the legacy of Tiananmen, the chaotic aftermath of Soviet collapse, and the difficulties in bridging east-west divisions in Europe, has paradoxically bolstered the Party’s legitimacy in China. Indeed, public opinion surveys in recent years have consistently found that a majority of Chinese citizens are not only content with the Party’s leadership but broadly more optimistic about their personal future and that of their country relative to those polled in the West. The same surveys also found that Chinese people tend to be unsympathetic to proposals for major shifts in China’s c

Great reporting isn’t usually harmed by the reporter having a poor character. It may even be improved by it. Lillian just happened to be hard-bitten in the right way. Her pieces relied on a ruthlessness, sometimes a viciousness, that she didn’t try to hide and that other people liked to comment on. She talked a lot about not being egotistical and so on, but reporters who talk a great deal about not obtruding on the reporting are usually quite aware, at some level, that objectivity is probably a fiction, and that they are most present when imagining they’re invisible. (Lillian was in at least two minds about this, possibly six. One minute she’d say a reporter had to let the story be the story, the next she’d say it was ridiculous: a reporter is ‘chemically’ involved in the story she is writing.) By the time I knew her, Lillian was struggling against a sense that she had caused pain to Shawn’s widow, Cecille, who was still alive, and permanently changed the public view of that most quiet and dedicated of New Yorker editors. Though I liked the book, I believed she was fooling herself if she thought there wasn’t something more than candour at work in her portrayal of Shawn’s family and the reality of his life with them. She claimed she was his ‘real’ wife and that her adopted son, Erik, was ‘theirs’. She knew this was tendentious and took out her anxiety on people who pointed it out.

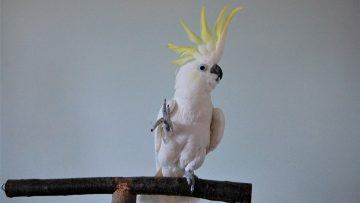

Great reporting isn’t usually harmed by the reporter having a poor character. It may even be improved by it. Lillian just happened to be hard-bitten in the right way. Her pieces relied on a ruthlessness, sometimes a viciousness, that she didn’t try to hide and that other people liked to comment on. She talked a lot about not being egotistical and so on, but reporters who talk a great deal about not obtruding on the reporting are usually quite aware, at some level, that objectivity is probably a fiction, and that they are most present when imagining they’re invisible. (Lillian was in at least two minds about this, possibly six. One minute she’d say a reporter had to let the story be the story, the next she’d say it was ridiculous: a reporter is ‘chemically’ involved in the story she is writing.) By the time I knew her, Lillian was struggling against a sense that she had caused pain to Shawn’s widow, Cecille, who was still alive, and permanently changed the public view of that most quiet and dedicated of New Yorker editors. Though I liked the book, I believed she was fooling herself if she thought there wasn’t something more than candour at work in her portrayal of Shawn’s family and the reality of his life with them. She claimed she was his ‘real’ wife and that her adopted son, Erik, was ‘theirs’. She knew this was tendentious and took out her anxiety on people who pointed it out. Before he became an internet sensation, before he made scientists reconsider the nature of dancing, before the

Before he became an internet sensation, before he made scientists reconsider the nature of dancing, before the  Scientists

Scientists  When did nature become a good for cities? When did city dwellers start imagining nature to be something they were missing? Today, urbanites’ moral associations with nature are so obvious and widely shared that a recent New Yorker cartoon of a couple at the dinner table was captioned: “Is this from the community garden? It tastes sanctimonious.” For better or worse, most of us are so steeped in this view of nature that it is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise. But it once was.

When did nature become a good for cities? When did city dwellers start imagining nature to be something they were missing? Today, urbanites’ moral associations with nature are so obvious and widely shared that a recent New Yorker cartoon of a couple at the dinner table was captioned: “Is this from the community garden? It tastes sanctimonious.” For better or worse, most of us are so steeped in this view of nature that it is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise. But it once was. “I remember only the women,” Vivian Gornick writes near the start of her memoir of growing up in the Bronx tenements in the 1940s, surrounded by the blunt, brawling, yearning women of the neighborhood, chief among them her indomitable mother. “I absorbed them as I would chloroform on a cloth laid against my face. It has taken me 30 years to understand how much of them I understood.”

“I remember only the women,” Vivian Gornick writes near the start of her memoir of growing up in the Bronx tenements in the 1940s, surrounded by the blunt, brawling, yearning women of the neighborhood, chief among them her indomitable mother. “I absorbed them as I would chloroform on a cloth laid against my face. It has taken me 30 years to understand how much of them I understood.” With the ability to use tools, solve complex puzzles, and even

With the ability to use tools, solve complex puzzles, and even  The photos of

The photos of