Jenni Quilter at the TLS:

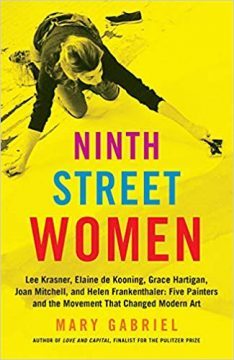

Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women charts the rise of five female Abstract Expressionist painters in New York – Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler – which is a bold move, since all of these women expressed vehement dislike of critics who used their gender as an ordering conceit. To be labelled a “lady painter” or the “wife of the artist” was an exoticization at best, a dismissal at worst. In 1957, Hartigan, Mitchell and Frankenthaler were featured in Life magazine’s feature “Women Artists in Ascendance”, photographed in their studios with their work. Each looks steadily at the camera. They knew the possible benefits of exposure, but they didn’t have to smile. In her introduction, Gabriel tells us that what she has written, “through the biographies of five remarkable women, is the story of a cultural revolution that occurred between the years of 1929 and 1959 as it arose out of the Depression and the Second World War, developed amid the Cold War and McCarthyism, and declined through the early boom years of America’s consumer culture”. Well, yes, but beyond these larger, sweeping assessments of society and gender there is a lot more.

Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women charts the rise of five female Abstract Expressionist painters in New York – Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler – which is a bold move, since all of these women expressed vehement dislike of critics who used their gender as an ordering conceit. To be labelled a “lady painter” or the “wife of the artist” was an exoticization at best, a dismissal at worst. In 1957, Hartigan, Mitchell and Frankenthaler were featured in Life magazine’s feature “Women Artists in Ascendance”, photographed in their studios with their work. Each looks steadily at the camera. They knew the possible benefits of exposure, but they didn’t have to smile. In her introduction, Gabriel tells us that what she has written, “through the biographies of five remarkable women, is the story of a cultural revolution that occurred between the years of 1929 and 1959 as it arose out of the Depression and the Second World War, developed amid the Cold War and McCarthyism, and declined through the early boom years of America’s consumer culture”. Well, yes, but beyond these larger, sweeping assessments of society and gender there is a lot more.

more here.

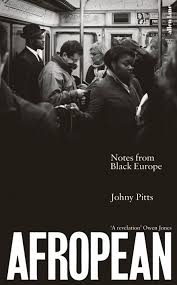

At a time where politicians across the world are calling for ever more secure borders, there are books whose mere existence feels radical. Afropean: Notes from Black Europe, by Johny Pitts, feels like one such publication. It is the story of the Sheffield-born author’s travel from his home town across the Continent, visiting several of its major cities and connecting – or not – with people of African heritage as he goes. Crucially, it is also the story of Pitts’s internal journey, to find where he, a working-class, mixed-race man from the north of England, might fit most comfortably within Europe’s complex past and its possibly chaotic future.

At a time where politicians across the world are calling for ever more secure borders, there are books whose mere existence feels radical. Afropean: Notes from Black Europe, by Johny Pitts, feels like one such publication. It is the story of the Sheffield-born author’s travel from his home town across the Continent, visiting several of its major cities and connecting – or not – with people of African heritage as he goes. Crucially, it is also the story of Pitts’s internal journey, to find where he, a working-class, mixed-race man from the north of England, might fit most comfortably within Europe’s complex past and its possibly chaotic future. Remember when everyone left doors unlocked and borrowed cups of sugar? No? Then this richly researched history of community may well appeal. Jon Lawrence uncovers the reality behind romantic cliches of our postwar past. He convincingly suggests that the real history of community is one in which people have combined solidarity with self-reliance and privacy.

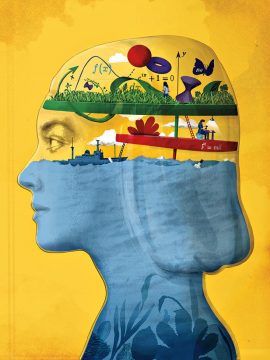

Remember when everyone left doors unlocked and borrowed cups of sugar? No? Then this richly researched history of community may well appeal. Jon Lawrence uncovers the reality behind romantic cliches of our postwar past. He convincingly suggests that the real history of community is one in which people have combined solidarity with self-reliance and privacy. Personalized medicine. Precision medicine. Genomic medicine. Individualized medicine. All of these phrases strive to express a similar vision—a reality where physicians treat based on each patient’s unique biology. The concept is poised to revolutionize clinical and preventive care. But even as the technologies helping to birth this new breed of medicine mature, the semantics surrounding the phenomenon are still experiencing growing pains. So, what should we call it? For a long time, “personalized medicine” was the preferred nomenclature. In the popular press especially, this was (and often still is) the go-to phrase to describe the medical paradigm shift that is underway. But about eight years ago, a committee convened by the director of the National Institutes of Health

Personalized medicine. Precision medicine. Genomic medicine. Individualized medicine. All of these phrases strive to express a similar vision—a reality where physicians treat based on each patient’s unique biology. The concept is poised to revolutionize clinical and preventive care. But even as the technologies helping to birth this new breed of medicine mature, the semantics surrounding the phenomenon are still experiencing growing pains. So, what should we call it? For a long time, “personalized medicine” was the preferred nomenclature. In the popular press especially, this was (and often still is) the go-to phrase to describe the medical paradigm shift that is underway. But about eight years ago, a committee convened by the director of the National Institutes of Health  Two and a half years ago, feeling existentially adrift about the future of the planet, I sent a letter to Wendell Berry, hoping he might have answers. Berry has published more than eighty books of poetry, fiction, essays, and criticism, but he’s perhaps best known for “

Two and a half years ago, feeling existentially adrift about the future of the planet, I sent a letter to Wendell Berry, hoping he might have answers. Berry has published more than eighty books of poetry, fiction, essays, and criticism, but he’s perhaps best known for “ As you may have heard, I have a new book coming out in September,

As you may have heard, I have a new book coming out in September,  Officials eyeing you with contempt. Police treating you as scum. A sense of being constantly watched and judged by professionals. Living in fear of benefit sanctions. A lack of community facilities.

Officials eyeing you with contempt. Police treating you as scum. A sense of being constantly watched and judged by professionals. Living in fear of benefit sanctions. A lack of community facilities. W

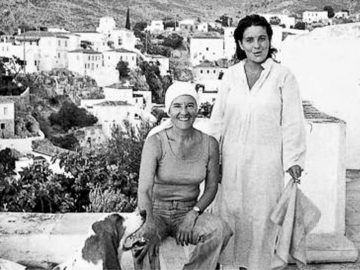

W “That summer we bought big straw hats. Maria’s had cherries around the rim, Infanta’s had forget-me-nots, and mine had poppies as red as fire. When we lay in the hayfield wearing them, the sky, the wildflowers, and the three of us all melted into one.” The beginning of Margarita Liberaki’s Three Summers, at once vivid and hazy, evokes the season and the story of adolescent girlhood that the book will unfold. The novel tells the story of three sisters living outside Athens: Maria, Infanta, and Katerina, the youngest, who tells the tale. The house where they live with their mother, aunt, and grandfather is in the countryside. Focusing on the sisters’ daily life and first loves, as well as on a secret about their Polish grandmother, the novel is about growing up and how strange and exciting it is to discover the curious moods and desires that constitute you and your difference from other people. It also features a stable cast of friends and neighbors, all with their own unexpected opinions: the self-involved Laura Parigori; the studious astronomer David and his Jewish mother, Ruth, from England; and the carefree Captain Andreas. The book is adventurous, fantastical, romantic, down to earth, earthy, and, above all, warm. Its only season, after all, is summer.

“That summer we bought big straw hats. Maria’s had cherries around the rim, Infanta’s had forget-me-nots, and mine had poppies as red as fire. When we lay in the hayfield wearing them, the sky, the wildflowers, and the three of us all melted into one.” The beginning of Margarita Liberaki’s Three Summers, at once vivid and hazy, evokes the season and the story of adolescent girlhood that the book will unfold. The novel tells the story of three sisters living outside Athens: Maria, Infanta, and Katerina, the youngest, who tells the tale. The house where they live with their mother, aunt, and grandfather is in the countryside. Focusing on the sisters’ daily life and first loves, as well as on a secret about their Polish grandmother, the novel is about growing up and how strange and exciting it is to discover the curious moods and desires that constitute you and your difference from other people. It also features a stable cast of friends and neighbors, all with their own unexpected opinions: the self-involved Laura Parigori; the studious astronomer David and his Jewish mother, Ruth, from England; and the carefree Captain Andreas. The book is adventurous, fantastical, romantic, down to earth, earthy, and, above all, warm. Its only season, after all, is summer. Many poets

Many poets Nothing belongs to us any more; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand. They will even take away our name: and if we want to keep it, we will have to find our strength to do so, to manage somehow so that behind the name something of us, of us as we were, still remains.” So

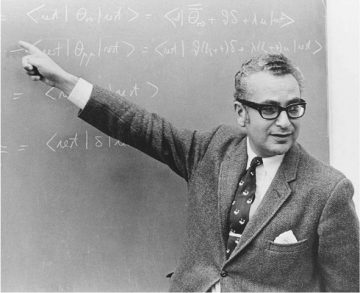

Nothing belongs to us any more; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand. They will even take away our name: and if we want to keep it, we will have to find our strength to do so, to manage somehow so that behind the name something of us, of us as we were, still remains.” So  I was a wayward kid who grew up on the literary side of life, treating math and science as if they were pustules from the plague. So it’s a little strange how I’ve ended up now—someone who dances daily with triple integrals, Fourier transforms, and that crown jewel of mathematics, Euler’s equation. It’s hard to believe I’ve flipped from a virtually congenital math-phobe to a professor of engineering. One day, one of my students asked me how I did it—how I changed my brain. I wanted to answer Hell—with lots of difficulty! After all, I’d flunked my way through elementary, middle, and high school math and science. In fact, I didn’t start studying remedial math until I left the Army at age 26. If there were a textbook example of the potential for adult neural plasticity, I’d be Exhibit A.

I was a wayward kid who grew up on the literary side of life, treating math and science as if they were pustules from the plague. So it’s a little strange how I’ve ended up now—someone who dances daily with triple integrals, Fourier transforms, and that crown jewel of mathematics, Euler’s equation. It’s hard to believe I’ve flipped from a virtually congenital math-phobe to a professor of engineering. One day, one of my students asked me how I did it—how I changed my brain. I wanted to answer Hell—with lots of difficulty! After all, I’d flunked my way through elementary, middle, and high school math and science. In fact, I didn’t start studying remedial math until I left the Army at age 26. If there were a textbook example of the potential for adult neural plasticity, I’d be Exhibit A.

This genetic explanation of my Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry came as no surprise. According to family lore, my forebears lived in small towns and villages in eastern Europe for at least a few hundred years, where they kept their traditions and married within the community, up until the Holocaust, when they were either murdered or dispersed.

This genetic explanation of my Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry came as no surprise. According to family lore, my forebears lived in small towns and villages in eastern Europe for at least a few hundred years, where they kept their traditions and married within the community, up until the Holocaust, when they were either murdered or dispersed.

Almost all books of aphorisms, which have ever acquired a reputation, have retained it,” John Stuart Mill wrote in 1837, aphoristically—that is to say, with a neat if slightly dubious finality. (“How wofully the reverse is the case with systems of philosophy,” he added.) We prefer collections of aphorisms over big books of philosophy, Mill thought, not just because the contents are always short and usually funny but because the aphorism is, in its algebraic abbreviation, a micro-model of empirical inquiry. Mill noted that “to be unsystematic is of the essence of all truths which rest on specific experiment,” and that there is, in a good aphorism, “generally truth, or a bold approach to some truth.” So when La Rochefoucauld writes, “In the misfortune of even our best friends, there is something that does not displease us,” he is offering not a moral injunction saying “Take pleasure in the misfortune of your best friends” but a testable observation about what Mill termed “the workings of habitual selfishness in the human breast.” The aphorism means: We do take pleasure—not in every case, perhaps, but more often than we might admit—in the misfortune of our best friends.

Almost all books of aphorisms, which have ever acquired a reputation, have retained it,” John Stuart Mill wrote in 1837, aphoristically—that is to say, with a neat if slightly dubious finality. (“How wofully the reverse is the case with systems of philosophy,” he added.) We prefer collections of aphorisms over big books of philosophy, Mill thought, not just because the contents are always short and usually funny but because the aphorism is, in its algebraic abbreviation, a micro-model of empirical inquiry. Mill noted that “to be unsystematic is of the essence of all truths which rest on specific experiment,” and that there is, in a good aphorism, “generally truth, or a bold approach to some truth.” So when La Rochefoucauld writes, “In the misfortune of even our best friends, there is something that does not displease us,” he is offering not a moral injunction saying “Take pleasure in the misfortune of your best friends” but a testable observation about what Mill termed “the workings of habitual selfishness in the human breast.” The aphorism means: We do take pleasure—not in every case, perhaps, but more often than we might admit—in the misfortune of our best friends.