Anechoic

George Foy stayed in the anechoic chamber

for 45 minutes and nearly went mad.

He could hear the blood rushing in

his veins and began to wonder if he was

hallucinating. He had been to a monastery,

an American Indian sweat lodge,

and a nickel mine two kilometers underground.

In the anechoic chamber, the floor’s design

eliminates the sound of footsteps.

NASA trains astronauts in anechoic chambers

to cope with the silence of space.

Without echo, in the quietest place on earth,

what else can we hold onto? What replaces sound

in concert with what you see? The human voice,

the timber when a person says kamsahamnida

or yes, please, or fuerte, is 25 to 35 decibels.

Hearing damage can start around 115 decibels.

Metallica, front row, possible damage

albeit possible love. The Who, 126 decibels.

A Boeing jet, 165 decibels. The whale, low rumble

frequency and all, 188 decibels, can be heard

for hundreds of miles underwater.

I once walked around inside a whale heart,

which is the size of a small car. The sound

was like Brian Doyle’s heart that gave out

at 60 after he wrote my favorite essay

about the joyas voladoras and the humming

bird heart, the whale heart, and the human

heart. Glass can break at 163 decibels.

Hearing is the last sense to leave us.

Some say that upon death, our vision,

our taste, our touch, and our smell

might leave us, but some have been

pronounced dead and by all indication

are, but they can hear. In this moment,

when the doctor pronounces the time

or when the handgun pumps once more,

what light arrives? What sounds, the angels?

The Ultrasonic Weapon is used for crowd

control or to combat riots—as too many

humans gathered in one place for a unified

purpose can threaten the state. The state

permits gatherings if the flag waves. Sound

can be weaponized or made into art.

It can kill. It can heal a wound. It is

a navigation device and can help determine

if the woman has a second heart inside of her

now, the beating heart of a baby on the ultrasound,

a boy or a girl, making a new music in the body

of another body, a chorus, a concert, a hush.

by Lee Herrick

from Scar and Flower

Word Poetry, 2019

Mainstream philosophy and science at least since Aristotle have held to the view that each living body, under normal circumstances, should be inhabited by no more than one soul. If you don’t care for talk of souls, exchange that word for “individual”, and the point still stands: sharing bodily space is abnormal, a sign of pathology, to be corrected by flushing the worms out of your entrails, or by mulesing your sheep against flystrike.

Mainstream philosophy and science at least since Aristotle have held to the view that each living body, under normal circumstances, should be inhabited by no more than one soul. If you don’t care for talk of souls, exchange that word for “individual”, and the point still stands: sharing bodily space is abnormal, a sign of pathology, to be corrected by flushing the worms out of your entrails, or by mulesing your sheep against flystrike.

The Beatles

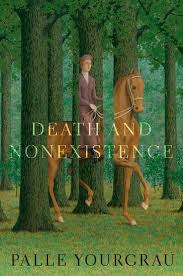

The Beatles To choose another prominent example, consider what Francis Kamm writes in Morality, Mortality: “Life can sometimes be worse for a person than the alternative of nonexistence, even though nonexistence is not a better state of being.” For Kamm, nonexistence is never a better state of being than is existence because for her, apparently, nonexistence is not a state of being at all.

To choose another prominent example, consider what Francis Kamm writes in Morality, Mortality: “Life can sometimes be worse for a person than the alternative of nonexistence, even though nonexistence is not a better state of being.” For Kamm, nonexistence is never a better state of being than is existence because for her, apparently, nonexistence is not a state of being at all. “The Odyssey” by Homer

“The Odyssey” by Homer Whether you’re talking about the polyrhythmic complexity of bands like the Talking Heads, the understated virtuosity of Television’s Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine, or even the deep chops of drummer Marc “Marky Ramone” Bell (Dust, Voidoids, Ramones), the punk scene was a wellspring of talent. Punk’s focus, for the most part, was song-centric and eschewed extended jamming, and the scene’s musicians prized restraint, as opposed to flash. But ability—despite their short hair, leather, and safety pins—wasn’t lacking. They were a reaction to the milquetoast fluff on popular radio (Debbie Boone, the Eagles), and took pains to distinguish themselves as misfits. But even the punks had their outliers, and a prominent delegate was guitarist Robert Quine.

Whether you’re talking about the polyrhythmic complexity of bands like the Talking Heads, the understated virtuosity of Television’s Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine, or even the deep chops of drummer Marc “Marky Ramone” Bell (Dust, Voidoids, Ramones), the punk scene was a wellspring of talent. Punk’s focus, for the most part, was song-centric and eschewed extended jamming, and the scene’s musicians prized restraint, as opposed to flash. But ability—despite their short hair, leather, and safety pins—wasn’t lacking. They were a reaction to the milquetoast fluff on popular radio (Debbie Boone, the Eagles), and took pains to distinguish themselves as misfits. But even the punks had their outliers, and a prominent delegate was guitarist Robert Quine. If every philosopher has a home that is not a house – the mountains, the sea, the city streets – for Martin Heidegger, it was the Black Forest. This sprawling woodland, situated by the French border in south-west Germany, imbued Heidegger’s language – his writings are filled with references to “forest paths”, “waymarks” and “clearings” – and shaped his thought. There, in the solitude of his small wood cabin, he wrote his great work, Being and Time.

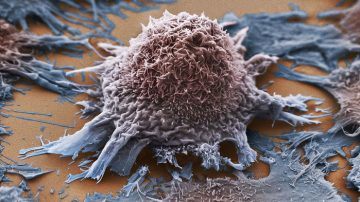

If every philosopher has a home that is not a house – the mountains, the sea, the city streets – for Martin Heidegger, it was the Black Forest. This sprawling woodland, situated by the French border in south-west Germany, imbued Heidegger’s language – his writings are filled with references to “forest paths”, “waymarks” and “clearings” – and shaped his thought. There, in the solitude of his small wood cabin, he wrote his great work, Being and Time. Cancer drug developers may be missing their molecular targets—and never knowing it. Many recent drugs take aim at specific cell proteins that drive the growth of tumors. The strategy has had marked successes, such as the leukemia drug Gleevec. But a study now finds that numerous candidate anticancer drugs still kill tumor cells after the genome editor CRISPR was used to eliminate their presumed targets. That suggests the drugs thwart cancer by interacting with different molecules than intended. The study,

Cancer drug developers may be missing their molecular targets—and never knowing it. Many recent drugs take aim at specific cell proteins that drive the growth of tumors. The strategy has had marked successes, such as the leukemia drug Gleevec. But a study now finds that numerous candidate anticancer drugs still kill tumor cells after the genome editor CRISPR was used to eliminate their presumed targets. That suggests the drugs thwart cancer by interacting with different molecules than intended. The study,  You started out being dismissed by the literary establishment as a lowly peddler of cheap horror. You’re now a lauded national treasure. How does it feel to be respectable?

You started out being dismissed by the literary establishment as a lowly peddler of cheap horror. You’re now a lauded national treasure. How does it feel to be respectable? Artificial intelligence has a trust problem. We are relying on A.I. more and more, but it hasn’t yet earned our confidence.

Artificial intelligence has a trust problem. We are relying on A.I. more and more, but it hasn’t yet earned our confidence. Those in the harm reduction world know Portugal as a harm reduction Mecca: renowned for its 2001 legislation that decriminalized possession of small amounts of substances—including “hard” drugs like heroin and cocaine—and prioritized the health and human rights of people who use drugs over punishing them for it.

Those in the harm reduction world know Portugal as a harm reduction Mecca: renowned for its 2001 legislation that decriminalized possession of small amounts of substances—including “hard” drugs like heroin and cocaine—and prioritized the health and human rights of people who use drugs over punishing them for it. The basic function of a doorbell is to facilitate a call and response through walls. Depressing the button, the visitor closes an electrical circuit, sending a signal through the infrastructure toward a piece of hardware that emits noise in the chosen room. In a multi-apartment building, the resident, now aware of the presence of an unseen visitor on the threshold, can press a button that sends a current back downstairs, releasing the door’s lock.

The basic function of a doorbell is to facilitate a call and response through walls. Depressing the button, the visitor closes an electrical circuit, sending a signal through the infrastructure toward a piece of hardware that emits noise in the chosen room. In a multi-apartment building, the resident, now aware of the presence of an unseen visitor on the threshold, can press a button that sends a current back downstairs, releasing the door’s lock. DURING THE DAY,

DURING THE DAY, With the coming of the Third Reich, Nolde let the mask drop completely. He not only denounced his fellow artist Pechstein as a “Jew” (he wasn’t), but in the summer of 1933 drafted a plan, which he later destroyed, for how to remove Jews from German society. And unfortunately for him, plenty of other evidence has survived. In the autumn of 1938, for example, Nolde wrote that one could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”. In November 1940, he praised Hitler’s speech on the anniversary of the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, especially the passages attacking “the Jews”.

With the coming of the Third Reich, Nolde let the mask drop completely. He not only denounced his fellow artist Pechstein as a “Jew” (he wasn’t), but in the summer of 1933 drafted a plan, which he later destroyed, for how to remove Jews from German society. And unfortunately for him, plenty of other evidence has survived. In the autumn of 1938, for example, Nolde wrote that one could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”. In November 1940, he praised Hitler’s speech on the anniversary of the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, especially the passages attacking “the Jews”. About a century ago, a series of giant murals was unveiled in the Palace of Westminster depicting the “

About a century ago, a series of giant murals was unveiled in the Palace of Westminster depicting the “ The other day I fixed something—a rarity for me. The flotation device in the toilet water tank was rubbing against the side, getting stuck halfway up so that the tank didn’t fill completely. I own a hammer and know how to operate it. But I couldn’t fit it into the tank to whack the device back into place. Ditto for owning and using a wrench. It wouldn’t fit either. But fortunately I also own a plunger and I used its handle to push the floating thing back the other way, using the side of the tank as a fulcrum. It worked, although the device got bent so that the top of the tank didn’t quite fit. That overwhelmed me, so I called it a good day’s work. I was proud of myself. “There,” I thought smugly. “It’s not just chimps who can use tools.”

The other day I fixed something—a rarity for me. The flotation device in the toilet water tank was rubbing against the side, getting stuck halfway up so that the tank didn’t fill completely. I own a hammer and know how to operate it. But I couldn’t fit it into the tank to whack the device back into place. Ditto for owning and using a wrench. It wouldn’t fit either. But fortunately I also own a plunger and I used its handle to push the floating thing back the other way, using the side of the tank as a fulcrum. It worked, although the device got bent so that the top of the tank didn’t quite fit. That overwhelmed me, so I called it a good day’s work. I was proud of myself. “There,” I thought smugly. “It’s not just chimps who can use tools.”