Snigdha Poonam in MIL:

When he’s doing his dance, Israil Ansari looks like a tornado. Keeping his feet pinned to the ground, he bends his elbows and knees and moves his arms and legs from side to side at such a high speed that his body and immediate surroundings dissolve into a blur. It’s a dance that divides opinion. His fans describe him as a “unique talent” and “the world’s eighth wonder”. He has more than 2m followers on TikTok, the video-sharing app that made his name. But his detractors don’t hold back: “I can’t bear to watch this”, “someone take this guy to a hospital”, “give us a break, bro”. Ansari says he is happy as long as people are watching. “Fifty percent of it is love, fifty percent of it is hate. I will take both.” Naturally, he prefers the love, although it can get a bit much. In Mumbai people stop him in the street. They ask for a selfie, then they ask him to do the dance. He always obliges, but when he’s in a hurry he wears a cap to avoid being ambushed. Without it, Ansari can be spotted a mile off because of his hair, which is almost as crazy as his dance. It’s currently green at the front and blond at the back, although it won’t be for long. He likes to dye it to match his clothes. “In one month I have changed my hair colour 27 times. No one else has done that in the world.”

When he’s doing his dance, Israil Ansari looks like a tornado. Keeping his feet pinned to the ground, he bends his elbows and knees and moves his arms and legs from side to side at such a high speed that his body and immediate surroundings dissolve into a blur. It’s a dance that divides opinion. His fans describe him as a “unique talent” and “the world’s eighth wonder”. He has more than 2m followers on TikTok, the video-sharing app that made his name. But his detractors don’t hold back: “I can’t bear to watch this”, “someone take this guy to a hospital”, “give us a break, bro”. Ansari says he is happy as long as people are watching. “Fifty percent of it is love, fifty percent of it is hate. I will take both.” Naturally, he prefers the love, although it can get a bit much. In Mumbai people stop him in the street. They ask for a selfie, then they ask him to do the dance. He always obliges, but when he’s in a hurry he wears a cap to avoid being ambushed. Without it, Ansari can be spotted a mile off because of his hair, which is almost as crazy as his dance. It’s currently green at the front and blond at the back, although it won’t be for long. He likes to dye it to match his clothes. “In one month I have changed my hair colour 27 times. No one else has done that in the world.”

Ansari is 19 and comes from a village in Uttar Pradesh in northern India, one of the poorest parts of the country. Until recently, he lived with his parents, grandparents and 11 siblings. His family couldn’t afford to keep him in school over the age of ten, so he dropped out and started working at a hardware store, supplementing his income with odd jobs, like painting houses or tiling. In 2017 he was at a wedding when a friend with a smartphone showed him TikTok, whose users post short, lo-fi videos of themselves doing just about anything: lip-syncing to pop music, conducting make-up tutorials, standing on their head. He was sold. “People were just expressing themselves. I thought: I could do that as well.”

He asked his brother, who works in a factory in Gujarat, to send him a smartphone. Then he started experimenting with TikTok. He made a few videos of himself joking around but failed to get much traction. Then one day in May 2018 he was walking through paddy fields listening to Bollywood tunes on his phone when a song featuring the actor Shah Rukh Khan began to play. He describes how, possessed by the music, he started to dance in a way no one had ever danced before: “This dance was just not there. Not in Bollywood films, not in the music videos. I brought it to the market,” he says, sweeping his hair back from his face.

More here.

Stephen King’s protagonists have been hunted by all sorts of malevolent beings, from the demonic clown of “It” to the fiendish cowboy Randall Flagg in “

Stephen King’s protagonists have been hunted by all sorts of malevolent beings, from the demonic clown of “It” to the fiendish cowboy Randall Flagg in “ HUMEYSHA: There’s a line from Grandmaster Flash about how hip-hop pioneers would “adopt” from the history of music by taking a few seconds of a groove, playing it on repeat, and finding a rhythm for audiences to dance to. Whether it’s with a few bars from a qawwali recording or my guitar experiments, I think I’ve always been in love with the sampling technique for how it embodies a very contemporary way we make our selves. To intimately know histories of music, dig through the archives, and identify passages that loop seamlessly, without clicks or pops where the endings match the beginning—it’s a tool of infinite possibility despite being constrained by a strict sense of time and bound up with material. People like you and I assert how we are similarly not fixed, static identities bound only by our inheritance or biology; what matters is what we do with it, by remixing past to remake ourselves anew. I am not just where I come from or where I reside, but also all I’ve invested in. And as a musician that’s why I draw on sounds from all the places I lived in to voice new ones that feel more like home.

HUMEYSHA: There’s a line from Grandmaster Flash about how hip-hop pioneers would “adopt” from the history of music by taking a few seconds of a groove, playing it on repeat, and finding a rhythm for audiences to dance to. Whether it’s with a few bars from a qawwali recording or my guitar experiments, I think I’ve always been in love with the sampling technique for how it embodies a very contemporary way we make our selves. To intimately know histories of music, dig through the archives, and identify passages that loop seamlessly, without clicks or pops where the endings match the beginning—it’s a tool of infinite possibility despite being constrained by a strict sense of time and bound up with material. People like you and I assert how we are similarly not fixed, static identities bound only by our inheritance or biology; what matters is what we do with it, by remixing past to remake ourselves anew. I am not just where I come from or where I reside, but also all I’ve invested in. And as a musician that’s why I draw on sounds from all the places I lived in to voice new ones that feel more like home. Fredson Bowers didn’t know what he would find when he began digging into the disordered stack of 230 loose pages—all from 19th-century Walt Whitman manuscripts—that landed on his desk in 1951.

Fredson Bowers didn’t know what he would find when he began digging into the disordered stack of 230 loose pages—all from 19th-century Walt Whitman manuscripts—that landed on his desk in 1951. In 2010, physicists in Germany

In 2010, physicists in Germany  Binyamin Appelbaum’s new book has lived up to its controversial billing, particularly among its subjects. The book condemns the role the economics profession has played in breeding inequality, and holds economists to account for the resulting backlash of xenophobic white nationalism. When the New York Times published

Binyamin Appelbaum’s new book has lived up to its controversial billing, particularly among its subjects. The book condemns the role the economics profession has played in breeding inequality, and holds economists to account for the resulting backlash of xenophobic white nationalism. When the New York Times published  Viola’s film I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like (1986), its title a loose translation of a Sanskrit verse from the Rig-Veda, serves as the intellectual and spiritual touchstone of the exhibit. Eighty-nine minutes long, it unfolds as a wordless odyssey, an epic quest for self-understanding and transcendence that ranges from mountain lakes and underground caves to grassy fields and remote islands. Viola contemplates the cryptic gazes of wild animals (mostly fish and birds, but also a pair of bison, a zebra, and an elephant); takes us inside his studio (playfully modeled on seventeenth-century Dutch still-lifes); leads us through an intense, violent sequence filled with split-second flashes of lightning, crowded highways, and roaring flames; then drops us down in the middle of a raucous firewalking ritual in Fiji, the soundtrack filled with beating drums and wailing wind instruments. The film concludes in a forest, close to the lake where we began.

Viola’s film I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like (1986), its title a loose translation of a Sanskrit verse from the Rig-Veda, serves as the intellectual and spiritual touchstone of the exhibit. Eighty-nine minutes long, it unfolds as a wordless odyssey, an epic quest for self-understanding and transcendence that ranges from mountain lakes and underground caves to grassy fields and remote islands. Viola contemplates the cryptic gazes of wild animals (mostly fish and birds, but also a pair of bison, a zebra, and an elephant); takes us inside his studio (playfully modeled on seventeenth-century Dutch still-lifes); leads us through an intense, violent sequence filled with split-second flashes of lightning, crowded highways, and roaring flames; then drops us down in the middle of a raucous firewalking ritual in Fiji, the soundtrack filled with beating drums and wailing wind instruments. The film concludes in a forest, close to the lake where we began. The book is “an autobiographical account of what it is like to have a body in a specific time and place,” to borrow Boyer’s description of Hieroi Logoi (Sacred Tales) by the second-century Greek orator Aelius Aristides, one of many texts and artworks about illness and pain that Boyer references, quotes from, and argues with, placing her writing in their lineage. The prologue to The Undying explains what makes her specific time and place—and the literary forms they demand—different from those of breast cancer patients who came before. When Fanny Burney described her pre-anesthesia mastectomy in a 1812 letter to her sister, she was articulating a rare experience at the great personal cost of reliving the nearly unbearable. When Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals were published in 1980, her first-person account of cancer rippled through a surrounding quiet. Until more recently, people didn’t often discuss their diagnoses in public. Susan Sontag and Rachel Carson each had breast cancer, yet wrote about cancer without addressing their own.

The book is “an autobiographical account of what it is like to have a body in a specific time and place,” to borrow Boyer’s description of Hieroi Logoi (Sacred Tales) by the second-century Greek orator Aelius Aristides, one of many texts and artworks about illness and pain that Boyer references, quotes from, and argues with, placing her writing in their lineage. The prologue to The Undying explains what makes her specific time and place—and the literary forms they demand—different from those of breast cancer patients who came before. When Fanny Burney described her pre-anesthesia mastectomy in a 1812 letter to her sister, she was articulating a rare experience at the great personal cost of reliving the nearly unbearable. When Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals were published in 1980, her first-person account of cancer rippled through a surrounding quiet. Until more recently, people didn’t often discuss their diagnoses in public. Susan Sontag and Rachel Carson each had breast cancer, yet wrote about cancer without addressing their own. How to affirm life in the face of suffering, sacrifice and likely failure may have the structure of a question, but, like the apparent questions of who we are and what we are here for, it is far from obvious that what we are meant to do with it is to search for an answer, let alone settle on one. To affirm life is not to give a theoretical justification of life, to acknowledge its merits and counter the charges of its detractors. To affirm life is to live, and to do so in a certain way: committing to projects and relationships, assuming responsibility, allowing things to matter to you. Bringing a child into the world is not the only way to affirm life—Heti’s narrator, for one, chooses art—but it is the most basic. This is not only because bringing forth and nurturing life is the most literal way of affirming it, but because parenting is the greatest responsibility a human can bear toward another.

How to affirm life in the face of suffering, sacrifice and likely failure may have the structure of a question, but, like the apparent questions of who we are and what we are here for, it is far from obvious that what we are meant to do with it is to search for an answer, let alone settle on one. To affirm life is not to give a theoretical justification of life, to acknowledge its merits and counter the charges of its detractors. To affirm life is to live, and to do so in a certain way: committing to projects and relationships, assuming responsibility, allowing things to matter to you. Bringing a child into the world is not the only way to affirm life—Heti’s narrator, for one, chooses art—but it is the most basic. This is not only because bringing forth and nurturing life is the most literal way of affirming it, but because parenting is the greatest responsibility a human can bear toward another. To be a

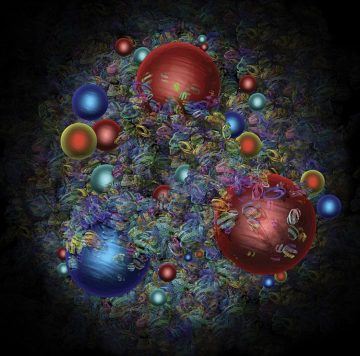

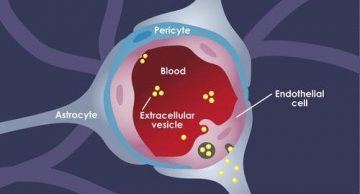

To be a  Metastasizing breast cancers typically seek out the bones, lung, and brain. Brain metastases are especially dangerous; many women survive for less than a year after diagnosis. How is the cancer able to get past the blood brain barrier? And can it be blocked? Those questions led Ph.D. candidate Golnaz Morad, DDS, and her mentor Marsha Moses, Ph.D., to conduct an in-depth investigation of exosomes, also known as extracellular vesicles or EVs, and their role in breast-to-

Metastasizing breast cancers typically seek out the bones, lung, and brain. Brain metastases are especially dangerous; many women survive for less than a year after diagnosis. How is the cancer able to get past the blood brain barrier? And can it be blocked? Those questions led Ph.D. candidate Golnaz Morad, DDS, and her mentor Marsha Moses, Ph.D., to conduct an in-depth investigation of exosomes, also known as extracellular vesicles or EVs, and their role in breast-to- Mainstream philosophy and science at least since Aristotle have held to the view that each living body, under normal circumstances, should be inhabited by no more than one soul. If you don’t care for talk of souls, exchange that word for “individual”, and the point still stands: sharing bodily space is abnormal, a sign of pathology, to be corrected by flushing the worms out of your entrails, or by mulesing your sheep against flystrike.

Mainstream philosophy and science at least since Aristotle have held to the view that each living body, under normal circumstances, should be inhabited by no more than one soul. If you don’t care for talk of souls, exchange that word for “individual”, and the point still stands: sharing bodily space is abnormal, a sign of pathology, to be corrected by flushing the worms out of your entrails, or by mulesing your sheep against flystrike.

The Beatles

The Beatles To choose another prominent example, consider what Francis Kamm writes in Morality, Mortality: “Life can sometimes be worse for a person than the alternative of nonexistence, even though nonexistence is not a better state of being.” For Kamm, nonexistence is never a better state of being than is existence because for her, apparently, nonexistence is not a state of being at all.

To choose another prominent example, consider what Francis Kamm writes in Morality, Mortality: “Life can sometimes be worse for a person than the alternative of nonexistence, even though nonexistence is not a better state of being.” For Kamm, nonexistence is never a better state of being than is existence because for her, apparently, nonexistence is not a state of being at all. “The Odyssey” by Homer

“The Odyssey” by Homer