Jocelyn Kaiser in Science:

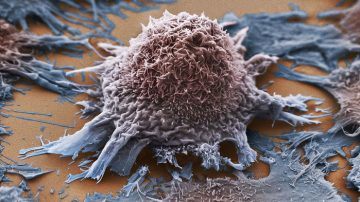

Cancer drug developers may be missing their molecular targets—and never knowing it. Many recent drugs take aim at specific cell proteins that drive the growth of tumors. The strategy has had marked successes, such as the leukemia drug Gleevec. But a study now finds that numerous candidate anticancer drugs still kill tumor cells after the genome editor CRISPR was used to eliminate their presumed targets. That suggests the drugs thwart cancer by interacting with different molecules than intended. The study, published this week in Science Translational Medicine, points to problems with an older lab tool for silencing genes that has been used to identify leads for such drugs. The results also hint that the drugs in question, most of which are in clinical trials, and perhaps others could be optimized to work even better by pinning down their true mechanism. “The work is very well done and it’s a great public service. I hope people talk about it. I don’t find any of it surprising, unfortunately,” says William Kaelin of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, who has written about why promising preclinical findings are often not reproducible, or fail to lead to drugs.

Cancer drug developers may be missing their molecular targets—and never knowing it. Many recent drugs take aim at specific cell proteins that drive the growth of tumors. The strategy has had marked successes, such as the leukemia drug Gleevec. But a study now finds that numerous candidate anticancer drugs still kill tumor cells after the genome editor CRISPR was used to eliminate their presumed targets. That suggests the drugs thwart cancer by interacting with different molecules than intended. The study, published this week in Science Translational Medicine, points to problems with an older lab tool for silencing genes that has been used to identify leads for such drugs. The results also hint that the drugs in question, most of which are in clinical trials, and perhaps others could be optimized to work even better by pinning down their true mechanism. “The work is very well done and it’s a great public service. I hope people talk about it. I don’t find any of it surprising, unfortunately,” says William Kaelin of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, who has written about why promising preclinical findings are often not reproducible, or fail to lead to drugs.

Leads for many recent targeted drugs emerged from experiments in which cancer cells were dosed with RNA strands that disrupt the natural RNAs that convey a gene’s protein-building instructions. After using this RNA interference (RNAi) method to zero in on genes essential to the growth of cancer cells, researchers screened libraries of molecules to find compounds that block the genes’ proteins.

More here.