Mikaella Clements at the TLS:

Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors.

Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors.

Part of the dream of a good bath is its isolation. If someone else does arrive, you can hope that the intrusion is at the very least a sexy one. Hedger and Eden in Willa Cather’s Coming, Aphrodite live in the same apartment block and meet just outside the communal bathroom, but it’s not quite the sensual interaction one might aspire to: “I’ve found his hair in the tub, and I’ve smelled a doggy smell, and now I’ve caught you at it. It’s an outrage!” says Eden, realizing that Hedger washes his English bulldog in their shared tub.

more here.

The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001.

The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001. In November 1959 aged 26,

In November 1959 aged 26,  Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow

Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow  Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

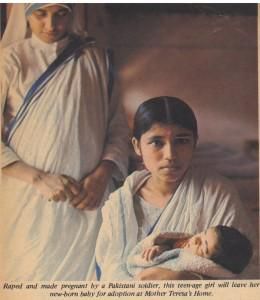

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India.

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India. Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”

Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”

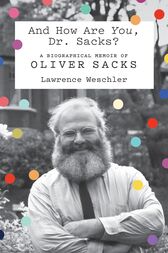

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.”

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.” Brexit

Brexit A

A In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth.

In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth. Physicists study systems that are sufficiently simple that it’s possible to find deep unifying principles applicable to all situations. In psychology or sociology that’s a lot harder. But as I say at the end of this episode, Mindscape is a safe space for grand theories of everything. Psychologist Michele Gelfand claims that there’s a single dimension that captures a lot about how cultures differ: a spectrum between “tight” and “loose,” referring to the extent to which social norms are automatically respected. Oregon is loose; Alabama is tight. Italy is loose; Singapore is tight. It’s a provocative thesis, back up by copious amounts of data, that could shed light on human behavior not only in different parts of the world, but in different settings at work or at school.

Physicists study systems that are sufficiently simple that it’s possible to find deep unifying principles applicable to all situations. In psychology or sociology that’s a lot harder. But as I say at the end of this episode, Mindscape is a safe space for grand theories of everything. Psychologist Michele Gelfand claims that there’s a single dimension that captures a lot about how cultures differ: a spectrum between “tight” and “loose,” referring to the extent to which social norms are automatically respected. Oregon is loose; Alabama is tight. Italy is loose; Singapore is tight. It’s a provocative thesis, back up by copious amounts of data, that could shed light on human behavior not only in different parts of the world, but in different settings at work or at school. The post- Liberation War generation of Bangladesh know stories from 1971 all too well. Our families are framed and bound by the history of this war. What Bangladeshi family has not been touched by the passion, famine, murders and blood that gave birth to a new nation as it seceded from Pakistan? Bangladesh was one of the only successful nationalist movements post-

The post- Liberation War generation of Bangladesh know stories from 1971 all too well. Our families are framed and bound by the history of this war. What Bangladeshi family has not been touched by the passion, famine, murders and blood that gave birth to a new nation as it seceded from Pakistan? Bangladesh was one of the only successful nationalist movements post-