Alexander Earl at The Marginalia Review of Books:

So what is to be done? What might seem like an esoteric crisis in Augustinian scholarship suddenly reflects a crisis about how we think, and how that thinking might give rise to a whole host of other predicaments. In which case, perhaps the resolution of one can aid us in resolving the other. In Augustine’s case, Kenyon argues that we should approach him in a holistic way and cease strip-mining his work for this or that argument or literary trope. We should especially not get bogged down in attempts to historically recreate Augustine’s psyche, but turn to the “overarching arguments and rhetorical strategy instead of individual passages” and “prefer interpretations that make sense of a text as a whole.” What we find, Kenyon avers, are “works centrally concerned with the practice of inquiry. When it comes to finding guidance, the dialogues look foremost to the act of inquiry itself: the fact that we can inquire at all tells us various things about ourselves.” The direction has shifted: what might it look like to view Augustine’s dialogues, and the nature of dialoguing in general, in terms of pedagogy and not in terms of content, as journeys of self-discovery instead of didactic treatises?

So what is to be done? What might seem like an esoteric crisis in Augustinian scholarship suddenly reflects a crisis about how we think, and how that thinking might give rise to a whole host of other predicaments. In which case, perhaps the resolution of one can aid us in resolving the other. In Augustine’s case, Kenyon argues that we should approach him in a holistic way and cease strip-mining his work for this or that argument or literary trope. We should especially not get bogged down in attempts to historically recreate Augustine’s psyche, but turn to the “overarching arguments and rhetorical strategy instead of individual passages” and “prefer interpretations that make sense of a text as a whole.” What we find, Kenyon avers, are “works centrally concerned with the practice of inquiry. When it comes to finding guidance, the dialogues look foremost to the act of inquiry itself: the fact that we can inquire at all tells us various things about ourselves.” The direction has shifted: what might it look like to view Augustine’s dialogues, and the nature of dialoguing in general, in terms of pedagogy and not in terms of content, as journeys of self-discovery instead of didactic treatises?

more here.

In the middle of the 1420s, a Dominican friar painted an altarpiece for his convent, San Domenico in Fiesole, Florence, showing the Christian story of the Annunciation. Fra Giovanni, now known as Fra Angelico, was a professional artist who had opted for monastic life largely for the freedom it gave him to paint. The altarpiece, recently restored by the Prado Museum, Madrid, where it has resided since the nineteenth century, hangs at the centre of an exhibition at the museum showing how Angelico took this freedom and created a new type of painting.

In the middle of the 1420s, a Dominican friar painted an altarpiece for his convent, San Domenico in Fiesole, Florence, showing the Christian story of the Annunciation. Fra Giovanni, now known as Fra Angelico, was a professional artist who had opted for monastic life largely for the freedom it gave him to paint. The altarpiece, recently restored by the Prado Museum, Madrid, where it has resided since the nineteenth century, hangs at the centre of an exhibition at the museum showing how Angelico took this freedom and created a new type of painting. On its glittering surface, America’s corporate economy appears to be in fantastic shape. The stock markets recently reached record highs, even if they dipped and bobbed after reaching those heights. Profits are soaring. Financing is cheap. The corporate tax rate has been cut. The unemployment rate is near a fifty-year low, with little inflation.

On its glittering surface, America’s corporate economy appears to be in fantastic shape. The stock markets recently reached record highs, even if they dipped and bobbed after reaching those heights. Profits are soaring. Financing is cheap. The corporate tax rate has been cut. The unemployment rate is near a fifty-year low, with little inflation. Bob Marra

Bob Marra

“I think I can safely say that nobody really understands quantum mechanics,” observed the physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman. That’s not surprising, as far as it goes. Science makes progress by confronting our lack of understanding, and quantum mechanics has a reputation for being especially mysterious.

“I think I can safely say that nobody really understands quantum mechanics,” observed the physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman. That’s not surprising, as far as it goes. Science makes progress by confronting our lack of understanding, and quantum mechanics has a reputation for being especially mysterious. The sleek blue-glass building of the Infosys corporation sits like an intruding spaceship amid the unpaved side streets and half-completed residential structures that surround it. Its giant porthole windows offer a peek into a Jetsons-esque world of workers gliding between floors on elevated moving sidewalks. For now, 19-year-old Nishank Nachappaa toils in the shadows of Infosys and the other high-tech companies that, like him, call the Electronic City section of Bangalore home. The high school graduate helps out at two dormitories for tech workers – one for young men, the other for young women – that his parents manage. His father maintains the buildings and his mother prepares meals for the 120 male and 30 female residents. Walk a block or two from the dorms and other corporate structures loom with multinational names such as Emerson and Yokogawa, Altametrics and Hewlett Packard.

The sleek blue-glass building of the Infosys corporation sits like an intruding spaceship amid the unpaved side streets and half-completed residential structures that surround it. Its giant porthole windows offer a peek into a Jetsons-esque world of workers gliding between floors on elevated moving sidewalks. For now, 19-year-old Nishank Nachappaa toils in the shadows of Infosys and the other high-tech companies that, like him, call the Electronic City section of Bangalore home. The high school graduate helps out at two dormitories for tech workers – one for young men, the other for young women – that his parents manage. His father maintains the buildings and his mother prepares meals for the 120 male and 30 female residents. Walk a block or two from the dorms and other corporate structures loom with multinational names such as Emerson and Yokogawa, Altametrics and Hewlett Packard.

Like many other nations, Canada is blessed with enormous resource wealth. We are the 7th largest oil-producing nation in the world (Norway is the 15th), with vast forests, mineral deposits and prime farming land. The Canadian province of Alberta legally controls almost 80 percent of the country’s fossil fuel production, has a similar population to Norway yet somehow managed to end up with a

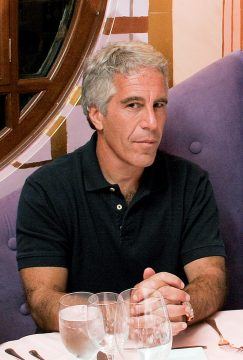

Like many other nations, Canada is blessed with enormous resource wealth. We are the 7th largest oil-producing nation in the world (Norway is the 15th), with vast forests, mineral deposits and prime farming land. The Canadian province of Alberta legally controls almost 80 percent of the country’s fossil fuel production, has a similar population to Norway yet somehow managed to end up with a  The M.I.T. Media Lab, which has been embroiled in a scandal over accepting donations from the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, had a deeper fund-raising relationship with Epstein than it has previously acknowledged, and it attempted to conceal the extent of its contacts with him. Dozens of pages of e-mails and other documents obtained by The New Yorker reveal that, although Epstein was listed as “disqualified” in M.I.T.’s official donor database, the Media Lab continued to accept gifts from him, consulted him about the use of the funds, and, by marking his contributions as anonymous, avoided disclosing their full extent, both publicly and within the university. Perhaps most notably, Epstein appeared to serve as an intermediary between the lab and other wealthy donors, soliciting millions of dollars in donations from individuals and organizations, including the technologist and philanthropist Bill Gates and the investor Leon Black. According to the records obtained by The New Yorker and accounts from current and former faculty and staff of the media lab, Epstein was credited with securing at least $7.5 million in donations for the lab, including two million dollars from Gates and $5.5 million from Black, gifts the e-mails describe as “directed” by Epstein or made at his behest. The effort to conceal the lab’s contact with Epstein was so widely known that some staff in the office of the lab’s director, Joi Ito, referred to Epstein as Voldemort or “he who must not be named.”

The M.I.T. Media Lab, which has been embroiled in a scandal over accepting donations from the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, had a deeper fund-raising relationship with Epstein than it has previously acknowledged, and it attempted to conceal the extent of its contacts with him. Dozens of pages of e-mails and other documents obtained by The New Yorker reveal that, although Epstein was listed as “disqualified” in M.I.T.’s official donor database, the Media Lab continued to accept gifts from him, consulted him about the use of the funds, and, by marking his contributions as anonymous, avoided disclosing their full extent, both publicly and within the university. Perhaps most notably, Epstein appeared to serve as an intermediary between the lab and other wealthy donors, soliciting millions of dollars in donations from individuals and organizations, including the technologist and philanthropist Bill Gates and the investor Leon Black. According to the records obtained by The New Yorker and accounts from current and former faculty and staff of the media lab, Epstein was credited with securing at least $7.5 million in donations for the lab, including two million dollars from Gates and $5.5 million from Black, gifts the e-mails describe as “directed” by Epstein or made at his behest. The effort to conceal the lab’s contact with Epstein was so widely known that some staff in the office of the lab’s director, Joi Ito, referred to Epstein as Voldemort or “he who must not be named.” AS A MEDICAL STUDENT

AS A MEDICAL STUDENT

Ted Mann in Tablet:

Ted Mann in Tablet: Elizabeth Chatterjee in the LRB:

Elizabeth Chatterjee in the LRB: Clive Cookson in the FT:

Clive Cookson in the FT: In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.

In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.