Maureen Johnson in Crime Reads:

It’s happened. You’ve finally taken that dream trip to England. You have seen Big Ben, Buckingham Palace, and Hyde Park. You rode in a London cab and walked all over the Tower of London. Now you’ve decided to leave the hustle and bustle of the city and stretch your legs in the verdant countryside of these green and pleasant lands. You’ve seen all the shows. You know what to expect. You’ll drink a pint in the sunny courtyard of a local pub. You’ll wander down charming alleyways between stone cottages. Residents will tip their flat caps at you as they bicycle along cobblestone streets. It will be idyllic.

It’s happened. You’ve finally taken that dream trip to England. You have seen Big Ben, Buckingham Palace, and Hyde Park. You rode in a London cab and walked all over the Tower of London. Now you’ve decided to leave the hustle and bustle of the city and stretch your legs in the verdant countryside of these green and pleasant lands. You’ve seen all the shows. You know what to expect. You’ll drink a pint in the sunny courtyard of a local pub. You’ll wander down charming alleyways between stone cottages. Residents will tip their flat caps at you as they bicycle along cobblestone streets. It will be idyllic.

Unless you end up in an English Murder Village. It’s easy enough to do. You may not know you are in a Murder Village, as they look like all other villages. So when you visit Womble Hollow or Shrimpling or Pickles-in-the-Woods or Nasty Bottom or Wombat-on-Sea or wherever you are going, you must have a plan. Below is a list of sensible precautions you can take on any trip to an English village. Follow them and you may just live.

More here.

January 27th marks the 10th anniversary of the death of the great historian and activist

January 27th marks the 10th anniversary of the death of the great historian and activist  Art historian Jean M. Evans (the current Chief Curator and Deputy Director of the Oriental Institute) writes in The Lives of Sumerian Sculpture: An Archeology of the Early Dynastic Temple that the “eerie effect of the enlarged eyes… has often arisen as a question. These eyes are perplexing.” Several hypotheses have been tendered over the decades as to why the Tal Asmar figurines, and other Sumerian votive statues, have this distinctive characteristic. Wide eyes, especially those absurdly large ones on these idols, could convey an emotion of surprise, or of ecstasy, or pupil-engorged intoxication. Evans gives several examples of modern interactions viewers have had with the figurines, quoting the American painter Willem de Kooning who commented that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had a cache of Sumerian statues with “huge staring goggle eyes” that were “wild-eyed,” and the psychologist George Frankl writing in The Social History of the Unconsciousness that these spheres of obsidian and opal convey a “sense of awe and apprehension which obviously indicated the anxiety those people felt in the presence of the gods.” Regardless of the intent (or multiple purposes) of the statues’ creators, Evans makes the point that the artworks have become “the subjects and objects of gaze.” Consider the first of these functions when deciding why the creatures’ pupils are so wide–it’s because they’re looking at you.

Art historian Jean M. Evans (the current Chief Curator and Deputy Director of the Oriental Institute) writes in The Lives of Sumerian Sculpture: An Archeology of the Early Dynastic Temple that the “eerie effect of the enlarged eyes… has often arisen as a question. These eyes are perplexing.” Several hypotheses have been tendered over the decades as to why the Tal Asmar figurines, and other Sumerian votive statues, have this distinctive characteristic. Wide eyes, especially those absurdly large ones on these idols, could convey an emotion of surprise, or of ecstasy, or pupil-engorged intoxication. Evans gives several examples of modern interactions viewers have had with the figurines, quoting the American painter Willem de Kooning who commented that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had a cache of Sumerian statues with “huge staring goggle eyes” that were “wild-eyed,” and the psychologist George Frankl writing in The Social History of the Unconsciousness that these spheres of obsidian and opal convey a “sense of awe and apprehension which obviously indicated the anxiety those people felt in the presence of the gods.” Regardless of the intent (or multiple purposes) of the statues’ creators, Evans makes the point that the artworks have become “the subjects and objects of gaze.” Consider the first of these functions when deciding why the creatures’ pupils are so wide–it’s because they’re looking at you. Through the language of his ‘troubling strangeness’,

Through the language of his ‘troubling strangeness’, AMONG THOSE L.A. RESIDENTS who have listened (patiently) over the years to KPFK-FM, our local — and at times volatile — Pacifica-based radio station, many will recall my erstwhile colleague at the station Jacki Apple and her excellent performance art program, Soundings, which ran from 1982 to 1995. Since that was an era long before the crucial turning point of 2012–’13, when humanity finally reached its potential as walking appendages of electronic devices (a development actually prophesied by some of those performance artists), Jacki was an essential, one-woman dervish of activity in this city, a writer-observer who avidly promoted the furthest fringes of performance art and experimental music in the Southland, through both the printed word (in the pages of High Performance and Artweek) and that unlikely 20th-century medium of radio.

AMONG THOSE L.A. RESIDENTS who have listened (patiently) over the years to KPFK-FM, our local — and at times volatile — Pacifica-based radio station, many will recall my erstwhile colleague at the station Jacki Apple and her excellent performance art program, Soundings, which ran from 1982 to 1995. Since that was an era long before the crucial turning point of 2012–’13, when humanity finally reached its potential as walking appendages of electronic devices (a development actually prophesied by some of those performance artists), Jacki was an essential, one-woman dervish of activity in this city, a writer-observer who avidly promoted the furthest fringes of performance art and experimental music in the Southland, through both the printed word (in the pages of High Performance and Artweek) and that unlikely 20th-century medium of radio. Forty thousand years ago in Europe, we were not the only human species alive – there were

Forty thousand years ago in Europe, we were not the only human species alive – there were  In her just-published “

In her just-published “ The scientific work that I do on the brain basis of consciousness is sometimes misunderstood – a misunderstanding which I think comes mainly from the political divide between mystics and materialists. I am a materialist, and reactions to my work tend to follow along the lines of: ‘keep your scientific hands off my consciousness mystery’.

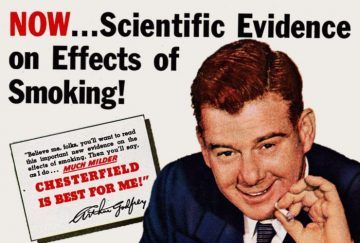

The scientific work that I do on the brain basis of consciousness is sometimes misunderstood – a misunderstanding which I think comes mainly from the political divide between mystics and materialists. I am a materialist, and reactions to my work tend to follow along the lines of: ‘keep your scientific hands off my consciousness mystery’. Decision makers atop today’s corporate structures are responsible for delivering short- and long-term financial returns, and in the pursuit of these goals they place profits and growth above all else. Avoidance of financial loss, to many corporate executives, is an alibi for just about any ugly decision. This is not to say that decisions at the highest level are black-and-white or simple; they are dictated by factors such as the cost of possible government regulation and potential loss of market share to less hazardous products. And, of course, companies are afraid of being sued by people sickened by their products, which costs money and can result in serious damage to the brand. All of this is part of the corporate calculus.

Decision makers atop today’s corporate structures are responsible for delivering short- and long-term financial returns, and in the pursuit of these goals they place profits and growth above all else. Avoidance of financial loss, to many corporate executives, is an alibi for just about any ugly decision. This is not to say that decisions at the highest level are black-and-white or simple; they are dictated by factors such as the cost of possible government regulation and potential loss of market share to less hazardous products. And, of course, companies are afraid of being sued by people sickened by their products, which costs money and can result in serious damage to the brand. All of this is part of the corporate calculus. My experience at the Auschwitz exhibit was a powerful one. But it was actually a familiar one. We are used to experiencing the horror of the Holocaust through the lens of Auschwitz. When we talk about the six million, we picture concentration camps, ghettos, cattle cars.

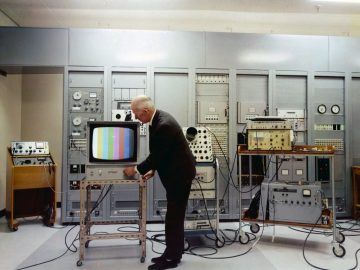

My experience at the Auschwitz exhibit was a powerful one. But it was actually a familiar one. We are used to experiencing the horror of the Holocaust through the lens of Auschwitz. When we talk about the six million, we picture concentration camps, ghettos, cattle cars. How much our historical context informs our perceptions of and beliefs about color is ably illustrated by Susan Murray’s award-winning book Bright Signals. Tracing the evolution of color television in America from the late 1920s to the early 1970s, the book successfully demonstrates how the medium reflected and refracted American social and political history, despite its initially halting, tentative development. Industry leaders, Murray shows, only progressively overcame regulators’, advertisers’, and the public’s initial resistance to color television as a finicky luxury.

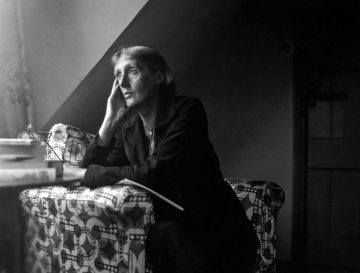

How much our historical context informs our perceptions of and beliefs about color is ably illustrated by Susan Murray’s award-winning book Bright Signals. Tracing the evolution of color television in America from the late 1920s to the early 1970s, the book successfully demonstrates how the medium reflected and refracted American social and political history, despite its initially halting, tentative development. Industry leaders, Murray shows, only progressively overcame regulators’, advertisers’, and the public’s initial resistance to color television as a finicky luxury. What moves you to stand in the presence of the house, the landscape, the objects of a writer whom you so admire? Why are literary pilgrimages so compelling?

What moves you to stand in the presence of the house, the landscape, the objects of a writer whom you so admire? Why are literary pilgrimages so compelling?  Just off the coast of Espírito Santo, an island in the Vanuatu archipelago of the South Western Pacific, there is a massive underwater dump. Called Million Dollar Point after the millions of dollars worth of material disposed there, the dump is a popular diving destination, and divers report an amazing quantity of wreckage: jeeps, six-wheel drive trucks, bulldozers, semi-trailers, fork lifts, tractors, bound sheets of corrugated iron, unopened boxes of clothing, and cases of Coca-Cola. The dumped goods were not abandoned by the ni-Vanuatu people, nor by the Franco-British Condominium who ruled Vanuatu (then known as the New Hebrides) from 1906 until 1980, but by personnel of a WWII American military base named Buttons. At the end of the war, sometime between August 1945 and December 1947, the US military interred supplies, equipment, and vehicles under water.

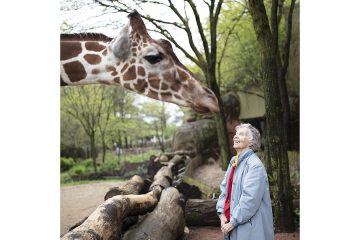

Just off the coast of Espírito Santo, an island in the Vanuatu archipelago of the South Western Pacific, there is a massive underwater dump. Called Million Dollar Point after the millions of dollars worth of material disposed there, the dump is a popular diving destination, and divers report an amazing quantity of wreckage: jeeps, six-wheel drive trucks, bulldozers, semi-trailers, fork lifts, tractors, bound sheets of corrugated iron, unopened boxes of clothing, and cases of Coca-Cola. The dumped goods were not abandoned by the ni-Vanuatu people, nor by the Franco-British Condominium who ruled Vanuatu (then known as the New Hebrides) from 1906 until 1980, but by personnel of a WWII American military base named Buttons. At the end of the war, sometime between August 1945 and December 1947, the US military interred supplies, equipment, and vehicles under water. When Canadian biologist Anne Innis Dagg was 3 years old, her mother took her to the zoo for the first time. There she saw her first giraffe, and a lifelong love affair ensued. And who can blame her? Is there any other four-legged creature whose looks are more magisterially goofy? Dagg is the focus of Alison Reid’s “The Woman Who Loves Giraffes,” and it confirms a long-held tenet of mine: If the subject of a documentary is fascinating, it doesn’t much matter if the filmmaking is workmanlike. Now in her 80s, Dagg is such a singular personality that everything about her seems sprightly and newly minted.

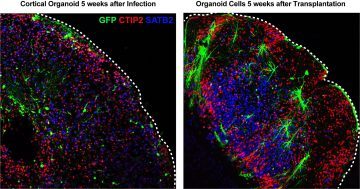

When Canadian biologist Anne Innis Dagg was 3 years old, her mother took her to the zoo for the first time. There she saw her first giraffe, and a lifelong love affair ensued. And who can blame her? Is there any other four-legged creature whose looks are more magisterially goofy? Dagg is the focus of Alison Reid’s “The Woman Who Loves Giraffes,” and it confirms a long-held tenet of mine: If the subject of a documentary is fascinating, it doesn’t much matter if the filmmaking is workmanlike. Now in her 80s, Dagg is such a singular personality that everything about her seems sprightly and newly minted. Brain organoids—three-dimensional balls of brain-like tissue grown in the lab, often from human stem cells—have been touted for their potential to let scientists study the formation of the brain’s complex circuitry in controlled laboratory conditions. The discussion surrounding brain organoids has been effusive, with some scientists suggesting they will make it possible to rapidly develop treatments for devastating brain diseases and others warning that organoids may soon attain some form of consciousness. But a new UC San Francisco study offers a more restrained perspective, by showing that widely used

Brain organoids—three-dimensional balls of brain-like tissue grown in the lab, often from human stem cells—have been touted for their potential to let scientists study the formation of the brain’s complex circuitry in controlled laboratory conditions. The discussion surrounding brain organoids has been effusive, with some scientists suggesting they will make it possible to rapidly develop treatments for devastating brain diseases and others warning that organoids may soon attain some form of consciousness. But a new UC San Francisco study offers a more restrained perspective, by showing that widely used