Jocelyn Kaiser in Science:

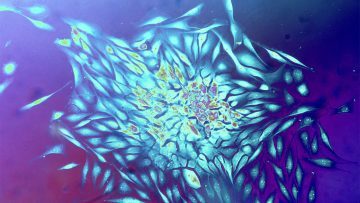

The largest ever study to analyze entire tumor genomes has provided the most complete picture yet of how DNA glitches drive tumor cell growth. Researchers say the results, released today in six papers in Nature and 17 in other journals, could pave the way for full genome sequencing of all patients’ tumors. Such sequences could then be used in efforts to match each patient to a molecular treatment. The Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) project, which had a cast of more than 1300 scientists and clinicians around the world, analyzed 2658 whole genomes for 38 types of cancer, from breast to liver. “What stands out from these studies is the rigor of doing this in a systemic way,” says cancer geneticist Marcin Cieslik, who with colleague Arul Chinnaiyan at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, co-authored a commentary on the papers. Previous published studies—such as those from the U.S.-funded Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)—originally looked only at the “exome,” protein-coding DNA that make up just 1% of the genome, of tumors because it was cheaper and easier. But this shortcut left out many changes that might drive cancer growth. With DNA sequencing costs falling, the TCGA and the International Cancer Genome Consortium turned to the entire genome about 10 years ago, sequencing all 3 billion DNA base pairs, including regulatory regions within noncoding DNA, for many tumor samples. These groups also looked for large rearrangements and other structural changes that exome sequencing misses.

The PCAWG study’s 1300-strong team then dug into the data, which the other groups had made freely available in databases. Its analysis didn’t find many new so-called “driver” mutations within genes or noncoding DNA that power cell growth in tumors. But the researchers found “many more ways … to change those pathways” of cancer growth, said project member Lincoln Stein of the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research during a press call. For example, about one-fifth of the tumors had cells in which chromosomes shattered and rearranged, a bizarre phenomenon known as chromothripsis. Each tumor had four to five driver mutations on average. In all, the PCAWG project was able to find at least one driver mutation in about 95% of the tumor samples, compared with just 67% with exome sequencing, says Peter Campbell of the Wellcome Sanger Institute, another project member. This means many more cancer patients can in principle now be matched to a drug that targets the protein made by that driver gene. One PCAWG team also figured out how to trace the evolution of the mutations in a single tumor biopsy. The group confirmed that the initial mutations often cropped up years or decades before the cancers were diagnosed, suggesting many could be detected and treated much earlier.

More here.

The

The  The

The  As we enter what feels like the second or third decade of the 2020 presidential campaign, a question hovers menacingly over American politics: Can liberals get a grip? Three years into the Trump era, it cannot have escaped anyone that the country’s political system is in the throes of a major crisis. Yet the mainstream of the Democratic Party remains bogged down, lurching back and forth between melancholy and hysteria. “The Republic is in danger!” the Rachel Maddows of the world intone, but aside from a Trump impeachment that has no hope of actually removing him from office, the solutions on offer stay the same as they were three, ten, fifteen years ago: means-tested tweaks to what little remains of the welfare state, limp appeals to civility and tolerance for (meaning accommodation to) opposing political views, and a “muscular” but gloomy foreign policy that envisions our forever wars stretching on for decades. For more than half a century, the political program that is now called American liberal centrism remade much of the world in its own image and turned the US into the preeminent military and economic power. Today, centrists’ best idea for a bold, young candidate is a millennial Harvard robot who worked for the odious consulting firm McKinsey before, as a midwestern mayor, apparently alienating every single black resident of South Bend. This is an ideology suffering from a failure of imagination.

As we enter what feels like the second or third decade of the 2020 presidential campaign, a question hovers menacingly over American politics: Can liberals get a grip? Three years into the Trump era, it cannot have escaped anyone that the country’s political system is in the throes of a major crisis. Yet the mainstream of the Democratic Party remains bogged down, lurching back and forth between melancholy and hysteria. “The Republic is in danger!” the Rachel Maddows of the world intone, but aside from a Trump impeachment that has no hope of actually removing him from office, the solutions on offer stay the same as they were three, ten, fifteen years ago: means-tested tweaks to what little remains of the welfare state, limp appeals to civility and tolerance for (meaning accommodation to) opposing political views, and a “muscular” but gloomy foreign policy that envisions our forever wars stretching on for decades. For more than half a century, the political program that is now called American liberal centrism remade much of the world in its own image and turned the US into the preeminent military and economic power. Today, centrists’ best idea for a bold, young candidate is a millennial Harvard robot who worked for the odious consulting firm McKinsey before, as a midwestern mayor, apparently alienating every single black resident of South Bend. This is an ideology suffering from a failure of imagination. Reichert’s body of work is characterized by consistent themes across fifty years of nonstop production. They are films about the lives of ordinary working people in America, often women, usually set in the Midwest. The films are grounded in deep research and driven by a commitment to social justice. They methodically explore a situation or issue, with close, respectful observation and interviews that are always conducted by Reichert herself. These films were often designed within a context of social movements and intended to have demonstrable effects in the world.

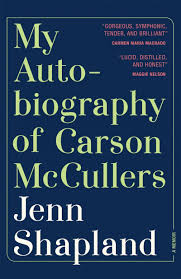

Reichert’s body of work is characterized by consistent themes across fifty years of nonstop production. They are films about the lives of ordinary working people in America, often women, usually set in the Midwest. The films are grounded in deep research and driven by a commitment to social justice. They methodically explore a situation or issue, with close, respectful observation and interviews that are always conducted by Reichert herself. These films were often designed within a context of social movements and intended to have demonstrable effects in the world. I struggle with biography as a genre, because I’m deeply interested in life writing, but allergic to anything that starts with “So-and-so was born in 1946.” Who is this third person claiming omniscience about someone else’s life? Why must we begin with birth, which no one remembers, or with ancestors, and move chronologically? The written record about Carson tries to sandwich her into a conventional, straight biography, wherein a person is born, comes of age, marries, and dies. That’s just not how her life went, or that’s not a way to capture the really exciting stuff, like her relationships with women that happened while she was married, her getting divorced and remarrying and abandoning the same guy, living with the queer cadre at February House, meeting Mary Mercer in her forties and falling in love, coming of age late in life. Queer narratives are all over the place, and queer people frequently take a long time to figure shit out. They live many lives in the space of one life, often with different identities, genders, pronouns, bodies, and styles. Queer narratives demand new forms, and I would love to see more queer writing that fucks with all different genres and literary conventions.

I struggle with biography as a genre, because I’m deeply interested in life writing, but allergic to anything that starts with “So-and-so was born in 1946.” Who is this third person claiming omniscience about someone else’s life? Why must we begin with birth, which no one remembers, or with ancestors, and move chronologically? The written record about Carson tries to sandwich her into a conventional, straight biography, wherein a person is born, comes of age, marries, and dies. That’s just not how her life went, or that’s not a way to capture the really exciting stuff, like her relationships with women that happened while she was married, her getting divorced and remarrying and abandoning the same guy, living with the queer cadre at February House, meeting Mary Mercer in her forties and falling in love, coming of age late in life. Queer narratives are all over the place, and queer people frequently take a long time to figure shit out. They live many lives in the space of one life, often with different identities, genders, pronouns, bodies, and styles. Queer narratives demand new forms, and I would love to see more queer writing that fucks with all different genres and literary conventions. In the 1980s, the Guardian newspaper in Lagos published a weekly Literary Series, including full-length essays on notable writers as well as poems, stories and short reviews. Those essays were later collected into the two-volume Perspectives on Nigerian Literature, edited by Yemi Ogunbiyi. Of the 53 essays in the second volume, Teju wrote eight, the most contributions by a single person in that volume.

In the 1980s, the Guardian newspaper in Lagos published a weekly Literary Series, including full-length essays on notable writers as well as poems, stories and short reviews. Those essays were later collected into the two-volume Perspectives on Nigerian Literature, edited by Yemi Ogunbiyi. Of the 53 essays in the second volume, Teju wrote eight, the most contributions by a single person in that volume.

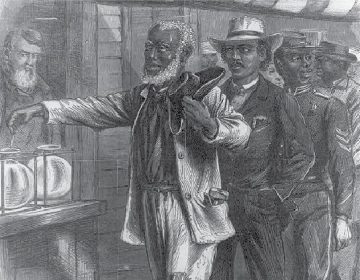

The Voting Rights Act is a historic civil rights law that is meant to ensure that the right to vote is not denied on account of race or color.

The Voting Rights Act is a historic civil rights law that is meant to ensure that the right to vote is not denied on account of race or color. As a technology entrepreneur, when I am approached by startup founders for fundraising advice, I ask: “What would the world look like if you got everything you’re asking for?” It’s a test to see whether they are setting out to solve the right problem or whether they are choosing their preferred course of action and justifying retrospectively.

As a technology entrepreneur, when I am approached by startup founders for fundraising advice, I ask: “What would the world look like if you got everything you’re asking for?” It’s a test to see whether they are setting out to solve the right problem or whether they are choosing their preferred course of action and justifying retrospectively. It’s done. A triumph of dogged negotiation by May then, briefly, Johnson, has fulfilled the most pointless, masochistic ambition ever dreamed of in the history of these islands. The rest of the world, presidents Putin and Trump excepted, have watched on in astonishment and dismay. A majority voted in December for parties which supported a second referendum. But those parties failed lamentably to make common cause. We must pack up our tents, perhaps to the sound of church bells, and hope to begin the 15-year trudge, back towards some semblance of where we were yesterday with our multiple trade deals, security, health and scientific co-operation and a thousand other useful arrangements.

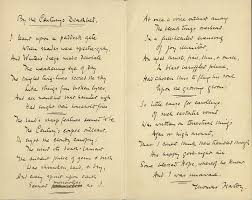

It’s done. A triumph of dogged negotiation by May then, briefly, Johnson, has fulfilled the most pointless, masochistic ambition ever dreamed of in the history of these islands. The rest of the world, presidents Putin and Trump excepted, have watched on in astonishment and dismay. A majority voted in December for parties which supported a second referendum. But those parties failed lamentably to make common cause. We must pack up our tents, perhaps to the sound of church bells, and hope to begin the 15-year trudge, back towards some semblance of where we were yesterday with our multiple trade deals, security, health and scientific co-operation and a thousand other useful arrangements. The integrating power of the erotics of poetry was on Heaney’s mind when he decided to take on the task of producing a modern English version of the quintessentially Anglo-Saxon Beowulf. Contemplating a version distinguished by many Hiberno-English uses, Heaney concluded, as he wrote in “The Irish Poet and Britain”, ‘So, so be it. Let Beowulf now be a book from Ireland.’

The integrating power of the erotics of poetry was on Heaney’s mind when he decided to take on the task of producing a modern English version of the quintessentially Anglo-Saxon Beowulf. Contemplating a version distinguished by many Hiberno-English uses, Heaney concluded, as he wrote in “The Irish Poet and Britain”, ‘So, so be it. Let Beowulf now be a book from Ireland.’ In 1944, in Warsaw, German soldiers scrawled numbers on the buildings in white paint and then systematically demolished the city, while the Soviet army watched and waited across the Vistula. After the war, the Poles returned to Warsaw and, living in the rubble, began to rebuild. Devastated cities across Europe faced the same choices. Should the ruins be left in view, like the cathedral at Coventry, with new buildings erected beside them, a permanent memorial? Should the rubble (with its dead) be hidden and a new, modern city built on top of it? Or perhaps, as the Poles decided, the old city should be replicated, rebuilt in the same place, in every last detail—every cornice, lamppost, and windowsill—an act of defiance and despair, the fiercest response to the fact that we can’t bring back the past, we can’t bring back the dead. In this replication was a kind of terror—the calling forth of spirits and the speaking aloud of a harrowing, unanswerable doubt: that the replica might erase precisely what it was meant to memorialize.

In 1944, in Warsaw, German soldiers scrawled numbers on the buildings in white paint and then systematically demolished the city, while the Soviet army watched and waited across the Vistula. After the war, the Poles returned to Warsaw and, living in the rubble, began to rebuild. Devastated cities across Europe faced the same choices. Should the ruins be left in view, like the cathedral at Coventry, with new buildings erected beside them, a permanent memorial? Should the rubble (with its dead) be hidden and a new, modern city built on top of it? Or perhaps, as the Poles decided, the old city should be replicated, rebuilt in the same place, in every last detail—every cornice, lamppost, and windowsill—an act of defiance and despair, the fiercest response to the fact that we can’t bring back the past, we can’t bring back the dead. In this replication was a kind of terror—the calling forth of spirits and the speaking aloud of a harrowing, unanswerable doubt: that the replica might erase precisely what it was meant to memorialize. ‘Sometimes I think I am the enemy of womankind,’ Lowell told Hardwick. He hurt all three of his wives grievously, but he believed in their greatness as writers, enriched them creatively and improved their sense of self-worth. He gave the first, Jean Stafford, lifelong facial disfigurement after crashing the car they were in while drunk at the wheel, and later broke her nose during a drunken row in New Orleans. He also encouraged her during the writing of her first novel, Boston Adventure, which sold over 400,000 copies following its publication in 1944. The novel that Hardwick wrote after marrying Lowell, The Simple Truth, is a big improvement on its predecessor, and the novel she wrote as a response to The Dolphin after his death, Sleepless Nights, is her best. ‘Everything I know’, she attested, ‘I learned from him.’

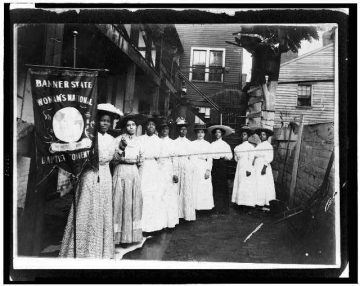

‘Sometimes I think I am the enemy of womankind,’ Lowell told Hardwick. He hurt all three of his wives grievously, but he believed in their greatness as writers, enriched them creatively and improved their sense of self-worth. He gave the first, Jean Stafford, lifelong facial disfigurement after crashing the car they were in while drunk at the wheel, and later broke her nose during a drunken row in New Orleans. He also encouraged her during the writing of her first novel, Boston Adventure, which sold over 400,000 copies following its publication in 1944. The novel that Hardwick wrote after marrying Lowell, The Simple Truth, is a big improvement on its predecessor, and the novel she wrote as a response to The Dolphin after his death, Sleepless Nights, is her best. ‘Everything I know’, she attested, ‘I learned from him.’ During the 19th and 20th centuries, Black women played an active role in the struggle for universal suffrage. They participated in political meetings and organized political societies. African American women attended political conventions at their local churches where they planned strategies to gain the right to vote. In the late 1800s, more Black women worked for churches, newspapers, secondary schools, and colleges, which gave them a larger platform to promote their ideas.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Black women played an active role in the struggle for universal suffrage. They participated in political meetings and organized political societies. African American women attended political conventions at their local churches where they planned strategies to gain the right to vote. In the late 1800s, more Black women worked for churches, newspapers, secondary schools, and colleges, which gave them a larger platform to promote their ideas. THE ERASURE OF the Palestinians on display this week as President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu unveiled a one-sided “

THE ERASURE OF the Palestinians on display this week as President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu unveiled a one-sided “ While some details of the mechanisms of splicing remain to be worked out, it’s known that mature, edited mRNAs result from an interplay between multiple factors within and outside the transcript itself. Among these is the spliceosome, the machinery that carries out the splicing. Each splicing event requires three components: the splice donor, a GU nucleotide sequence at one end of the intron; a splice acceptor, an AG nucleotide sequence at the opposite end; and a branch point, an A approximately 20–40 nucleotides away from the splice acceptor. These three “splice sites” are recognized by two core small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) of the spliceosome, U1 and U2, followed by a protein, U2AF. The binding of these molecules to a transcript recruits a complex of three more snRNAs—U4, U5, and U6—which facilitates the splicing reaction. A variety of factors affect how transcripts from a particular gene are spliced. Exon recognition by the spliceosome can be influenced by RNA binding proteins (RBPs), which bind to enhancer and silencer motifs within the mRNA and help or hinder spliceosome recognition of the splice sites. And because pre-mRNAs are frequently spliced as they’re transcribed, the speed of transcription by RNA polymerase II further tunes the window of opportunity for splice site recognition by the spliceosome.

While some details of the mechanisms of splicing remain to be worked out, it’s known that mature, edited mRNAs result from an interplay between multiple factors within and outside the transcript itself. Among these is the spliceosome, the machinery that carries out the splicing. Each splicing event requires three components: the splice donor, a GU nucleotide sequence at one end of the intron; a splice acceptor, an AG nucleotide sequence at the opposite end; and a branch point, an A approximately 20–40 nucleotides away from the splice acceptor. These three “splice sites” are recognized by two core small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) of the spliceosome, U1 and U2, followed by a protein, U2AF. The binding of these molecules to a transcript recruits a complex of three more snRNAs—U4, U5, and U6—which facilitates the splicing reaction. A variety of factors affect how transcripts from a particular gene are spliced. Exon recognition by the spliceosome can be influenced by RNA binding proteins (RBPs), which bind to enhancer and silencer motifs within the mRNA and help or hinder spliceosome recognition of the splice sites. And because pre-mRNAs are frequently spliced as they’re transcribed, the speed of transcription by RNA polymerase II further tunes the window of opportunity for splice site recognition by the spliceosome.