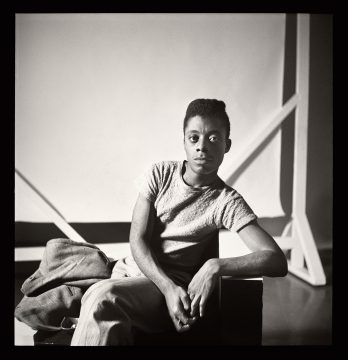

James Baldwin in The New Yorker:

I was icily determined—more determined, really, than I then knew—never to make my peace with the ghetto but to die and go to Hell before I would let any white man spit on me, before I would accept my “place” in this republic. I did not intend to allow the white people of this country to tell me who I was, and limit me that way, and polish me off that way. And yet, of course, at the same time, I was being spat on and defined and described and limited, and could have been polished off with no effort whatever. Every Negro boy—in my situation during those years, at least—who reaches this point realizes, at once, profoundly, because he wants to live, that he stands in great peril and must find, with speed, a “thing,” a gimmick, to lift him out, to start him on his way. And it does not matter what the gimmick is.

I was icily determined—more determined, really, than I then knew—never to make my peace with the ghetto but to die and go to Hell before I would let any white man spit on me, before I would accept my “place” in this republic. I did not intend to allow the white people of this country to tell me who I was, and limit me that way, and polish me off that way. And yet, of course, at the same time, I was being spat on and defined and described and limited, and could have been polished off with no effort whatever. Every Negro boy—in my situation during those years, at least—who reaches this point realizes, at once, profoundly, because he wants to live, that he stands in great peril and must find, with speed, a “thing,” a gimmick, to lift him out, to start him on his way. And it does not matter what the gimmick is.

…Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death—ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will honor The Black History Month. This year’s theme is “African Americans and the Vote.” Readers are encouraged to send in their suggestions)

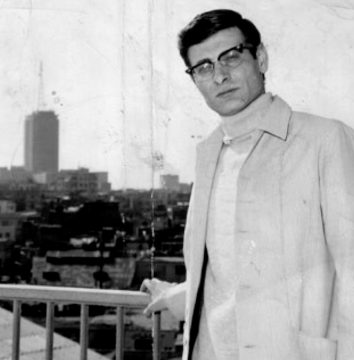

The late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (1941–2008) liked to write in the mornings, preferably in a narrow room with a window overlooking a tree. He required solitude and coffee; he wrote in black ink on loose, thick, white paper. He often listened to music. His poems, he told the journalist and fellow poet Abbas Beydoun in 1995, always started out as a cadence, a tempo. “My mornings are sad,” Darwish said. But his afternoons and evenings could be joyful, for as he explained to Beydoun:

The late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (1941–2008) liked to write in the mornings, preferably in a narrow room with a window overlooking a tree. He required solitude and coffee; he wrote in black ink on loose, thick, white paper. He often listened to music. His poems, he told the journalist and fellow poet Abbas Beydoun in 1995, always started out as a cadence, a tempo. “My mornings are sad,” Darwish said. But his afternoons and evenings could be joyful, for as he explained to Beydoun: Picture a calm river. Now picture a torrent of white water. What is the difference between the two? To mathematicians and physicists it’s this: The smooth river flows in one direction, while the torrent flows in many different directions at once.

Picture a calm river. Now picture a torrent of white water. What is the difference between the two? To mathematicians and physicists it’s this: The smooth river flows in one direction, while the torrent flows in many different directions at once. What if everything you think you know about politics is wrong? What if there aren’t really American swing voters—or not enough, anyway, to pick the next president? What if it doesn’t matter much who the Democratic nominee is? What if there is no such thing as “the center,” and the party in power can govern however it wants for two years, because the results of that first midterm are going to be bad regardless? What if the Democrats’ big 41-seat midterm victory in 2018 didn’t happen because candidates focused on health care and kitchen-table issues, but simply because they were running against the party in the White House? What if the outcome in 2020 is pretty much foreordained, too?

What if everything you think you know about politics is wrong? What if there aren’t really American swing voters—or not enough, anyway, to pick the next president? What if it doesn’t matter much who the Democratic nominee is? What if there is no such thing as “the center,” and the party in power can govern however it wants for two years, because the results of that first midterm are going to be bad regardless? What if the Democrats’ big 41-seat midterm victory in 2018 didn’t happen because candidates focused on health care and kitchen-table issues, but simply because they were running against the party in the White House? What if the outcome in 2020 is pretty much foreordained, too? The Cuban-born Ms. Sánchez, who will turn 94 this summer, has spent some 50 years making abstract, shaped, sculptural paintings, and is still at work. While modern art has a firmly established tradition of objects that simultaneously hang on the wall and jut into space (think of Robert Rauschenberg’s collagelike “

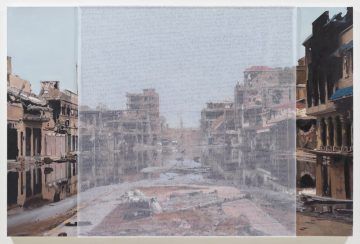

The Cuban-born Ms. Sánchez, who will turn 94 this summer, has spent some 50 years making abstract, shaped, sculptural paintings, and is still at work. While modern art has a firmly established tradition of objects that simultaneously hang on the wall and jut into space (think of Robert Rauschenberg’s collagelike “ Aesthetically the artworks are strangely, hauntingly beautiful. They spark a desire to sojourn a while with the images, sensing that each one offers something that is difficult to refuse, difficult to ignore. In this regard, the collection of works compel the viewer to experience their testimony. Without this aesthetic intervention, the paintings might lack force and simply read as interesting comments on a political moment. Instead, it is an evocation of a sense of vulnerability and beauty that is the enlivening force in this body of work.

Aesthetically the artworks are strangely, hauntingly beautiful. They spark a desire to sojourn a while with the images, sensing that each one offers something that is difficult to refuse, difficult to ignore. In this regard, the collection of works compel the viewer to experience their testimony. Without this aesthetic intervention, the paintings might lack force and simply read as interesting comments on a political moment. Instead, it is an evocation of a sense of vulnerability and beauty that is the enlivening force in this body of work. And yet there were probably also ways in which the characters we created revealed something about us. I liked outsiders of various kinds, half-orcs and thieves, sympathetic fringe types; partly, no doubt, because I never stayed anywhere long enough in my childhood to be an insider. For some reason, I also preferred shorter races, halflings and dwarves, and identified with the Bilbos and Gimlis of the world rather than the Aragorns and Boromirs – the tall, powerful men – although I was six foot six (and a deeply frustrated benchwarmer on the basketball team) by the time I finished high school. D&D grew out of Middle Earth and drew on William Morris-style fantasies of medievalism. I read Morris, too (The Defence of Guenevere), and like any good American loved the Cotswolds (which we day-tripped into during our Oxford years). The charm of the English countryside suggests a life in which you can walk out of one small world, through fields, hills and countryside, to enter another, and this is also the romance of Dungeons & Dragons.

And yet there were probably also ways in which the characters we created revealed something about us. I liked outsiders of various kinds, half-orcs and thieves, sympathetic fringe types; partly, no doubt, because I never stayed anywhere long enough in my childhood to be an insider. For some reason, I also preferred shorter races, halflings and dwarves, and identified with the Bilbos and Gimlis of the world rather than the Aragorns and Boromirs – the tall, powerful men – although I was six foot six (and a deeply frustrated benchwarmer on the basketball team) by the time I finished high school. D&D grew out of Middle Earth and drew on William Morris-style fantasies of medievalism. I read Morris, too (The Defence of Guenevere), and like any good American loved the Cotswolds (which we day-tripped into during our Oxford years). The charm of the English countryside suggests a life in which you can walk out of one small world, through fields, hills and countryside, to enter another, and this is also the romance of Dungeons & Dragons. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, aimed to overcome legal barriers at the state and local levels that prevented African Americans from exercising their right to vote as guaranteed under the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Voting Rights Act is considered one of the most far-reaching pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, aimed to overcome legal barriers at the state and local levels that prevented African Americans from exercising their right to vote as guaranteed under the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Voting Rights Act is considered one of the most far-reaching pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history. Researchers at the University of Washington have discovered a novel DNA-sensing pathway that launches an antiviral response to foreign genetic material in human cells. Triggered by an enzyme called DNA protein kinase (DNA-PK), the newly found pathway is independent of the cGAS-STING pathway—until now considered the main regulator of mammalian innate immune responses to DNA—and is missing or inactive in mouse cells. The finding raises questions about the promise of therapies that target cGAS-STING for immune modulation, researchers report today (January 24) in

Researchers at the University of Washington have discovered a novel DNA-sensing pathway that launches an antiviral response to foreign genetic material in human cells. Triggered by an enzyme called DNA protein kinase (DNA-PK), the newly found pathway is independent of the cGAS-STING pathway—until now considered the main regulator of mammalian innate immune responses to DNA—and is missing or inactive in mouse cells. The finding raises questions about the promise of therapies that target cGAS-STING for immune modulation, researchers report today (January 24) in  Wealth is power. An extreme concentration of wealth means an extreme concentration of power: the power to influence government policy, the power to stifle competition, the power to shape ideology. Together, these amount to the power to tilt the distribution of income to one’s advantage. This is the core reason why the extreme wealth of some can reduce what remains for the rest—why part of the income of today’s superrich can be earned at the expense of the rest of society. That’s what earned John Astor, Andrew Carnegie, John Rockefeller, and other Gilded Age industrialists their epithet of “Robber Barons.”

Wealth is power. An extreme concentration of wealth means an extreme concentration of power: the power to influence government policy, the power to stifle competition, the power to shape ideology. Together, these amount to the power to tilt the distribution of income to one’s advantage. This is the core reason why the extreme wealth of some can reduce what remains for the rest—why part of the income of today’s superrich can be earned at the expense of the rest of society. That’s what earned John Astor, Andrew Carnegie, John Rockefeller, and other Gilded Age industrialists their epithet of “Robber Barons.” Researchers at Cardiff University were analysing blood from a bank in Wales, looking for immune cells that could fight bacteria, when they found an entirely new type of T-cell.

Researchers at Cardiff University were analysing blood from a bank in Wales, looking for immune cells that could fight bacteria, when they found an entirely new type of T-cell. There are countless examples of past and present monstrous regimes in the real world. And they all raise the question of why people didn’t just rise up against their rulers. Some of us are quick to judge those who conform to such regimes as evil psychopaths – or at least morally inferior to ourselves.

There are countless examples of past and present monstrous regimes in the real world. And they all raise the question of why people didn’t just rise up against their rulers. Some of us are quick to judge those who conform to such regimes as evil psychopaths – or at least morally inferior to ourselves. As is apparent, Bonney’s work is not purely aesthetic or for its own sake; it’s not romantic or confessional in the sense of the personal divorced from the political, if such a thing is even possible. That’s not to suggest that his work is simple or accessible. In keeping with the British Poetry Revival of the 1960s and 1970s, in which poets rejected the prevailing conservatism of British literature, Bonney’s work is difficult, transgressive, subversive, and at times hermetic. “Don’t get me wrong,” Bonney writes in “Letter Against the Language,” “I’m not about to disappear into some kind of curate Cloud of Unknowing, or worse, some comfortably opaque experimental poetry. I mean, fuck that shit.” Our Death bears the imprints of such avant-garde movements as sound poetry, concrete poetry, visual poetry, and performance art. As a working-class boy from Brighton, Bonney was steadfastly leftist in his verse, though, as he noted in a recent interview with Jeffrey Grunthaner in BOMB, “I hate mainstream left wing artists. I don’t consider my work to be protest work. I’m not trying to convince anybody to not like capitalism. My ideal audience already hates cops.” Some of the best prophets aren’t there to make you do stuff; they exist to bear witness.

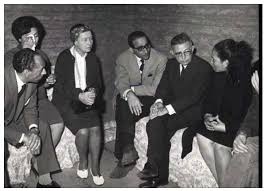

As is apparent, Bonney’s work is not purely aesthetic or for its own sake; it’s not romantic or confessional in the sense of the personal divorced from the political, if such a thing is even possible. That’s not to suggest that his work is simple or accessible. In keeping with the British Poetry Revival of the 1960s and 1970s, in which poets rejected the prevailing conservatism of British literature, Bonney’s work is difficult, transgressive, subversive, and at times hermetic. “Don’t get me wrong,” Bonney writes in “Letter Against the Language,” “I’m not about to disappear into some kind of curate Cloud of Unknowing, or worse, some comfortably opaque experimental poetry. I mean, fuck that shit.” Our Death bears the imprints of such avant-garde movements as sound poetry, concrete poetry, visual poetry, and performance art. As a working-class boy from Brighton, Bonney was steadfastly leftist in his verse, though, as he noted in a recent interview with Jeffrey Grunthaner in BOMB, “I hate mainstream left wing artists. I don’t consider my work to be protest work. I’m not trying to convince anybody to not like capitalism. My ideal audience already hates cops.” Some of the best prophets aren’t there to make you do stuff; they exist to bear witness. By the time that Sartre and de Beauvoir arrived in Tel Aviv, Israeli leaders and readers were wary of how Sartre would respond to Israel. In an interview with the Israeli newspaper Yediot Aharonot, Sartre affirmed Israel’s right to exist, but his support did not go beyond that affirmation. Clearly his sympathies were with the Palestinians – both with the refuges he met in Gaza and with the Palestinians living in the state of Israel as “Israeli Arabs.”

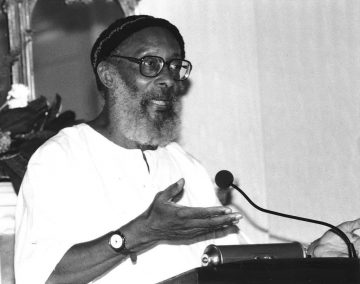

By the time that Sartre and de Beauvoir arrived in Tel Aviv, Israeli leaders and readers were wary of how Sartre would respond to Israel. In an interview with the Israeli newspaper Yediot Aharonot, Sartre affirmed Israel’s right to exist, but his support did not go beyond that affirmation. Clearly his sympathies were with the Palestinians – both with the refuges he met in Gaza and with the Palestinians living in the state of Israel as “Israeli Arabs.” The early notices of Kamau Brathwaite’s death yesterday emphasized the indisputable fact that he was a Caribbean and West Indian writer. The emphasis says something crucial about Brathwaite as a person and an artist. He wrote over thirty books of an astonishing variety and sophistication—history, anthropology, tracts and polemics, poetry and fiction (the poetry and fiction unique and radical in the way language and the technologies of language are understood and deployed). He ranged over three continents during his tremendous career. He went to college in England and studied with F. R. Leavis. He did not only live and work in Africa, he had an Africanist period in his thinking and took an African first name. He taught in New York. He never, though, separated himself from either his imaginative allegiance to the speech and culture of the English-speaking Caribbean or his physical allegiance to his birthplace, Barbados. The eulogies now pouring out of that island are rich with the kind of grief and pride that are triggered only by the loss of a beloved native son.

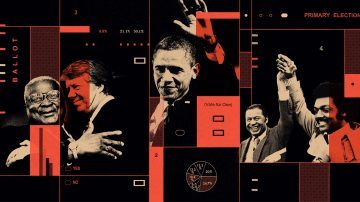

The early notices of Kamau Brathwaite’s death yesterday emphasized the indisputable fact that he was a Caribbean and West Indian writer. The emphasis says something crucial about Brathwaite as a person and an artist. He wrote over thirty books of an astonishing variety and sophistication—history, anthropology, tracts and polemics, poetry and fiction (the poetry and fiction unique and radical in the way language and the technologies of language are understood and deployed). He ranged over three continents during his tremendous career. He went to college in England and studied with F. R. Leavis. He did not only live and work in Africa, he had an Africanist period in his thinking and took an African first name. He taught in New York. He never, though, separated himself from either his imaginative allegiance to the speech and culture of the English-speaking Caribbean or his physical allegiance to his birthplace, Barbados. The eulogies now pouring out of that island are rich with the kind of grief and pride that are triggered only by the loss of a beloved native son. Not that long ago, they were just a slender fraction of the party, one kept at arm’s length by presidential candidates. But today, black voters have emerged as a muscular political force and one of the most intensely courted constituencies in Democratic politics. In 2020, they are likely to account for at least one out of every four ballots cast in the party’s presidential primaries, more than tripling — and perhaps even quadrupling — the share they accounted for just a few decades ago. It’s a political and demographic revolution over the course of 40 years that we are able to document here through exit polling, which major media organizations have been sponsoring on a wide scale in every Democratic presidential primary race since 1976. But until now, much of this data has been hard to come by, unavailable online, walled off in academic archives, even discarded by the news media outlets that sponsored it.

Not that long ago, they were just a slender fraction of the party, one kept at arm’s length by presidential candidates. But today, black voters have emerged as a muscular political force and one of the most intensely courted constituencies in Democratic politics. In 2020, they are likely to account for at least one out of every four ballots cast in the party’s presidential primaries, more than tripling — and perhaps even quadrupling — the share they accounted for just a few decades ago. It’s a political and demographic revolution over the course of 40 years that we are able to document here through exit polling, which major media organizations have been sponsoring on a wide scale in every Democratic presidential primary race since 1976. But until now, much of this data has been hard to come by, unavailable online, walled off in academic archives, even discarded by the news media outlets that sponsored it.