Rachel Love Nuwer in Undark:

The Florida Panther’s unlikely comeback is neatly summarized on the website of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. From around 20 surviving animals in the early 1970s (with the population possibly reaching as few as six), there are now more than 200 and counting. The agency credits this recovery to studious collaboration between federal and state officials, including the introduction of life-saving genetic diversity to the endangered panther population, as well as conservation of vital habitat.

The Florida Panther’s unlikely comeback is neatly summarized on the website of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. From around 20 surviving animals in the early 1970s (with the population possibly reaching as few as six), there are now more than 200 and counting. The agency credits this recovery to studious collaboration between federal and state officials, including the introduction of life-saving genetic diversity to the endangered panther population, as well as conservation of vital habitat.

What the official description doesn’t mention, however, is the drama, individual perseverance, and messy, sometimes blundering, realities that enabled the Florida panther to claw its way back from the precipice of extinction. For a full account of this swampy, fraught history, readers can instead turn to award-winning journalist Craig Pittman’s new book, “Cat Tale: The Wild, Weird Battle to Save the Florida Panther.”

More than a natural history monograph, “Cat Tale” is the story of Florida’s complicated relationship with its state animal.

More here.

Senate Republicans, by and large, have reached an unspoken consensus about President Trump and Ukraine. He should not have put a temporary freeze on congressionally authorized aid to Ukraine, should not have dabbled with using the aid to get Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden or a nutty theory about Ukrainian hacking during the 2016 election, and should not have kept defending his “perfect call” as such. At the same time, his conduct does not merit his removal from office — especially since voters will get to pass judgment on that conduct in a few months.

Senate Republicans, by and large, have reached an unspoken consensus about President Trump and Ukraine. He should not have put a temporary freeze on congressionally authorized aid to Ukraine, should not have dabbled with using the aid to get Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden or a nutty theory about Ukrainian hacking during the 2016 election, and should not have kept defending his “perfect call” as such. At the same time, his conduct does not merit his removal from office — especially since voters will get to pass judgment on that conduct in a few months.

THE BEAUTY

THE BEAUTY It’s always been fashionable to announce that what Sontag called ‘serious’ intellectual culture is dead or dying. Now, it’s supposed to be a result of what’s inaccurately referred to as ‘the algorithm’, but as Tolentino acknowledges, before she ploughs on with the analysis regardless, ‘people have been carping in this way for many centuries.’ What’s truly amazing about these times is that we have more access than ever before to material that demonstrates the continuity and repetitiveness of history, including evidence of the insistence by critics of all eras that this time is different, yet so many still buy into the pyramid scheme that we are special. It is both self-aggrandising and self-exonerating; it feels right. What seems self-evident to me is that public writing is always at least a little bit self-interested, demanding, controlling and delusional, and that it’s the writer’s responsibility to add enough of something else to tip the scales away from herself. For readers hoping to optimise the process of understanding their own lives, Tolentino’s book will seem ‘productive’. But those are her terms. No one has to accept

It’s always been fashionable to announce that what Sontag called ‘serious’ intellectual culture is dead or dying. Now, it’s supposed to be a result of what’s inaccurately referred to as ‘the algorithm’, but as Tolentino acknowledges, before she ploughs on with the analysis regardless, ‘people have been carping in this way for many centuries.’ What’s truly amazing about these times is that we have more access than ever before to material that demonstrates the continuity and repetitiveness of history, including evidence of the insistence by critics of all eras that this time is different, yet so many still buy into the pyramid scheme that we are special. It is both self-aggrandising and self-exonerating; it feels right. What seems self-evident to me is that public writing is always at least a little bit self-interested, demanding, controlling and delusional, and that it’s the writer’s responsibility to add enough of something else to tip the scales away from herself. For readers hoping to optimise the process of understanding their own lives, Tolentino’s book will seem ‘productive’. But those are her terms. No one has to accept In the summer of 1922 two men called George took part in the first attempted ascent of Mount Everest. George Mallory was an establishment man. A Cambridge graduate and son of a Church of England rector, he dressed in the respectable climbing gear of the time, a jacket and tough, cotton plus-fours. George Finch, his fellow explorer, was an outsider, a moustachioed Australian with chiselled good looks and an independent streak who liked experimenting with new contraptions: he took bottled oxygen to use at high altitude, and wore a specially commissioned coat made from bright green hot-air balloon fabric stuffed with the down of eider ducks. Though climbers were already using sleeping bags filled with down, Finch’s fellow climbers initially mocked his bulky coat. That changed as they approached Everest. “Today has been bitterly cold with a gale of a wind to liven things up,” Finch wrote in his diary. “Everybody now envies my eiderdown coat and it is no longer laughed at.” The two Georges turned back after their third failed attempt on the summit. Two years later Mallory joined another expedition to Everest, but went missing close to the top; his climbing feats were then romanticised by a hero-hungry public. Finch never tried again and pursued a considerably less romantic career as a chemistry professor. Yet ultimately he had a greater impact than that of the better-known George. Today, climbers at high altitude routinely carry oxygen. His other innovation has been even more influential, extending far beyond mountaineering circles: on the 1922 expedition George Finch invented the puffer jacket.

In the summer of 1922 two men called George took part in the first attempted ascent of Mount Everest. George Mallory was an establishment man. A Cambridge graduate and son of a Church of England rector, he dressed in the respectable climbing gear of the time, a jacket and tough, cotton plus-fours. George Finch, his fellow explorer, was an outsider, a moustachioed Australian with chiselled good looks and an independent streak who liked experimenting with new contraptions: he took bottled oxygen to use at high altitude, and wore a specially commissioned coat made from bright green hot-air balloon fabric stuffed with the down of eider ducks. Though climbers were already using sleeping bags filled with down, Finch’s fellow climbers initially mocked his bulky coat. That changed as they approached Everest. “Today has been bitterly cold with a gale of a wind to liven things up,” Finch wrote in his diary. “Everybody now envies my eiderdown coat and it is no longer laughed at.” The two Georges turned back after their third failed attempt on the summit. Two years later Mallory joined another expedition to Everest, but went missing close to the top; his climbing feats were then romanticised by a hero-hungry public. Finch never tried again and pursued a considerably less romantic career as a chemistry professor. Yet ultimately he had a greater impact than that of the better-known George. Today, climbers at high altitude routinely carry oxygen. His other innovation has been even more influential, extending far beyond mountaineering circles: on the 1922 expedition George Finch invented the puffer jacket. The Italian Renaissance humanist Girolamo Fracastoro is best remembered for his

The Italian Renaissance humanist Girolamo Fracastoro is best remembered for his

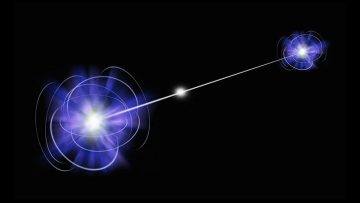

Albert Einstein famously said that quantum mechanics should allow two objects to affect each other’s behaviour instantly across vast distances, something he

Albert Einstein famously said that quantum mechanics should allow two objects to affect each other’s behaviour instantly across vast distances, something he  In September 2009, over 3,000 bee enthusiasts from around the world descended on the city of Montpellier in southern France for Apimondia — a festive beekeeper conference filled with scientific lectures, hobbyist demonstrations, and commercial beekeepers hawking honey. But that year, a cloud loomed over the event: bee colonies across the globe were collapsing, and billions of bees were dying.

In September 2009, over 3,000 bee enthusiasts from around the world descended on the city of Montpellier in southern France for Apimondia — a festive beekeeper conference filled with scientific lectures, hobbyist demonstrations, and commercial beekeepers hawking honey. But that year, a cloud loomed over the event: bee colonies across the globe were collapsing, and billions of bees were dying. Serotonin is a story of psychic descent and personal disintegration, with a bloody political interlude grafted between its narrator’s initial crack-up and his terminal plunge. Florent-Claude Labrouste is forty-six years old and a veteran of the revolving door between the public and private French agricultural bureaucracies. His life has reached an erotic dead end. He’s a good-looking man, so he tells us, but it is a false front: “I have demonstrated my inability to take control of my life, the virility that seemed to emanate from my square face with its clear angles and chiselled features is in truth nothing but a decoy, a trick pure and simple—for which, it is true, I was not responsible.” He’s had a string of girlfriends, makes a good living, rents a big Paris flat, owns a vacation home in Spain, and has a substantial inheritance from his deceased parents, who were the opposite of abusive. And yet . . .

Serotonin is a story of psychic descent and personal disintegration, with a bloody political interlude grafted between its narrator’s initial crack-up and his terminal plunge. Florent-Claude Labrouste is forty-six years old and a veteran of the revolving door between the public and private French agricultural bureaucracies. His life has reached an erotic dead end. He’s a good-looking man, so he tells us, but it is a false front: “I have demonstrated my inability to take control of my life, the virility that seemed to emanate from my square face with its clear angles and chiselled features is in truth nothing but a decoy, a trick pure and simple—for which, it is true, I was not responsible.” He’s had a string of girlfriends, makes a good living, rents a big Paris flat, owns a vacation home in Spain, and has a substantial inheritance from his deceased parents, who were the opposite of abusive. And yet . . . Understood as a military struggle, slavery was a conflict staggering in its scale, even just in the Caribbean. Beginning in the seventeenth century, European traders prowled Africa’s Gold Coast looking to exchange guns, textiles, or even a bottle of brandy for able bodies; by the middle of the eighteenth century, slaves constituted ninety per cent of Europe’s trade with Africa. Of the more than ten million Africans who survived the journey across the Atlantic, six hundred thousand went to work in Jamaica, an island roughly the size of Connecticut. By contrast, four hundred thousand were sent to all of North America. (The domestic slave trade was another matter: by the time the Civil War began, there were roughly four million enslaved people living in the United States.)

Understood as a military struggle, slavery was a conflict staggering in its scale, even just in the Caribbean. Beginning in the seventeenth century, European traders prowled Africa’s Gold Coast looking to exchange guns, textiles, or even a bottle of brandy for able bodies; by the middle of the eighteenth century, slaves constituted ninety per cent of Europe’s trade with Africa. Of the more than ten million Africans who survived the journey across the Atlantic, six hundred thousand went to work in Jamaica, an island roughly the size of Connecticut. By contrast, four hundred thousand were sent to all of North America. (The domestic slave trade was another matter: by the time the Civil War began, there were roughly four million enslaved people living in the United States.) The Death of Jesus abounds in definitional disputes, hairline distinctions and logical paradoxes. When David needs a transfusion, there is dispute over whether blood is best understood by science or primal instinct; Dmitri thinks that the doctor’s “types” are less important than a donor’s personal affinity with the patient. Simón shifts the goalposts on whether David should be treated as “an exception”, depending on what kind of treatment (medical, pedagogical) he is requesting. David dismisses the legitimacy of the word “why” when he isn’t the one using it and insists that things “don’t have to be true to be true”. And towards the end, the reader is prompted to wonder if David’s end isn’t really a beginning? There’s a rumour that on dying you “wake up on some foreign shore” – as Simón and David did at the start of the first volume – and are forced “to play out the rigmarole all over again”.

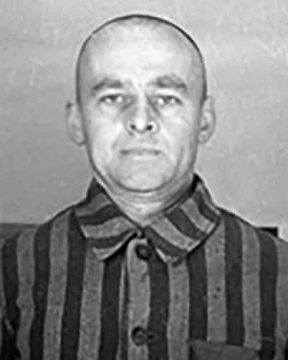

The Death of Jesus abounds in definitional disputes, hairline distinctions and logical paradoxes. When David needs a transfusion, there is dispute over whether blood is best understood by science or primal instinct; Dmitri thinks that the doctor’s “types” are less important than a donor’s personal affinity with the patient. Simón shifts the goalposts on whether David should be treated as “an exception”, depending on what kind of treatment (medical, pedagogical) he is requesting. David dismisses the legitimacy of the word “why” when he isn’t the one using it and insists that things “don’t have to be true to be true”. And towards the end, the reader is prompted to wonder if David’s end isn’t really a beginning? There’s a rumour that on dying you “wake up on some foreign shore” – as Simón and David did at the start of the first volume – and are forced “to play out the rigmarole all over again”. Just after Witold Pilecki’s arrival at

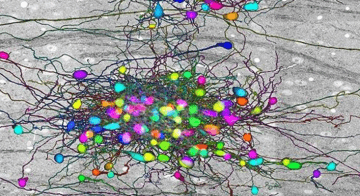

Just after Witold Pilecki’s arrival at  On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement. Printed on paper, the dataset would fill 116 billion pages, double-spaced. When I recently finished writing the story of my data, the magnum opus fit on fewer than two dozen printed pages. Performing the experiments turned out to be the easy part. I had spent the last year agonizing over the data, observing and asking questions. The answers left out large chunks that did not pertain to the questions, like a map leaves out irrelevant details of a territory. But, as massive as my dataset sounds, it represents just a tiny chunk of a dataset taken from the whole brain. And the questions it asks—Do neurons in the visual cortex do anything when an animal can’t see? What happens when inputs to the visual cortex from other brain regions are shut off?—are small compared to the ultimate question in neuroscience: How does the brain work?

On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement. Printed on paper, the dataset would fill 116 billion pages, double-spaced. When I recently finished writing the story of my data, the magnum opus fit on fewer than two dozen printed pages. Performing the experiments turned out to be the easy part. I had spent the last year agonizing over the data, observing and asking questions. The answers left out large chunks that did not pertain to the questions, like a map leaves out irrelevant details of a territory. But, as massive as my dataset sounds, it represents just a tiny chunk of a dataset taken from the whole brain. And the questions it asks—Do neurons in the visual cortex do anything when an animal can’t see? What happens when inputs to the visual cortex from other brain regions are shut off?—are small compared to the ultimate question in neuroscience: How does the brain work? I have a confession to make: I thought it distinctly odd that Norton asked me to translate The Art of War. Perhaps I am too used to gender stereotypes, but like many women who came of age during the Vietnam War, I shy away from violence (verbal and physical) and regard myself as a near-pacifist. Unsurprisingly, I associated the Chinese Art of War with “Kill, kill, kill,” since my first awareness of the text’s existence came during the early 1970s, soon after Brigadier General Griffith introduced his translation as a way to “know thy enemy.”

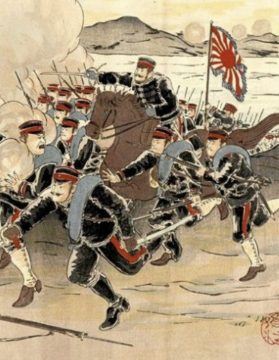

I have a confession to make: I thought it distinctly odd that Norton asked me to translate The Art of War. Perhaps I am too used to gender stereotypes, but like many women who came of age during the Vietnam War, I shy away from violence (verbal and physical) and regard myself as a near-pacifist. Unsurprisingly, I associated the Chinese Art of War with “Kill, kill, kill,” since my first awareness of the text’s existence came during the early 1970s, soon after Brigadier General Griffith introduced his translation as a way to “know thy enemy.”