Christian Sorace in The Ideas Letter:

Current political discourse is haunted by a specter—the specter of Maoism. When conventional politics starts to spin away from the mainstream and arouses the passions of the people, Mao often is invoked. Commentators routinely analogize Trump to him, calling the two men kindred spirits in “chaos” who “would have got on well.” The China expert Orville Schell has written that the Chairman “must be looking down from his Marxist-Leninist heaven with a smile.”

But would Mao really have celebrated anything beyond disorder for the US empire?

Such easy analogies are not only incorrect; worse, they damage our capacity for critical thinking and political action. Relying on them inhibits imagining a democratic politics beyond liberal democracy.

During periods of uncertainty, historical analogies can convey familiarity. But as they do, they distract from what is new in the present. Trump has been compared not only to Mao, but also to Hitler—as well as to contemporaries such as Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and the dictators of so-called banana republics. As we travel in that time machine, one moment we are in the kinetic interwar years; in the next, we glaciate in a new Cold War. Analogies seem to reassure us that we have been there before. In fact, they only confuse any real sense of where we are now.

Portraits of bad men—master manipulators with a sociopathic disregard for the havoc they wreak on their nations, peoples, and economies—may be accurate characterizations, but they say little about sociopolitical dynamics, which are larger than any personality. They do not make up for proper political analysis. When a leader’s actions are presented out of context, their only imaginable purpose appears to be the consolidation of power—power without politics.

Yet historical analogies themselves are rhetorical devices; they too are tellers and makers of tales, and they create political claims. They implicitly ask us to see the world in a certain way—usually from the perspective of the status quo, from which alternative modes of politics are passed over or pathologized. To compare Trump to Mao and the US culture wars to the Cultural Revolution is to reduce entirely different political visions to reified personalities.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The comparison with 1979 is lazy because it assumes that history is a model that repeats itself in exactly the same way. So when the bazaaris protested and closed their shops in late December, many “Iran-watchers” perked up, suggesting that this moment would result in an overthrow of the state. In fact, whenever there’s turmoil in Iran people reach for the 1979 analogy, a move that narrows our political imagination and stunts our analytical capacities.

The comparison with 1979 is lazy because it assumes that history is a model that repeats itself in exactly the same way. So when the bazaaris protested and closed their shops in late December, many “Iran-watchers” perked up, suggesting that this moment would result in an overthrow of the state. In fact, whenever there’s turmoil in Iran people reach for the 1979 analogy, a move that narrows our political imagination and stunts our analytical capacities.

The Peloponnesian War ended in 404 BCE with Athens’s devastating loss. Its once heralded naval fleet was largely destroyed. Plague and defeat on the battlefield had killed more than a quarter of its people. Conflicts and epidemics had left the Athenian economy in shambles. Restoring prosperity required lasting peace, but asking the proud Athenians to lay down swords after humiliation was a political gamble. They needed a more straightforward approach to ending aggression.

The Peloponnesian War ended in 404 BCE with Athens’s devastating loss. Its once heralded naval fleet was largely destroyed. Plague and defeat on the battlefield had killed more than a quarter of its people. Conflicts and epidemics had left the Athenian economy in shambles. Restoring prosperity required lasting peace, but asking the proud Athenians to lay down swords after humiliation was a political gamble. They needed a more straightforward approach to ending aggression. Halfway through

Halfway through  V

V In the original clinical trials of

In the original clinical trials of  I

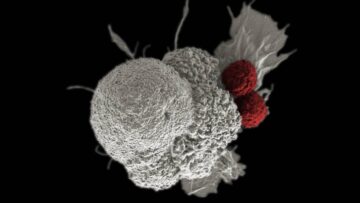

I Lights, vitamin, action. A combination of vitamin B2 and ultraviolet light hardly sounds like a next-generation cancer treatment. But

Lights, vitamin, action. A combination of vitamin B2 and ultraviolet light hardly sounds like a next-generation cancer treatment. But  It was just the type of document I was hoping to find.

It was just the type of document I was hoping to find. It’s often been observed that taking full advantage of AI will require changing work practices, just as taking full advantage of electric motors in manufacturing required changing the way factories were laid out. But what will those changes look like? Early answers are starting to emerge, coming (unsurprisingly) from the field of software development. Interestingly, the biggest impacts may not be cost savings!

It’s often been observed that taking full advantage of AI will require changing work practices, just as taking full advantage of electric motors in manufacturing required changing the way factories were laid out. But what will those changes look like? Early answers are starting to emerge, coming (unsurprisingly) from the field of software development. Interestingly, the biggest impacts may not be cost savings! S.N.S. Sastry’s 1967 documentary film I Am 20 opens with the whistle of a train and the words of T. N. Subramanian, a loquacious young man with a book of chemistry in front. In a nearly 20-minute film documenting the reflections, hopes, and fears of 20-year-old Indians regarding the equally old Indian republic, Subramanian begins with confessing his ambition, much like Mohandas Gandhi who had returned from South Africa, to “go through this country top to bottom” with “a pad and paper, a tape recorder, and a camera… seeing all kinds of people… their anguish and their anger, the fertile soil, the pastures, everything! So that one day when I could come back, I could open the book and remind myself of what I am part of and what is part of me.”

S.N.S. Sastry’s 1967 documentary film I Am 20 opens with the whistle of a train and the words of T. N. Subramanian, a loquacious young man with a book of chemistry in front. In a nearly 20-minute film documenting the reflections, hopes, and fears of 20-year-old Indians regarding the equally old Indian republic, Subramanian begins with confessing his ambition, much like Mohandas Gandhi who had returned from South Africa, to “go through this country top to bottom” with “a pad and paper, a tape recorder, and a camera… seeing all kinds of people… their anguish and their anger, the fertile soil, the pastures, everything! So that one day when I could come back, I could open the book and remind myself of what I am part of and what is part of me.”