James Meyer at Artforum:

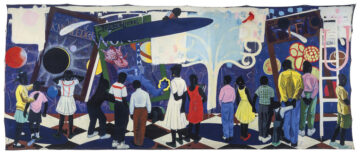

The artist’s astounding success was by no means predictable when he started out. History painting, the highest of the classical painterly genres as defined by the Royal Academy’s founders, was a distant memory by the 1980s, when the revival of figurative painting and tired Expressionist formulas on both sides of the Atlantic inspired the passionate critiques of Benjamin H. D. Buchloh and his October compatriots. In his well-argued catalogue essay, Godfrey reckons with his own earlier skepticism of figuration, including Marshall’s. As he describes, a visit to the painter’s Chicago studio in 2012 instigated a process of internal interrogation. He came to believe that history painting—if refreshed by new techniques—would speak more directly to audiences, including viewers not typically drawn to museums, than the conceptualist formulas of a prior generation, embracing a position he ascribes to Marshall himself: “As [Marshall] knew, figurative paintings in museums attracted a large audience of experts, first-timers, tourists and schoolchildren, far broader than the niche audience for the lens- and text-based artworks I revered then.” The crowds of teenagers and children listening raptly to the lectures of identical-looking docents in the back-to-back galleries in Untitled (Underpainting), 2018, imagine an art world infinitely more inclusive than the one Marshall entered as a young artist.

The artist’s astounding success was by no means predictable when he started out. History painting, the highest of the classical painterly genres as defined by the Royal Academy’s founders, was a distant memory by the 1980s, when the revival of figurative painting and tired Expressionist formulas on both sides of the Atlantic inspired the passionate critiques of Benjamin H. D. Buchloh and his October compatriots. In his well-argued catalogue essay, Godfrey reckons with his own earlier skepticism of figuration, including Marshall’s. As he describes, a visit to the painter’s Chicago studio in 2012 instigated a process of internal interrogation. He came to believe that history painting—if refreshed by new techniques—would speak more directly to audiences, including viewers not typically drawn to museums, than the conceptualist formulas of a prior generation, embracing a position he ascribes to Marshall himself: “As [Marshall] knew, figurative paintings in museums attracted a large audience of experts, first-timers, tourists and schoolchildren, far broader than the niche audience for the lens- and text-based artworks I revered then.” The crowds of teenagers and children listening raptly to the lectures of identical-looking docents in the back-to-back galleries in Untitled (Underpainting), 2018, imagine an art world infinitely more inclusive than the one Marshall entered as a young artist.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

JOHN MARTIN NEVER smoked cigarettes. He did not use drugs or drink alcohol. Martin’s vice was book collecting, which he began in earnest in the late 1930s after he dropped out of UCLA. His enrollment was brief: he left when he discovered that his favorite modern authors, such as Ezra Pound, D. H. Lawrence, and Wallace Stevens, were not on the curriculum.

JOHN MARTIN NEVER smoked cigarettes. He did not use drugs or drink alcohol. Martin’s vice was book collecting, which he began in earnest in the late 1930s after he dropped out of UCLA. His enrollment was brief: he left when he discovered that his favorite modern authors, such as Ezra Pound, D. H. Lawrence, and Wallace Stevens, were not on the curriculum. Cells change constantly. Researchers tend to study their dynamics in two ways. One method is to watch them live under a microscope, where a limited number of types of molecules can be tracked for days with fluorescent tags. Another way is in test tubes at a single time point, usually the end of an experiment, where mRNA molecules can be measured and compared with those in other cells

Cells change constantly. Researchers tend to study their dynamics in two ways. One method is to watch them live under a microscope, where a limited number of types of molecules can be tracked for days with fluorescent tags. Another way is in test tubes at a single time point, usually the end of an experiment, where mRNA molecules can be measured and compared with those in other cells  Who are you? What’s going on deep inside yourself? How do you understand your own mind? The ancient sages had big debates about this, and now modern neuroscience is helping us sort it all out. When my amateur fascination with neuroscience began, roughly two decades ago, the scientists seemed to spend a lot of time trying to figure out where in the brain different functions were happening. That led to a lot of simplistic shorthand in the popular conversation: Emotion is in the amygdala. Motivation is in the nucleus accumbens. Back in those days management consultants could make a good living by giving presentations with slides of brain scans while uttering sentences like: “You can see that the parietal lobe is all lit up. This proves that …”

Who are you? What’s going on deep inside yourself? How do you understand your own mind? The ancient sages had big debates about this, and now modern neuroscience is helping us sort it all out. When my amateur fascination with neuroscience began, roughly two decades ago, the scientists seemed to spend a lot of time trying to figure out where in the brain different functions were happening. That led to a lot of simplistic shorthand in the popular conversation: Emotion is in the amygdala. Motivation is in the nucleus accumbens. Back in those days management consultants could make a good living by giving presentations with slides of brain scans while uttering sentences like: “You can see that the parietal lobe is all lit up. This proves that …” A few days after my brother died, I sat in the living room of a dead house and made eye contact with a bird.

A few days after my brother died, I sat in the living room of a dead house and made eye contact with a bird. What we’re building today is not “an AI” that might cooperate or rebel, but an expanding capacity to design, develop, produce, deploy, and adapt complex systems at scale—the basis for a hypercapable world. Taking this prospect seriously changes what to expect and what we can do.

What we’re building today is not “an AI” that might cooperate or rebel, but an expanding capacity to design, develop, produce, deploy, and adapt complex systems at scale—the basis for a hypercapable world. Taking this prospect seriously changes what to expect and what we can do. When Katherine Dunn

When Katherine Dunn Unlike earlier protest waves, this unrest unfolds as Iran’s core pillars—its economic viability, coercive capacity, and external deterrence—fail simultaneously, creating a systemic crisis the regime has never faced and may not survive.

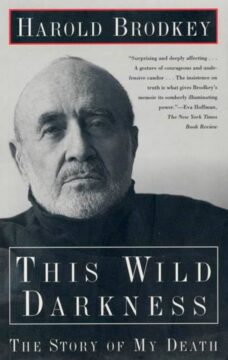

Unlike earlier protest waves, this unrest unfolds as Iran’s core pillars—its economic viability, coercive capacity, and external deterrence—fail simultaneously, creating a systemic crisis the regime has never faced and may not survive. What conditions did Brodkey observe? That already in 1992, “the old American middle class is gone,” its scattered remaining members defined only by participation in such institutions as the stock market, the tax system and “an interlocking web of universities.” Most of them live in isolated suburbs, which “do not and cannot do much to preserve culture or the interplay of groups and classes that heretofore made up American education in politics, in American political realities.” Due to the consequent loss of “political and social ballast,” awareness of local reality has given way to the seductiveness of mass fantasy. “Moral issues are complex and tangled. The jury system argues tacitly that all issues are arguable. And they are. And that time changes things. And it does. That adjudication and rights and duties are complex matters.” Common sense, but also “almost all culture, literature, history, philosophy, even religion, if studied and pondered, tell us that. The disappearance of common sense and the ebbing of culture and the advance of the dreamed-of and dreamlike are clear signs of social danger.”

What conditions did Brodkey observe? That already in 1992, “the old American middle class is gone,” its scattered remaining members defined only by participation in such institutions as the stock market, the tax system and “an interlocking web of universities.” Most of them live in isolated suburbs, which “do not and cannot do much to preserve culture or the interplay of groups and classes that heretofore made up American education in politics, in American political realities.” Due to the consequent loss of “political and social ballast,” awareness of local reality has given way to the seductiveness of mass fantasy. “Moral issues are complex and tangled. The jury system argues tacitly that all issues are arguable. And they are. And that time changes things. And it does. That adjudication and rights and duties are complex matters.” Common sense, but also “almost all culture, literature, history, philosophy, even religion, if studied and pondered, tell us that. The disappearance of common sense and the ebbing of culture and the advance of the dreamed-of and dreamlike are clear signs of social danger.” If you read a book

If you read a book In the early 1990s, a groundswell of young women raised on second-wave feminism but marginalized within the supposedly progressive realm of punk music rose up to make themselves heard, in a movement known as riot grrrl. Bands like

In the early 1990s, a groundswell of young women raised on second-wave feminism but marginalized within the supposedly progressive realm of punk music rose up to make themselves heard, in a movement known as riot grrrl. Bands like  Dr. Franz Kafka, as he is officially listed, is buried in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery, about a mile down the road from where I live in the neighbourhood of Žižkov. The greater Olšany Cemetery, which it adjoins, is across the street from my apartment. I often go there for walks in the evening, meandering along its overgrown rows and flower-crowded graves. Kafka’s headstone looks like an expressionist prism, a long diamond slightly fattened at its top. The stone bed in front of it is frequently littered with candles, pens, scraps of paper, rocks painted with pictures of beetles. He is interred there along with his mother Julie and his father Hermann (whom he is unable to escape even in death). Max Brod, without whom we’d know nothing of Kafka, has a plaque on the opposite wall. Given that Kafka instructed Brod to burn all of his work “unread,” he almost certainly would not have welcomed people flocking to his grave, so whenever I stop by to say hello to him, I think to myself: “He would hate this.”

Dr. Franz Kafka, as he is officially listed, is buried in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery, about a mile down the road from where I live in the neighbourhood of Žižkov. The greater Olšany Cemetery, which it adjoins, is across the street from my apartment. I often go there for walks in the evening, meandering along its overgrown rows and flower-crowded graves. Kafka’s headstone looks like an expressionist prism, a long diamond slightly fattened at its top. The stone bed in front of it is frequently littered with candles, pens, scraps of paper, rocks painted with pictures of beetles. He is interred there along with his mother Julie and his father Hermann (whom he is unable to escape even in death). Max Brod, without whom we’d know nothing of Kafka, has a plaque on the opposite wall. Given that Kafka instructed Brod to burn all of his work “unread,” he almost certainly would not have welcomed people flocking to his grave, so whenever I stop by to say hello to him, I think to myself: “He would hate this.” T

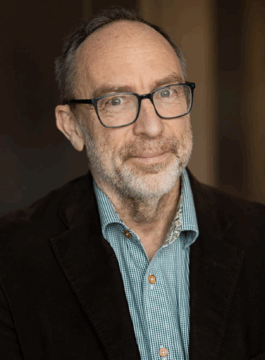

T Jimmy Wales, an Internet entrepreneur from Huntsville, Alabama, now based in London, is best known for creating Wikipedia, which launched in January 2001. The online encyclopedia now holds more than seven million articles and has become a standard guide for anyone seeking information.

Jimmy Wales, an Internet entrepreneur from Huntsville, Alabama, now based in London, is best known for creating Wikipedia, which launched in January 2001. The online encyclopedia now holds more than seven million articles and has become a standard guide for anyone seeking information.