Jerry Saltz at New York Magazine:

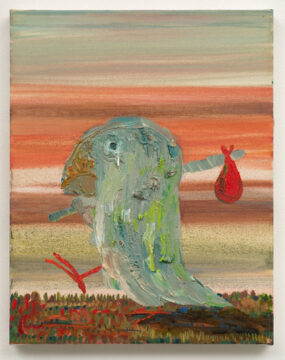

Eisenman has said she started out in a “degenerate and proto-queer” environment, asserting that, when she arrived in New York in the late 1980s, there “was no such thing as queer yet.” The artist wasn’t interested in modernism’s pieties. She was after drama. Her influences include Caravaggio, Giotto, Michelangelo, Grant Wood, Georg Baselitz, and WPA murals, all mixed into clusterfucks of seriousness and stupidity, tenderness and the grotesquerie. Her Alice in Wonderland depicts a tiny Alice whose head is jammed into the vagina of Wonder Woman. She’s created scenes of castration and Betty Rubble and Wilma Flintstone in flagrante ecstasy. Artist Amy Sillman wrote that Eisenman renders figures “with riotous unpredictability, anti-Puritanically taking delight in misbehavior on every level.” Eisenman takes the sacred and drags it across the barroom floor.

Eisenman has said she started out in a “degenerate and proto-queer” environment, asserting that, when she arrived in New York in the late 1980s, there “was no such thing as queer yet.” The artist wasn’t interested in modernism’s pieties. She was after drama. Her influences include Caravaggio, Giotto, Michelangelo, Grant Wood, Georg Baselitz, and WPA murals, all mixed into clusterfucks of seriousness and stupidity, tenderness and the grotesquerie. Her Alice in Wonderland depicts a tiny Alice whose head is jammed into the vagina of Wonder Woman. She’s created scenes of castration and Betty Rubble and Wilma Flintstone in flagrante ecstasy. Artist Amy Sillman wrote that Eisenman renders figures “with riotous unpredictability, anti-Puritanically taking delight in misbehavior on every level.” Eisenman takes the sacred and drags it across the barroom floor.

Her paintings at 52 Walker are delirious indictments of politics, art, and money. The show is brilliantly installed on tinted Homasote walls that exude warmth and knit together the entire space. Drawings and collages are pushpinned to the walls.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

During a week in December when violence seemed to rap on every door, I saw two plays about women who take their lives into their own hands: Hedda Gabler at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, and Anna Christie at Saint Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The plays were written thirty years apart. Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen in 1891, and Anna Christie by Eugene O’Neill in 1921. That year, Alexander Woollcott, reviewing the first production of Anna Christie for the New York Times, wrote, “All grown-up playgoers should jot down in their notebooks the name of Anna Christie as that of a play they really ought to see.” Though O’Neill won the Pulitzer Prize for Anna Christie, the play has been infrequently performed. It is being directed now by Thomas Kail, and Anna is played by his wife, Michelle Williams. On the other hand, Hedda Gabler, directed this time by James Bundy and starring Marianna Gailus, is a warhorse.

During a week in December when violence seemed to rap on every door, I saw two plays about women who take their lives into their own hands: Hedda Gabler at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, and Anna Christie at Saint Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The plays were written thirty years apart. Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen in 1891, and Anna Christie by Eugene O’Neill in 1921. That year, Alexander Woollcott, reviewing the first production of Anna Christie for the New York Times, wrote, “All grown-up playgoers should jot down in their notebooks the name of Anna Christie as that of a play they really ought to see.” Though O’Neill won the Pulitzer Prize for Anna Christie, the play has been infrequently performed. It is being directed now by Thomas Kail, and Anna is played by his wife, Michelle Williams. On the other hand, Hedda Gabler, directed this time by James Bundy and starring Marianna Gailus, is a warhorse. An octopus’s adaptive camouflage has long inspired materials scientists looking to come up with new cloaking technologies. Now researchers have created a

An octopus’s adaptive camouflage has long inspired materials scientists looking to come up with new cloaking technologies. Now researchers have created a  T

T We often hear talk of things being good for our microbiome, and in turn, good for our

We often hear talk of things being good for our microbiome, and in turn, good for our  An awe-inspiring protest movement is shaking the foundations of power in Iran. Millions of people have taken to the streets to protest the corruption which has impoverished them, and the theocratic restrictions which have taken away their liberties. Men and especially women are standing up for their dignity and their livelihoods in the face of the deadly threat of state-sanctioned violence.

An awe-inspiring protest movement is shaking the foundations of power in Iran. Millions of people have taken to the streets to protest the corruption which has impoverished them, and the theocratic restrictions which have taken away their liberties. Men and especially women are standing up for their dignity and their livelihoods in the face of the deadly threat of state-sanctioned violence. Editor:

Editor: The unsettling operation of worms is something science realized a long time ago. Drawing on observations by Charles Darwin and Otto August Mangold, Jakob von Uexküll

The unsettling operation of worms is something science realized a long time ago. Drawing on observations by Charles Darwin and Otto August Mangold, Jakob von Uexküll  LAS VEGAS — Just beyond the flashing slot machines and cigarette-saturated casino air, thousands of the health obsessed gathered in a convention hall here to demonstrate their hacks for living longer lives. They infused ozone into their blood streams, stood on vibrating mats, swallowed samples of supplements and took scans of their livers.

LAS VEGAS — Just beyond the flashing slot machines and cigarette-saturated casino air, thousands of the health obsessed gathered in a convention hall here to demonstrate their hacks for living longer lives. They infused ozone into their blood streams, stood on vibrating mats, swallowed samples of supplements and took scans of their livers. In recent years, the vagus nerve has become an object of fascination, especially on social media. The vagal nerve fibers, which run from the brain to the abdomen, have been anointed by some influencers as the key to reducing anxiety, regulating the nervous system and helping the body to relax.

In recent years, the vagus nerve has become an object of fascination, especially on social media. The vagal nerve fibers, which run from the brain to the abdomen, have been anointed by some influencers as the key to reducing anxiety, regulating the nervous system and helping the body to relax. I had a book come out last July. It was about a dead poet and it led to many speaking engagements (be careful what you wish for). Nearly every weekend during the fall semester of 2025, I was on the road or in the air. Once, on the water.

I had a book come out last July. It was about a dead poet and it led to many speaking engagements (be careful what you wish for). Nearly every weekend during the fall semester of 2025, I was on the road or in the air. Once, on the water. I opened Claude Code and gave it the command: “Develop a web-based or software-based startup idea that will make me $1000 a month where you do all the work by generating the idea and implementing it. i shouldn’t have to do anything at all except run some program you give me once. it shouldn’t require any coding knowledge on my part, so make sure everything works well.” The AI asked me three multiple choice questions and decided that I should be selling sets of 500 prompts for professional users for $39. Without any further input, it then worked independently… FOR AN HOUR AND FOURTEEN MINUTES creating hundreds of code files and prompts. And then it gave me a single file to run that created and deployed a working website (filled with very sketchy fake marketing claims) that sold the promised 500 prompt set.

I opened Claude Code and gave it the command: “Develop a web-based or software-based startup idea that will make me $1000 a month where you do all the work by generating the idea and implementing it. i shouldn’t have to do anything at all except run some program you give me once. it shouldn’t require any coding knowledge on my part, so make sure everything works well.” The AI asked me three multiple choice questions and decided that I should be selling sets of 500 prompts for professional users for $39. Without any further input, it then worked independently… FOR AN HOUR AND FOURTEEN MINUTES creating hundreds of code files and prompts. And then it gave me a single file to run that created and deployed a working website (filled with very sketchy fake marketing claims) that sold the promised 500 prompt set.  It’s been twenty years since your exhibition at La Maison Rouge. That was my first encounter with your work and it also marked a radical turning-point for the photographer you were at the time. How do you see that exhibition today?

It’s been twenty years since your exhibition at La Maison Rouge. That was my first encounter with your work and it also marked a radical turning-point for the photographer you were at the time. How do you see that exhibition today?